About Urdu Literature

Urdu literature has, since its inception, attracted attention due to its long and vibrant history, that is perpetually tied to the evolution of that very language, Urdu, in which it is penned. While the language tends to be profoundly overshadowed by poetry, the array of expression attained in the copious annals of a few significant verse forms, especially the ghazal and nazm (an Urdu poetic form that is usually scripted in rhymed verse), has led to its continual development and growth into other styles of writing, including that of the short story, or afsana. Urdu literature today commands foremost popularity in the eastern countries of India and Pakistan, also generating interest in far-off lands overseas.

Urdu literature has, since its inception, attracted attention due to its long and vibrant history, that is perpetually tied to the evolution of that very language, Urdu, in which it is penned. While the language tends to be profoundly overshadowed by poetry, the array of expression attained in the copious annals of a few significant verse forms, especially the ghazal and nazm (an Urdu poetic form that is usually scripted in rhymed verse), has led to its continual development and growth into other styles of writing, including that of the short story, or afsana. Urdu literature today commands foremost popularity in the eastern countries of India and Pakistan, also generating interest in far-off lands overseas.

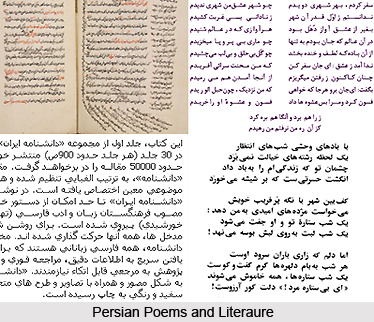

Urdu literature may be said to unearth its time of origin some time around the 14th century in India, within the arena of classy and refined aristocracy of Persian courts. The presence of Muslim aristocracy in a predominating Hindu India, which being clearly manifested, did not so sweepingly dictate the consciousness of the Urdu poet as much as did the persisting traditions of Islam and Persia. The very colour of the Urdu language, with a lexicon virtually uniformly divided between Sanskrit-derived Prakrit and Arabo-Persian words, was a reflection of the inventiveness of cultural incorporation. Yet, there could still be witnessed the doggedness on retaining what was crème de la crème and most beautiful about the lands of Afghanistan and Persia; which significantly had overridden the phenomena of evolvement of Urdu literature.

If looked into closely and in a well-researched manner, Urdu literature indeed had begun its first step from the overshadow of the Persian invasions and their consequent permanent stay-back in India. The Persians had, incidentally, comes into India at such a time, when India was out-and-out dominated by Hinduism, Hindu customs, rituals and Hindutva from every nook and corner. As such, ancient Indian literature was basically restricted and exclusive for the high-classed and religiously zealous men of the Brahmin caste and creed. Sanskrit, Pali and Prakrit had dominated the erudite class of Brahmins, which was horrifically shaken to its bone when the Islamic encroached upon India with their fashion of ruling and of course, literature. The Muslim rulers virtually had made Sanskrit walk onto the path of extinction, with the eclipsing replacement of ancient Hindu languages with Urdu literature and language.

After the advent of the series of Muslim rulers and their dynasty of royalties, Urdu literature was gradually given a distinct version with dollops of Persian influence, which gradually was darkened by the Indianised version of the Urdu dialect, all courtesy being accredited to the Mughal Empire. However, evolvement of Urdu literature in India can be divided into three fundamental categories, comprising: Ancient Period in Urdu Literature, Medieval Period in Urdu Literature and, Modern Period in Urdu Literature.

Ancient Period in Urdu Literature

Ancient period in Urdu literature was wholly the time of redefining and making Urdu language popular and well acceptable to both the Indian mass and class. Urdu literature by the time of advent in India, was already a declared rage and esteemed as a classy version in the erstwhile Persia and its development of literature. As such, with the ushering in of the Islamic rule and their kings in India, the dwellers of a predominantly Hindu India were welcomed with an almost culture shock, with complete overhaul of everything previous. Literary traditions, writing style, producing of work pieces by the ancient Hindu literature were shadowed by ancient Urdu literature, still then gladly inclined towards believing Persian Urdu as authentic, as opposed to Indian maturation of the Urdu dialect. However, the rest of development of history was yet to come.

Ancient period in Urdu literature was wholly the time of redefining and making Urdu language popular and well acceptable to both the Indian mass and class. Urdu literature by the time of advent in India, was already a declared rage and esteemed as a classy version in the erstwhile Persia and its development of literature. As such, with the ushering in of the Islamic rule and their kings in India, the dwellers of a predominantly Hindu India were welcomed with an almost culture shock, with complete overhaul of everything previous. Literary traditions, writing style, producing of work pieces by the ancient Hindu literature were shadowed by ancient Urdu literature, still then gladly inclined towards believing Persian Urdu as authentic, as opposed to Indian maturation of the Urdu dialect. However, the rest of development of history was yet to come.

