Introduction

The history of Bengali theatre is rich, pregnant with its copious heritage. The beginning of the Bengali theatre can be traced to the construction of the Kolkata theatre back in the year 1779. However, nothing remarkable happened till the end of 1794. The year was 1795 and it was for the very first time the then intelligentsias of Kolkata witnessed Bengali theatre as the Russian dramatist Horasim Lebedev along with a Bengali theatre connoisseur Goloknath Das staged the Bengali translations of two English comedies, "Disguise" and "Love is the best doctor" in Kolkata. That was the time since when Bengali theatre started its journey. With few unstable steps and later with long strides it was with time, Bengali theatre gained a redefined dimension. By the year 1831 Bengali theatre became a whole new art form to mirror the then Bengal amidst its artistry.

The history of Bengali theatre is rich, pregnant with its copious heritage. The beginning of the Bengali theatre can be traced to the construction of the Kolkata theatre back in the year 1779. However, nothing remarkable happened till the end of 1794. The year was 1795 and it was for the very first time the then intelligentsias of Kolkata witnessed Bengali theatre as the Russian dramatist Horasim Lebedev along with a Bengali theatre connoisseur Goloknath Das staged the Bengali translations of two English comedies, "Disguise" and "Love is the best doctor" in Kolkata. That was the time since when Bengali theatre started its journey. With few unstable steps and later with long strides it was with time, Bengali theatre gained a redefined dimension. By the year 1831 Bengali theatre became a whole new art form to mirror the then Bengal amidst its artistry.

It is with the establishment of "Hindu Rangamanch" at Kolkata by Prasanna Kumar Thakur further supported Bengali theatre to take that steady step towards maturity. Prasanna Kumar staged Wilson`s English translation of Bhavabhuti`s Sanskrit Language drama "Uttar Ramacharitam" whilst laying the foundation for modern theatre in India. The history of Bengali theatre then gained a new diction. Other important attempts in developing Bengali theatre in the then Bengal include Nabin Basu`s Jorasanko Natyashala, the private stages of Ashutosh Deb and Ramjay Basak , Vidyotsahini Mancha , Metropolitan Theatre , Shobhabazar Private Theatrical Society and most importantly the Bagbazar Amateur Theatre.

Bengali theatre, which was already rich as an art form by then, became a vehicle of mass education, an effort in reflecting the then society. Bengali theatre again in the 19th century witnessed a colossal change as the rich, young Bengalis of Kolkata started to write plays based on British realistic manikins whilst ideally weaving them with Indian songs, classical dance and music to add that little extra. Rabindranath Tagore`s Raktakarabi (Red Oleanders) and Raja (The King of the Dark Chamber) became an important part of this effort. At that time the works of William Shakespeare were also widely translated and adapted in the Bengali theatre whilst redesigning Bengali theatre to befit the Indian urban tastes.

The history of Bengali theatre is thus the saga of changing tradition. Bengali theatre soon became a strong medium of expression to mirror the socio- political and contemporary issues to the common Indians. The main aim was then to make the mass aware of the then socio political scenario. Quite ideally therefore the playwrights, director and even the actors in Bengali theatre with their unparallel contribution illustrated the colonial fragrance in perhaps the right way. One such play of that time was Nildarpan, which depicted the misery of the indigo cultivators. Dinabandhu Mitra, with his refined creation like "Sadhabhar Ekadasi" and Lilabati, added to the maturity of the Bengali theatre whilst carrying it to the next level of maturity.

The history of Bengali theatre is thus the saga of changing tradition. Bengali theatre soon became a strong medium of expression to mirror the socio- political and contemporary issues to the common Indians. The main aim was then to make the mass aware of the then socio political scenario. Quite ideally therefore the playwrights, director and even the actors in Bengali theatre with their unparallel contribution illustrated the colonial fragrance in perhaps the right way. One such play of that time was Nildarpan, which depicted the misery of the indigo cultivators. Dinabandhu Mitra, with his refined creation like "Sadhabhar Ekadasi" and Lilabati, added to the maturity of the Bengali theatre whilst carrying it to the next level of maturity.

With the establishment of Indian People`s Theatre Association (IPTA), the history of Bengali theatre took a new turn. Theatre in Bengal then became even closer to the people. The famous stages of Bengali theatre like the Girish Mancha and star theatre then witnessed a huge change in order to befit the requirement where the aura of the "Classical dance drama " was no more and on the contrary emerged a whole new concept of theatre -- "Peoples Theatre" which was definitely "for the people and by the people".

Theatre continued to flourish in Bengal. Dwijendra Lal Roy, Girish Ghosh, Bijon Bhattacharya, Utpal Dutt, Shombhu Mitra, Balraj Sahani, Habib Tanvir and several others contributed to its maturity.