Ancient period in Urdu literature in India was primarily answered by the gradual development of poetry and further prose structure, somewhere around the 15th century. The man who had exercised the most profound influence on the initial growth of not only Urdu literature, but the language itself (which meanwhile truly had taken shape as differentiated from both Persian and proto-Hindi approximately around the 14th century) was the legendary Amir Khusro. Credited, indeed, with the very structurisation and rationalisation of northern Indian classical music, acknowledged as Hindustani, Amir Khusro had penned works in both Persian and Hindavi, frequently devoting himself in nifty amalgamation of the two. While the couplets that come down from him are illustration of a latter-Prakrit Hindi devoid of Arabo-Persian vocabulary, his influence on court wazirs and writers truly perhaps had been mighty. This concept has almost been established by historians, because a century after his passing away, Quli Qutub Shah (founder of the Qutb Shahi dynasty, which ruled the Sultanate of Golconda in southern India from 1518 to 1687) was viewed to fancy for a language that can safely be branded to be Urdu.

According to yet another historical view of ancient period of Urdu literature in India, the language`s umpteen primitive forms can be traced back to Muhammad Urfi (Tadhkirah - 1228 A.D.), Amir Khusro (1259-1325 A.D.) and, Kwaja Muhammad Husaini (1318-1422 A.D.). As Urdu started to witness its prospering in the kingdoms of Golconda and Bijapur, the earliest writings in this language were gradually established in the Dakhni (Deccani) dialect of south India. The Sufi saints were the earliest advocates of the Dakhni Urdu. Sufi-saint Hazrat Khwaja Banda Nawaz Gesudaraz is deemed to be the first prose writer of Dakhni Urdu and particular treatises like Merajul Ashiqin and Tilawatul Wajud are accredited to him, but his authorship is however open to fields of uncertainty. The first literary work in ancient Urdu literature is that of Bidar poet Fakhruddin Nizami`s mathnavi `Kadam Rao Padam Rao`, penned sometime within 1421 and 1434 A.D. Kamal Khan Rustami (Khawar Nama) and Nusrati (Gulshan-e-Ishq, Ali Nama and Tarikh-e-Iskandari) were the significant other two great poets of Bijapur. Muhammed Quli Qutb Shah, the greatest of the Golconda emperors, a distinguished poet, is accredited with introducing a secular content to the otherwise largely religious Urdu poetry. Quli Qutb Shah`s poetry was centred entirely upon love, nature and social life of the day.

According to yet another historical view of ancient period of Urdu literature in India, the language`s umpteen primitive forms can be traced back to Muhammad Urfi (Tadhkirah - 1228 A.D.), Amir Khusro (1259-1325 A.D.) and, Kwaja Muhammad Husaini (1318-1422 A.D.). As Urdu started to witness its prospering in the kingdoms of Golconda and Bijapur, the earliest writings in this language were gradually established in the Dakhni (Deccani) dialect of south India. The Sufi saints were the earliest advocates of the Dakhni Urdu. Sufi-saint Hazrat Khwaja Banda Nawaz Gesudaraz is deemed to be the first prose writer of Dakhni Urdu and particular treatises like Merajul Ashiqin and Tilawatul Wajud are accredited to him, but his authorship is however open to fields of uncertainty. The first literary work in ancient Urdu literature is that of Bidar poet Fakhruddin Nizami`s mathnavi `Kadam Rao Padam Rao`, penned sometime within 1421 and 1434 A.D. Kamal Khan Rustami (Khawar Nama) and Nusrati (Gulshan-e-Ishq, Ali Nama and Tarikh-e-Iskandari) were the significant other two great poets of Bijapur. Muhammed Quli Qutb Shah, the greatest of the Golconda emperors, a distinguished poet, is accredited with introducing a secular content to the otherwise largely religious Urdu poetry. Quli Qutb Shah`s poetry was centred entirely upon love, nature and social life of the day.

According to ancient period of Urdu literature in India, the word Urdu (court or camp) is derived from the Persianised Turkish word (Ordu), which stands for "the camp of a Turkish army". North Indian Muslims with their own set of dialects had moved to South and Central India and had henceforth settled amongst the Marathas, Kannadigas and Telugus. These dialects thus had formed the basis of a literary speech, acknowledged as Dakhni or the `Southern Speech`, and were mouthed in the Deccan region. Later, north Indian Muslims, who had arrived with Aurangzeb for his conquests down south and some Dakhni writers, construed the possibility of chiseling out a new language. This language would be based on the literary traditions of Dakhni and have the Persian script along with generous usage of Perso-Arabic words, idioms and theme ideas, precisely giving rise to ancient Urdu literature, awaiting its further development.

Medieval Period in Urdu Literature

Medieval period in Urdu literature follows in close succession to its ancient counterpart, which can securely be stated as the period during which Urdu had gained its strong foothold in a predominant Hindu cultural India. However, after the language`s decisive and path-breaking initiation trial run, the time had come for Urdu to witness its further approval by the Indian cultural mass and class, who had started to take massive interest in the Arabic language. Medieval period of Urdu hence was flagged off by its tremendous spread to South India, by way of North India. The Sufi sages, with the help of Deccani rulers, were the prime motivators for the people of South to begin their fresh style of dialect and lexicon to call their own. As such, a new version of medieval Urdu literary period could be witnessed in the form of the Dakhini dialect, implying the `Southern speech`, spoken by people of north India migrating to the south.

Medieval period in Urdu literature follows in close succession to its ancient counterpart, which can securely be stated as the period during which Urdu had gained its strong foothold in a predominant Hindu cultural India. However, after the language`s decisive and path-breaking initiation trial run, the time had come for Urdu to witness its further approval by the Indian cultural mass and class, who had started to take massive interest in the Arabic language. Medieval period of Urdu hence was flagged off by its tremendous spread to South India, by way of North India. The Sufi sages, with the help of Deccani rulers, were the prime motivators for the people of South to begin their fresh style of dialect and lexicon to call their own. As such, a new version of medieval Urdu literary period could be witnessed in the form of the Dakhini dialect, implying the `Southern speech`, spoken by people of north India migrating to the south.

The other important writers of medieval period in Urdu literature in the Dakhni dialiect comprised Shah Miranji Shamsul Ushaq (Khush Nama and Khush Naghz), Shah Burhanuddin Janam, Mullah Wajhi (Qutb Mushtari and Sabras), Ghawasi (Saiful Mulook-O-Badi-Ul-Jamal and Tuti Nama), Ibn-e-Nishati (Phul Ban) and Tabai (Bhahram-O-Guldandam). Mullah Wajhi`s Sabras is deemed as a masterpiece of great literary and philosophical value. Vali Mohammed or Vali Dakhni (Diwan) was one of the most creative and inexhaustible Dakhni poets of the medieval period of Urdu in India. He was the man behind the scrupulous development of the form of the modern ghazal one is aware of now. When Vali Mohammad`s Diwan (Collection of Ghazals and other poetic genres) had reached Delhi, the poets of that Islam-dominated city who were engrossed in composing poetry in Persian language, were much impressed and also embarked on authoring poetry in Urdu, which they titled as Rekhta.

Urdu literature during its medieval period, in this context, however generally compiled more of poetry as opposed to prose. The prose element of medieval Urdu literature was predominantly restricted to the ancient form of long-epic stories, referred to as Daastaan. These long-epic stories would primarily address magical and otherwise fantastical creatures and events in an extremely perplexed plot.

Shamsuddin Waliullah, a celebrated poet of the Dakhni dialect of Urdu literature during the medieval period, in fact had initiated the North Indian Urdu dialect in a vastly circulated manner. Other poets also joined in this new literary rush and began to come to Delhi afterwards. `Delhi Urdu` as a Muslim language thus was born in a ringing process. Court circuits, Persian and Arabic scholars and principally the Muslims of Delhi conformed to this language with much avidity, and from the end of the 18th century, the Mughal house virtually had inclined permanently towards Urdu. For the first 60 years or so authority and sway of the Dakhni poets, Sufi thinking and an Indian ness of diction had predominated over Urdu literature.

Shamsuddin Waliullah, a celebrated poet of the Dakhni dialect of Urdu literature during the medieval period, in fact had initiated the North Indian Urdu dialect in a vastly circulated manner. Other poets also joined in this new literary rush and began to come to Delhi afterwards. `Delhi Urdu` as a Muslim language thus was born in a ringing process. Court circuits, Persian and Arabic scholars and principally the Muslims of Delhi conformed to this language with much avidity, and from the end of the 18th century, the Mughal house virtually had inclined permanently towards Urdu. For the first 60 years or so authority and sway of the Dakhni poets, Sufi thinking and an Indian ness of diction had predominated over Urdu literature.

The medieval Urdu poetry indeed had matured under the dominating presence of Persian poetry. Unlike Hindi poetry, which had developed solely out from the Indian soil, Urdu poetry was initially nurtured and bred with Persian words and metaphors. Sirajuddin Ali Khan Arzu and Shaikh Sadullah Gulshan were the earliest boosters of Urdu language in North India. Sauda has been described as the principal and leading satirist of Urdu literature in the medieval period, spanning throughout the 18th century. His Shahr Ashob and Qasida Tazheek-e-Rozgar are considered as chefs-d`oeuvre of Urdu literature. Mir Hassan`s mathnavi Sihr-ul-Bayan and Mir Taqi Mir`s mathnavies had filled up much of the remaining absence of Urdu language in North India, furnishing a distinct Indian touch to the language.

The phrase `Four Pillars of Urdu` has pertinently been accredited to the four early poets of Urdu literature, precisely in the medieval period, including: Mirza Jan-i-Janan Mazhar (1699-1781) of Delhi, Mir Taqi (1720-1808) of Agra, Muhammad Rafi Sauda (1713-1780) and Mir Dard (1719-1785). During this period, Lucknow had become a contending centre for the patronage of Urdu literature, and masters of Urdu poetry received moral boost from the court of the Nawab. The last Mughal emperor, Bahadur Shah Zafar was a poet equipped with an exclusive style, characterised by complex rhymes, excessive word play and use of idiomatic language. The emperor indeed has composed four voluminous Diwans. Before the national uprising of 1857 (more respected as Sepoy Mutiny, the First War of Indian Independence), the reign of Bahadur Shah Zafar had witnessed the lush springing of Urdu poetry, immediately succeeded by the chilly winds of autumn. Shaik Ibrahim Zauq had served as the Bahadur Shah`s mentor in poetry. Next only to Muhammad Rafi Sauda, Shaik Ibrahim Zauq is considered the most spectacular composer of qasidas (panegyrics). Hakim Momin Khan Momin was in the habit to pen ghazals in a style distinctive to him. He had employed ghazal exclusively for expressing emotions of passion and affection.