It was much later the very concept of Bengali Theatre as the representation of the age-old British colonialism gradually faded away and theatre became lot more naturalistic. However, right after independence the very demand of the realistic theatre approach was so much vibrant that Famous theatre personalities like Utpal Dutta, Shombhu Mitra and Badal Sarkar designed a whole new concept - Realistic theatre in Bengali.

That was just the beginning of a history. The trend then was to reflect the daily life, social issues, political turmoil and indeed the economic scenario of India in a realistic way. The post-Independence period offered a marked change in Bengali theatre whilst making it rather stylistic in its approach. With the coming of the theatre personalities like Badal Sircar, Mohit Chattopadhya, Arun Mukherjee and others the timeline of Bengali theatre gained that desired contour.

The trend which started is still continuing and today the contemporary Bengali theatre with its distinct aura and Natya has become one of the well-recognized art form.

Religious Influence on Bengali Theatre

Religion and spiritually, in general, influenced Bengali theatre to a large extent. Many theatre writers, led by of course, Girish Ghosh strived hard to make sure that people realized the religious and spiritual richness that Hinduism had. So, Girish Chandra Ghosh did find a way of writing for the theatre that would incorporate both native as well as foreign traditions into a final product, unique even in its own hybridity. Hybridity, processed through Ghosh`s genius, thus earned validity as an emergent form of its own. Bilwamangal Thakur, as a result, is a bhakti play in the tradition of Baishnab drama and Jatra. At the same time it is also a conflict and denouement-driven Western style play, divided into five acts. The play, however, ends with a sort of an epilogue that is situated outside the scenic/episodic structure of the text.

Religion and spiritually, in general, influenced Bengali theatre to a large extent. Many theatre writers, led by of course, Girish Ghosh strived hard to make sure that people realized the religious and spiritual richness that Hinduism had. So, Girish Chandra Ghosh did find a way of writing for the theatre that would incorporate both native as well as foreign traditions into a final product, unique even in its own hybridity. Hybridity, processed through Ghosh`s genius, thus earned validity as an emergent form of its own. Bilwamangal Thakur, as a result, is a bhakti play in the tradition of Baishnab drama and Jatra. At the same time it is also a conflict and denouement-driven Western style play, divided into five acts. The play, however, ends with a sort of an epilogue that is situated outside the scenic/episodic structure of the text.

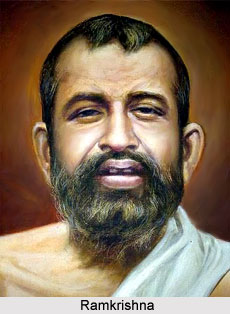

Coming of Ramakrishna in Bengali Theatre

Turning the public theatre holy was a project that Girish Ghosh, the erstwhile atheist, had undertaken under the influence of Shri Ramakrishna (1836-86), the saint-teacher, who became the spiritual guru of many leading theatre practitioners in the last decades of the nineteenth century. Ghosh`s encounter with Sanyasaa of Ramakrishna does not span a long period but the connection between the two had a big impact on the former.

Among the first babus to be attracted to the gospel of Ramakrishna and the man himself was Keshab Chandra Sen (1838-84), the leading preacher of the Brahmo Samaj started by Raja Ram Mohan Roy that propagated an abstract monotheistic interpretation of Hinduism. But ideas and Religious Teachings Of Ramakrishna were far from abstract. His conception of divinity and worship of the Almighty was deeply entrenched in idolatry and concrete performative devotional practices that, however, were non-sectarian, syncretic and integrative. Keshab Chandra Sen`s attraction to and his role in popularizing Ramakrishna among the Bengali intelligentsia signalled, among other things, the ultimate failure of the Brahmo Samaj movement to create a popular appeal among the larger Bengali Hindu community of the late nineteenth century and unite it.

Among the first babus to be attracted to the gospel of Ramakrishna and the man himself was Keshab Chandra Sen (1838-84), the leading preacher of the Brahmo Samaj started by Raja Ram Mohan Roy that propagated an abstract monotheistic interpretation of Hinduism. But ideas and Religious Teachings Of Ramakrishna were far from abstract. His conception of divinity and worship of the Almighty was deeply entrenched in idolatry and concrete performative devotional practices that, however, were non-sectarian, syncretic and integrative. Keshab Chandra Sen`s attraction to and his role in popularizing Ramakrishna among the Bengali intelligentsia signalled, among other things, the ultimate failure of the Brahmo Samaj movement to create a popular appeal among the larger Bengali Hindu community of the late nineteenth century and unite it.