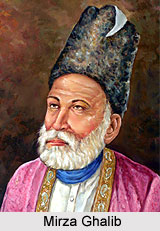

Significantly enough, any account of Urdu literature during medieval period in India, forever remain incomplete without the mention of Mirza Asadullah Khan Ghalib (tremendously admired as Mirza Ghalib) (1797-1869), who is deemed the greatest of all the Urdu poets yet to have arrived to this universe. With his obsession and ardour for originality, Ghalib had ushered in a `renaissance` in Urdu poetry. A Sufi mystic, Mirza Ghalib penned both in Urdu and Persian and through his letters, ushered in an era of literary history and criticism. His humane feelings, Sufi sentiments, simplicity of lines and depth of observations made Ghalib the greatest Urdu and Persian poet.

Modern Period in Urdu Literature

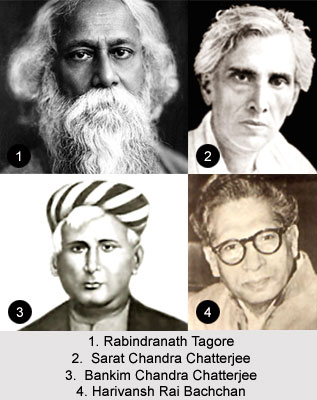

The modern period in rdu literature, can be counted from the termination of the Mughal Empire with Bahadur Shah Zafar and his Urdu-penning genius, and the beginning of the prolonged colonial rule in India. The First War of Indian Independence, legendary as the Sepoy Mutiny, was crucial in the regard of producing several Urdu litterateurs, both in the arena of prose and poetry. Modern Urdu literature during the pre-independence period, also had given birth to several revolutionary thinkers, comprising fiery commentaries, Hindu writers in the Persian language and, birth of the short story. During the post-Mizra Ghalib period, Dagh (b. 1831) had emerged as a prominent poet, whose poetry was noted by its purity of idiom and minimalism of language and thought.

The modern period in rdu literature, can be counted from the termination of the Mughal Empire with Bahadur Shah Zafar and his Urdu-penning genius, and the beginning of the prolonged colonial rule in India. The First War of Indian Independence, legendary as the Sepoy Mutiny, was crucial in the regard of producing several Urdu litterateurs, both in the arena of prose and poetry. Modern Urdu literature during the pre-independence period, also had given birth to several revolutionary thinkers, comprising fiery commentaries, Hindu writers in the Persian language and, birth of the short story. During the post-Mizra Ghalib period, Dagh (b. 1831) had emerged as a prominent poet, whose poetry was noted by its purity of idiom and minimalism of language and thought.

By the beginning of the 18th century, the modern period in Urdu literature, a more stylish and classy North Indian variation of the language began to move forward through the authorships of Shaikh Zahooruddin Hatim (1699-1781 AD), Mirza Mazhar Jan-e-Janan (1699-1781 AD) Khwaja Mir Dard (1719- 1785 AD), Mir Taqi Mir (1722-1810 AD), Mir Hasan (1727-1786 AD) and Mohammed Rafi Sauda (1713-1780 AD). Mir`s works, apart from his six Diwans, comprise Nikat-ush-Shora (Tazkira) and Zikr-se-Mir (Autobiography). Shaik Ghulam Hamdani Mushafi (1750-1824), Insha Allah Khan (Darya-e-Latafat and Rani Ketaki), Khwaja Haider Ali Atish, Daya Shankar Naseem (mathnavi: Gulzare-e-Naseem), Nawab Mirza Shauq (Bahr-e-Ishq, Zahr-e-Ishq and Lazzat-e-Ishq) and Shaik Imam Bakhsh Nasikh were the early poets in Urdu literature of Lucknow. Mir Babar Ali Anees (1802-1874) also had contributed to the fast escalating modern Urdu literature in India, excelling in the art of writing marsiyas.

The most illustrious poets in Urdu literature of the pre-modern period in India, were Muhammad Ibrahim Zauq (1789-1854) of Delhi and Nazmuddaulah Dabiru-i-Mulk. Modern period in Urdu literature spans the time from the last quarter of the 19th century, till the present day and can broadly be divided into two periods: the period of the Aligarh Movement started by Sir Sayyid Ahmad and the period influenced by Sir Muhammad Iqbal, followed by the Progressive movement and movements of Halqa-e-Arbab-e-Zouq, Modernism and Post modernism.

The most illustrious poets in Urdu literature of the pre-modern period in India, were Muhammad Ibrahim Zauq (1789-1854) of Delhi and Nazmuddaulah Dabiru-i-Mulk. Modern period in Urdu literature spans the time from the last quarter of the 19th century, till the present day and can broadly be divided into two periods: the period of the Aligarh Movement started by Sir Sayyid Ahmad and the period influenced by Sir Muhammad Iqbal, followed by the Progressive movement and movements of Halqa-e-Arbab-e-Zouq, Modernism and Post modernism.

However, Altaf Husain Panipati (1837-1914), known as Hali or `the Modern One`, is the authentic trailblazer of the modern spirit in Urdu poetry. In the meantime, Hindu writers of the Urdu language also were not left far behind and among the earliest writers were Pandit Ratan Nath Sarshar (author of Fisana-e-Azad) and Brij Narain Chakbast (1882-1926). Prominent among the lot of Hindu Urdu writers are: Firaq Gorakhpuri, Pandit Ratan Nath Sarshar (Fasana-e-Azad) and Brij Narain Chakbast (1882 - 1926), who composed Subh-e-Watan and Tilok Chand Mahrum (1887-1966), who composed Andhi and Utra Hua Darya, Krishn Chander, Rajindar Singh Bedi, Kanhaiyalal Kapur, Upendar Nath Ashk, Jagan Nath Azad, Jogender Pal, Balraj Komal and Kumar Pashi. One of the most famous poets of modern Urdu is Sayyid Akbar Husain Razvi Allahabadi (1846-1921), who had possessed a flair for impromptu composition of satiric and comic verses. After 1936, Urdu literature picked up a progressive attitude and leaned more towards the problems of life.

Poetry, novels, short stories and essays were the basic avenues of liberal expression in Urdu literature of the modern period. The main exponents of this new line of approach were the short story writers, comprising Muhammad Husain Askari, Miranji, Faiz Ahmad `Faiz`, Sardar Ali Jafari and Khwajah Ahmad Abbas. Munshi Premchand, the greatest novelist of Hindi literature, had, for a time period, begun writing in Urdu and later switched to Hindi. Shibli Nomani (b.1857) is esteemed as the father of modern history in Urdu literature. He virtually had yielded several works based on historical research, especially on Islamic history, like Seerat-un-Noman (1892) and Al Faruq (1899). Shibli Nomani also had produced substantial works like Swanih Umari Moulana Rum, Ilmul Kalam (1903), Muvazina-e-Anis-o-Dabir (1907) and Sher-ul-Ajam (1899).

Short story in Urdu literature of the modern period began with Munshi Premchand`s Soz-e-Vatan (1908). His short stories comprehend almost a dozen volumes, comprising Prem Pachisi, Prem Battisi, Prem Chalisi, Zad-e-Rah, Vardaat, Akhri Tuhfa and Khak-e-Parvana. Mohammed Hussan Askari and Khwaja Ahmed Abbas are counted among the leading luminaries of the Urdu Short story. The Progressive Movement in Urdu fiction had picked up momentum under Sajjad Zaheer (1905-1976), Ahmed Ali (1912-1994), Mahmood-uz-Zafar (1908-1994) and Rasheed Jahan (1905-1952). Urdu literature authors like Rajender Singh Bedi and Krishn Chander (1914-1977) had exhibited out-and-out dedication to the Marxist philosophy in their writings. Krishn Chander`s Adhe Ghante Ka Khuda is one of the most unforgettable stories in Urdu literature of modern era. His other renowned short stories comprise Zindagi Ke Mor Par, Kalu Bhangi and Mahalaxmi Ka Pul. Rajender Singh Bedi`s Garm Kot and Lajvanti are enlisted amongst the chefs-d`oeuvre of Urdu short story. Manto, Ismat Chughtai and Mumtaz Mufti form an unlike sort of Urdu writers, who focused upon the "psychological story" as opposed to the "sociological story" of Bedi and Krishn Chander. Ahmad Nadeem Qasmi (b.1915) is one more foremost name in Urdu short story. His important short stories include Alhamd-o-Lillah, Savab, Nasib and others.

During the post-1936 period of modern Urdu literature, writers belonging to the Halqa-e-Arbab-e-Zauq dished out several good stories in the respective genre. Upender Nath Ashk (Dachi), Ghulam Abbas (Anandi), Intezar Hussain, Anwar Sajjad, Balraj Mainra, Surender Parkash and Qurratul-ain Haider (Sitaroun Se Aage, Mere Sanam Khane) are the other leaders of Urdu short story. Several stellar fiction writers emerged from the city of Hyderabad in the present times, comprising Jeelani Bano, Iqbal Mateen, Awaz Sayeed, Kadeer Zaman, Mazhr-uz-Zaman and others.

Novel writing in Urdu literature of the modern period can be traced to Nazir Ahmed, (1836 - 1912) who had penned several novels like Mirat-ul-Urus (1869), Banat-un-Nash (1873), Taubat-un-Nasuh (1877), Fasana-e-Mubtala (1885), Ibn-ul-Waqt (1888), Ayama (1891) and others. Pandit Ratan Nath Sarshar (1845 - 1903)`s Fasana-e-Azad, Abdul Halim Sharar (1860 - 1920)`s Badr-un-Nisa Ki Musibat and Agha Sadiq ki Shadi, Mirza Muhammed Hadi Ruswa`s Umrao Jan Ada (1899) are some of the stalwart instances of novels and novellas scripted during the period. However, it was Munshi Premchand (1880-1936) who had endeavoured to introduce the trend of realism in Urdu novel of contemporary era. Premchand was a prolific writer who virtually had left his mark in Urdu literature too, producing numerous books. His important novels include Bazare-e-Husn (1917), Gosha-e-Afiat, Chaugan-e-Hasti, Maidan-e-Amal and Godan. Premchand`s realism received additional boost by the writers of Indian Progressive Writers` Association, like Sajjad Zaheer, Krishn Chander and Ismat Chughtai. Krishn Chander`s Jab Khet Jage (1952), Ek Gadhe Ki Sarguzasht (1957) and Shikast are ranked amongst the stupendous novels in Urdu literature. Ismat Chughtai`s novel Terhi Lakir (1947) and Qurratul-ain Haider`s novel Aag Ka Darya are measured as cardinal works in the history of Urdu novel.