Meeting of Ramkrishna and Girish Ghosh

Girish Chandra Ghosh had met Ramakrishna first time soon after, the former had recovered from a serious disease in 1880s. This "miraculous" recovery eventually became reason for him to give up atheism and find solace in divine faith. Ghosh had seen Ramakrishna twice at babu houses in Kolkata, where the holy man had been invited to preach. None of these experiences had had a major impact on him; he continued to remain indifferent to Ramakrishna, although his curiosity had been whetted. Then, in 1884, Ghosh launched his production of Chaitanyaleela on the life and times of the medieval Vaishnab Bhakti cult leader Nimai Chaitanya (1486-1534) at the Star Theatre, Kolkata and nothing more than exchanges of social niceties in the foyer of the theatre occurred between the two men on that night. But at the end of the performance, Ramakrishna did go backstage and meet the actors, particularly Binodini Dasi who had played (in cross-gendered casting) the role of Chaitanya.

Ghosh met Ramakrishna a third time at yet another babu residence where both had discussion about various philosophies of life. Thereafter, Ghosh met Ramakrishna Paramahansa at regular intervals and, once, even insulted the master in a drunken stupor when Ramakrishna refused to agree to be born again as his son! But his belief and dependence on Ramakrishna grew quickly and with remarkable intensity. So much so that Ghosh contemplated giving up the theatre and devoting himself entirely to serving his guru, to which Ramakrishna objected. Ghosh lamented no more and devoted himself to the karma of his life - theatre.

Ghosh met Ramakrishna a third time at yet another babu residence where both had discussion about various philosophies of life. Thereafter, Ghosh met Ramakrishna Paramahansa at regular intervals and, once, even insulted the master in a drunken stupor when Ramakrishna refused to agree to be born again as his son! But his belief and dependence on Ramakrishna grew quickly and with remarkable intensity. So much so that Ghosh contemplated giving up the theatre and devoting himself entirely to serving his guru, to which Ramakrishna objected. Ghosh lamented no more and devoted himself to the karma of his life - theatre.

Influence of Ramkrishna in Bengali Theatre

Ramakrishna died in 1886, but that did not destroy Ghosh. On the contrary, it strengthened him to stay on course. In fact, it was in the post-Ramakrishna phase of his career that Ghosh wrote some of his best plays and directed some of his best productions. In turn it was Bengali theatre that enhanced. Until he met Ramakrishna, Ghosh was a greatly disturbed man whose life had been beset with innumerable tragedies. He had led the reckless life of a social rebel, living in the forgetful oblivion of hedonistic pleasure seeking. But all of his atheism, hedonism and rebellion could not explain the social situation around him; he had no control over it. The appearance of Ramakrishna in his life gave him a tool that would help him make sense of the world he inhabited.

Ramakrishna`s influence on Bengali theatre has been tremendous, with far-reaching consequences. His intimate contact with theatre people and their admiration for him sanctified the theatre and helped dissipate much of the anti-theatrical prejudice of the Bengali bhadralok community. Ramakrishna, who was to be canonized posthumously as a modern day avatar of Lord Vishnu, had `rescued` the fallen theatre practitioners and turned the profane space of representation into an extension of the place of worship. With his touch, the Bengali public theatre had become a miraculous, spectacular site for imaging/imagining divinities of many sorts.

The change in the social status of the Bengali public theatre that set in during the last two decades of the nineteenth century was supported by a parallel aesthetic development. With the help of Ramakrishna, Ghosh helped establish a new creed for hybridity in the Western-style Bengali theatre. Ramakrishna`s earthy, folk wisdom informed Ghosh and his alert sensibility that was already engaged in negotiating a creative space between cultures. It augmented Girish Chandra Ghosh`s sensibility with a philosophical base that helped recreate a form of performance that had generally modelled itself on a Western paradigm - the proscenium stage, the audience in the dark behind the invisible fourth wall, concert hall-style auditorium, action-driven drama, realism and all its attendant characteristics.

Hindu Nationalism of Bengali Theatre

Hindu nationalism of Bengali theatre, with time, became a crucial part of theatre culture in India. Bengali Plays started to be written in such a manner that it`s helped in creating general awareness among people. The public theatre had transformed into a desire to arouse nationalist sentiments and inspire patriotism among its audience. This needs to be seen within the larger social framework of Hindu revivalism that marked the 1870s in Bengal. The spirit of revivalism, coming in succession to the reformist movements of the earlier period, was inspiring the literati to not only invent but also narrate the idea of India as a nation.