In spite of Urdu literature being considered a little tilted towards Islamic lines, there still existed some great Hindu writers who embraced Urdu like their very own, like Krishan Chandar, Rajindar Singh Bedi and Kanhaiyalal Kapur. Unfortunately, the lyrical language of Urdu of the modern period no longer savors the same position that it used to in the Mughal courts of its golden blooming period. However, Urdu literature is still encouraged in states like Jammu and Kashmir, Punjab and Hyderabad. Present day Standard Hindi borrows a lot from Urdu - in domains of grammar, diction and idiom.

Influence of Indo-Anglican Culture in Urdu Literature

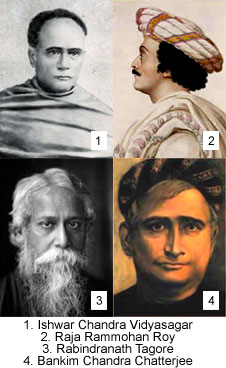

Much as Indo-Persian (Mughal) cultural conflation is represented, the manifestation of Indo-Anglican cultural conflation can be heard in the voice of poets, scholars and critics. All have, in the late-nineteenth century, amply documented the phenomenon of the reformist Indo-Anglican - Aligarh Movement, and also its influence on the careers of Maulana Azad, Altaf Husain Hali, and other writers in Urdu language.

In the year 1835, Lord William Bentinck passed legislation to propagate English education in India. During this time there was a keen desire on the part of Indians to acquire the knowledge which was considered to be the secret of the progress and efficiency of Western nations. Certainly this desire was shared by Sayed Ahmad Khan, the leader of the Aligarh Movement. Indian Muslims, it is widely agreed, were demoralised by the crushing defeat of the Mughal Empire`s last stand in 1857. Many saw its failure as the inevitable outcome of a moral and spiritual turpitude into which Indian Islam had fallen. The key to survival in a country where they were neither the indigenous people, nor any longer the ruling elite, was, in Sayed Ahmad`s eyes, to emulate the new rulers as closely as possible. He was firmly convinced that the salvation of his community lay in the assimilation of Western culture and that the best chance for securing a favourable place for Indian Muslims in British India was to forge as close a relationship as possible with the British Empire.

Aligarh writers and most respected and esteemed of them all took to heart the notion that Western cultural models were to be emulated, and that Urdu poetry had grown contemptible. English, as a language, because of their political supremacy in India, had become the new arbiters of cultural legitimacy for Indian Muslims.

Surprisingly, Altaf Husain Hali, a renowned Urdu poet, denied that his own poetry was influenced by English poetic principles, or that there was anything in his poetry that could be ascribed to a pursuit of English ways or could be castigated as an abandoning of traditional ways. This apparent contradiction offers a striking indication of the constraints under which Hali was working, and the understandable ambivalence he must have felt as to where, exactly, his loyalties lay. His piety and devotion to Islam were sincere and fundamental, which impelled him in the direction of whatever action he was able to take toward the betterment of his fellow Indian Muslims` condition. Although the Aligarh reformers openly admired British culture they drew a definite distinction between the virtues of Western civilisation and the objectionable treatment of Indians at British hands.

Influence of Indo-Persian Culture in Urdu Literature

Mughal culture as a variant of the international Islamic culture, which mainly focused on Persian language and Safavid culture as central elements in the Mughal nobility`s own identification. Indeed, command of Persian plays a large part in assessments of Urdu literature specially the poems. Even as recently as 1973 the critic Ahmed Ali praised Atish`s poetic diction in spite of an occasional vulgarized use of Persian idiom, and it was also noted earlier that Mohammad Azad indulgently overlooked Atish`s imperfect understanding of Persian in favour of his colloquial diction. Even though Nasikh was known for his erudition in Persian and Arabic language, Azad had cast aspersions on his knowledge of the two languages by writing that, of course since "Shaikh Sahib" had attended the Firangi Mahal he must have benefited somewhat from proximity to his revered and learned teachers.

Mughal culture as a variant of the international Islamic culture, which mainly focused on Persian language and Safavid culture as central elements in the Mughal nobility`s own identification. Indeed, command of Persian plays a large part in assessments of Urdu literature specially the poems. Even as recently as 1973 the critic Ahmed Ali praised Atish`s poetic diction in spite of an occasional vulgarized use of Persian idiom, and it was also noted earlier that Mohammad Azad indulgently overlooked Atish`s imperfect understanding of Persian in favour of his colloquial diction. Even though Nasikh was known for his erudition in Persian and Arabic language, Azad had cast aspersions on his knowledge of the two languages by writing that, of course since "Shaikh Sahib" had attended the Firangi Mahal he must have benefited somewhat from proximity to his revered and learned teachers.

The significance of Urdu literature`s connection to other literary traditions must not be underestimated. The aesthetics of ghazals are direct descendants from those of Persian poetry; and modern Urdu criticism was founded upon a combination of the inheritance from Persian and principles borrowed from English literature. These connections greatly influenced various writers and critics, inducing a two-fold cultural conflation.

Conflict of Indo-Persian Culture in Urdu Literature

While Urdu literature is considered as an essentially Indian cultural product, it does reflect the profound impact of Persian culture on Indo-Muslim society. It eventually came to pass, in the context of cultural authority, that Persian served as a convenient evocative term for Urdu critics and social historians, and the term "Mughal" another. These two streams of authority can be seen in the struggles to which the Delhi-Lucknow rivalry gave rise. By the 1800s, Muslim culture in India had experienced about a century`s development in the sole hands of a group of artists bred on Indian soil. The waves of Persian migration which had rolled into Mughal Empire India since the fifteenth century had now begun to subside. Most of the cultural and ruling elite, though descended from Iranians, Afghans and Turks, were purely Indian in experience.

That they do not appear to have acknowledged differences between how Iranians and Indian Muslims viewed Persian culture in India suggests that Urdu critics of the nineteenth century were indeed the products of a cultural conflation. If fact, it suggests that they may not have been aware of differences between Persian culture in Iran and Persian culture elsewhere. Certainly, an integrated view of these distinctions could not have been as accessible to Urdu critics of the last century as it is to us in the late twentieth century.

Lucknow`s ruling family represents a case of Persian descendants who were completely Indian in experience. When they broke away from the nominal control of the Mughal Empire in 1818 to take on the title of "Kings" in Avadh, they may have been anxious to establish some alternative source of legitimacy. Until then their continued claim of allegiance to the Mughal throne had carried with it a vicarious cultural legitimacy. Now, in the new absence of the legitimacy and authority which had come hand in hand with position at the Mughal court, they began to draw upon Persian connections.

Urdu was the paramount language in Lucknow, especially the literary language of the new markar, while the official court language in Mughal Delhi had remained Persian throughout the 1700s. Although it became all the rage to compose poetry in the vernacular during this time, there were few poets of Delhi who wrote exclusively in Urdu: they still saw their main avocation as Persian composition.

By 1800 the Lakhnavi populace was a quarter-century old, and the need for "refinement" of Urdu as a literary language began to be expressed by poets like Insha and, later, Nasikh. In striving toward that "refinement," the masters worked to apply the principles of Persian, since Persian provided their literary models. Here again the Indo-Persian cultural blend was acted out: the role of Persian culture in Indo-Muslim society may have become more esoteric, but Persian language itself had never lost its cultural authority.

Prose in Urdu Literature

Prose in Urdu literature, though not so popular as Urdu poetry, forms a major part among the people who are enthusiastic about the Urdu language. The component of the prose of Urdu literature was generally restricted to the olden form of long epic stories known as Dastaan which was often written in Persian language, in original form. These long and epic stories dealt with excellently magical and otherwise brilliant creatures and events in a very convoluted and complicated narrative.

As a genre, Dastaan originated in Iran, and thereafter was disseminated by folk storytellers. It was assimilated by individual authors. The plots of Dastaan are based on both folklore and classical literary subjects. Dastaan was typically popular in Urdu literature, which is typologically close to other narrative genres in Eastern literatures, such as Persian Masnawi, Punjabi Qissa, Sindhi Waqayati bait, etc., and also reminiscent of the European novel.

The oldest recognized Urdu Dastaan is Dastan-i-Amir Hamra, recorded in the early seventeenth century, and the extinct Bustan-iKhayal ("The Garden of Imagination" or "The Garden of Khayal") by Mir Taqi Khayal. Most of the narratives Dastaans were recorded in the early 19th century, thus representing contaminations of `wandering`, motifs borrowed from the folklore of the Middle East, central Asia and northern India. These also include Bagh-o Bahar (The Garden and spring) by Mir Amman, Mazhab-i-Ishq (The Religion of Love) by Nihalchand Lahori, Araish-i-Mahfil (The Adornment of the Assembly) by Hyderbakhsh Hyderi, Gulzar-i-Chin (The Flower Bed of Chin) by Khalil Ali Khan Ashq, and the smaller dastaans.

Examples of famous Dastaans in Urdu Language include:

* Nau tarz-i murassa` - Husain `Ata Khun Tahsin

* Nauaini hindi (Qissa-i Malik Mahmud Giti-Afroz) - Mihr Chand Khatri

* Jazb-i ishq - Shuh Husain Haqiqat

* Nau tarz-i murassa` - Muhammad Hadi a.k.a. Mirza Mughal Ghafil

* Araish-i mahfil (Qissa-i Hatim Tai) - Haidar Bakhsh Haidari

* Bagh o bahar (Qissa-i chahar darwesh) - Mir Amman

* Dastan-i Amir Hamza - Khalal `Ali Khan Ashk

* Talism Hoshruba - Muhammad Husain Jah

Renaissance in Urdu Literature

Renaissance stimulated cultural resurgence in the Urdu literary tradition. The Urdu writers, with a romantic fervor (a feature of Renaissance in Europe), reoriented their literature. Mohammed Hussain Azad, Altaf Hussain Ali & Shibli Numani were the precursors of the Renaissance tradition of Urdu Literature. Azad left a brilliant legacy of natural poetry and Hali initiated an innovative modification in Urdu Literature.