The intelligentsia of Kolkata was no longer willing to be content with social farces and comedies. Social conditions now needed to be seen through the lenses of nationhood and as connected to a sense of history, defined and informed by a Hindu consciousness. The Brahmo Samaj movement at the turn of the century, led by Ram Mohan Roy, had turned the eyes of a section of the Hindu intelligentsia of Kolkata towards a close inspection of Hindu philosophy. The Brahmo movement that had proposed a recasting of Hinduism, especially its polytheistic practices, into European notions of liberalism, had led to a crisis in Hindu consciousness of the late nineteenth century. At this level the neo-Hindu movement went beyond the confines of an intellectual reassessment to turn into a quest for self-discovery. This revivalism demanded the fostering of a new kind of idealized social bonding that would give fresh life to a society that, the intelligentsia believed, had manifestly degenerated into spiritual bankruptcy in due course of historical process.

Within the next few years, this need for a new sociality, the notion of a newly invested jati (race), collapsed into a set of more readily and popularly understandable notions of swadesh (one`s own nation) and swa-jati (one`s own race). There was a new populist context to it - the nation needed to be peopled, i.e. the idea of the nation needed the bedrock of popular consensus; popular support was a necessary ingredient for nationalism to succeed. Thus, it became absolutely necessary for the literati to indoctrinate and "educate" the lower classes with its opinions to feed and enlarge the "national", and the theatre was an incredibly lucrative medium for that purpose.

In 1874, a new kind of play appeared in Bengali public theatre: the short patriotic "masque" accompanying the featured full-length play of the evening. Short skits - between, before or after the main attraction of the evening were not new to the stages of Bengali theatre; early in the Bengali public theatre, satirical pantomimes (pancharanga) and the one-person playlet (mastered by Ardhendu Shekhar Mustaphi) had been introduced as appetizers to the feature productions of the evening in response to the same tradition in the English theatres of Kolkata. But the satirical intent of the pancharanga had been replaced with a more serious scheme; this new version had something novel for its subject matter: devotion to the nation. On 28 March 1874, the Great National Theatre presented along with the full-length comedy Jamai Barik (The Son-in-Law`s Lay) by Dinabandhu Mitra, a 15-minute masque by Kiranchandra Bandyopadhyay titled Bharat Mata (Mother India).

Obviously, Kiranchandra Bandyopadhyay`s playlet led to a proliferation of more masques of this type, for patriotism and profit. A significant variation to the theme, however, was contributed by Harachandra Ghosh in his Bharati Dukhini (Sad Mother India), this time a slightly longer play but still within the same genre, where Mother India converses with her daughters from various parts of the British Indian Empire - Bengal, north India, Rajasthan, south India, the Deccan, etc. Girish Ghosh`s dramaturgy is based on the notions, often stereotypical, the Bengali literati held of the other races in British India. These regional daughters, appearing like in a pageant, converse with their Mother about both the virtues and foibles of their respective regions and the peoples they represent.

Political Dramas in Colonial Bengali Theatre

Political dramas in colonial Bengali theatre have been written, acted and appreciated by many. Plays like Nildarpan, or written Dinabandhu Mitra or other plays stirred a lot of heat among audiences. More plays of so-called social protest, a large number of them in the darpan style, followed suit; plays that purported to hold up a mirror, as it were, to the oppressive ills of society. Most notable among them were Prasanna Mukhopadhyay`s Palligram Darpan [Mirror of Rural Life (1873)] on the troubled life of villagers, Mir Masharraf Hossein`s Jamidar Darpan [The Landowner`s Mirror (1873)], about the sufferings of the peasant class in the hands of the land-owning babus and two plays by Dakshinaranjan Chattopadhyay-Cha-kar Darpan [The Tea-Planter`s Mirror (1875)], dealing with the poor working conditions in the British owned tea-estates in North Bengal and Jail Darpan [Mirror of the Prison (1876)] that showed the terrible life of prisoners in the jailhouses of Bengal. There were plays; dramas there were being written to make a political statement. Plays during that time were often used to make a political statement.

All four plays drew the fire of the British and even of some prominent members of the Bengali intellectual elite who had by this time, generally, done a volte-face from siding with the peasants and/or opposing the European planters to defending their own economic interests as (often absentee) landlords.

Almost all of these plays, one has to note, were written in the safety of the cities, by writers who did not belong to the classes that were the immediate subject of the plays; they were urban intellectuals who mostly fed off the land they possessed in the countryside

The objectives of the plays, therefore, are not always at par with their contents. As a result, they read more like patronizing gestures the urban gentry were making to their own socio-political contradictions, defining their role in Bengali society as ideological leaders and enforcers of the discipline of the dominant. The plays, in this context become theatrically projected protests against the atrocities the colonial rulers performed on the lower classes, to whose exploitation, ironically, the urban gentry also contributed quite directly.