Quite a few numbers of works were the extraction & ornamentation of the chronicle personalities. "Al Farooq" deals with the life & achievements of formidable Farooq -i- Azam, the second Caliph of Islam. "Al- Mamoon" is the story of the achievements of Mamoon, the great, whose reign is known as the Golden Age of the Islam. "Al- Ghazali" deals with the teachings of Imam Ghazali, the greatest religious teacher.

Quite a few numbers of works were the extraction & ornamentation of the chronicle personalities. "Al Farooq" deals with the life & achievements of formidable Farooq -i- Azam, the second Caliph of Islam. "Al- Mamoon" is the story of the achievements of Mamoon, the great, whose reign is known as the Golden Age of the Islam. "Al- Ghazali" deals with the teachings of Imam Ghazali, the greatest religious teacher.

The contemporary Urdu literature, mainly concerned about the gallant stories of the great heroes, thereby stirring up the society to come out of the gloomy manacles. Shibli was the most famous critique of his time. His works, reminiscent of graphic prose & immense eloquence are the confluence of different philosophies & beliefs. The wave of Renaissance inflamed people & they came in contact with the literary trends of the world. Shibli`s critiques were the archetype of the foreign influence. "Shai-ar-ul- Azam", a renowned literary critic by Shibli dealt with the brilliant criticism of Persian poetry. "Philosophy of Islam" & "Al-Kalam" were the major treatise about Islamic Philosophy. However the Urdu Literary growth during Renaissance intended the social reforms through religious enlightenment.

Short Story in 19th Century Urdu Literature

Short story in nineteenth century Urdu literature saw a major growth during the era. At the start of the nineteenth century, printing and publishing activities at the newly founded Fort William College of Kolkata resulted in an unprecedented output of prose narratives in Urdu and Hindi. Most of these books were adaptations or translations of different classical and popular Indian tales, Persian Qissas and Masnavis, etc., meant for the instruction of British officers and employees of the British East India Company.

Short story in nineteenth century Urdu literature saw a major growth during the era. At the start of the nineteenth century, printing and publishing activities at the newly founded Fort William College of Kolkata resulted in an unprecedented output of prose narratives in Urdu and Hindi. Most of these books were adaptations or translations of different classical and popular Indian tales, Persian Qissas and Masnavis, etc., meant for the instruction of British officers and employees of the British East India Company.

Alongwith these, other works of prose fiction, printed at various Urdu presses, started to appear in considerable number, especially from the 1830s onwards. These were Urdu translations or adaptations of Persian Qissas and Perso-Arabic moral tales, of stories from the Arabian Nights, stories about the Prophet Muhammad and his companions, collections of witticisms (Lata`if), short anecdotes, and fables (Naqlen, Naqlat or Naqliyat) of humorous, amatory or other nature (originally based often on Sanskrit sources like the Shukasaptati). All these seem to have been very popular, and their traces can be distinguished in later works of fiction.

In all the major works of fiction of the period, the majority of Indian writers were influenced by the Puranic tradition of oral narratives and the memory of episodes from Ramayana and Mahabharata. The increasing number of publications based on traditional narratives in the course of the nineteenth century reveals their popularity and pervasiveness. The contents range from sexual encounters and other such adventures over jests and jokes, to moral tales. Similarly, even in the Urdu stories, the narrator cites tradition or older texts as sources for his material, however without names or titles. Certainly, quite a number of these anecdotes must have been part of oral transmission as well. In the case or such short narratives, the attitude that seems to have prevailed was typical of the treatment of poetry: they were seen as existing in a timeless mode.

The first collections of this type were produced under Gilchrist at Fort William College with the clear aim of providing material in simple prose for the language instruction of the East India Company`s British employees. Early examples are the Naqliyat compiled by the head Munshi (scribe; tutor) Mir Bahadur Ali Afsos (vol. 1: 1802, vol.2: 1806?); Akhlaq-i Hindi (Indian Ethics/Manners) compiled by Mir Bahadur Ali Husaini in 1802 and printed in 1803; Naqliyat-i Luqman (Aesop`s Fables); Lata`if-I Hindi by Lalluji Lai (Indian Witticisms, written 1800, printed 1810, 1820 and 1840); Tota Kahani (The Tales of a Parrot, 1801) by Sayid Haidar Bakhsh Haidari; Bagh-i Urdu (The Rose-garden of Urdu, 1802) by Mir Sher Ali Afsos; and Khirad Afroz (Illuminating the Intellect, 1803) by Hafizuddin Ahmad, to name some of the most popular texts. These are more or less free versions of Persian sources, the majority of which were based on Indian tales. From the number and the geographical range of later editions, it can be understood that they soon started to spread beyond the confines of classrooms for foreigners. As later Urdu and Hindi readers show, some came to be included in the syllabus for native speakers, which was in line with the practice of teaching Persian on the basis of moral and didactic tales from the Gulistan and other books on ethics and manner.

Apart from these collections sponsored by the British, similar volumes of tales, fables, witticisms and anecdotes started to appear via private/independent publishing houses. By far the greatest number seems to have been produced for entertainment. The spread of printing facilities after 1840 is reflected in the growing number of publications from that decade onwards. Different names have been used to denote short `traditional` narratives, of which Naql appears to be the broadest and most widely used, at least in the titles of different collections. It functions almost like an umbrella term covering all sorts of short stories based on tradition (written or oral or both), these varying in length between a couple of lines and several pages, the majority being less than a page long.