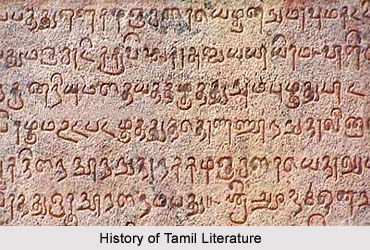

Tales for schools comprise a major part of the oral folktale in Tamil Literature. Essentially these were printed collections of oral tales printed sometime between 1800 and 1835. They were intended for the study of students of the Tamil language, mainly the civil servants of the British in the Madras Presidency. In early nineteenth-century India, because the oral tale was the most popular form of storytelling, it became the first form of printed fiction. Little is known about who read these collections of Tamil Tales. It is felt that their intended readership, in the first instance at least, was for the British civil servants in the Madras Presidency were obliged to learn a local language. The `Rules for the College of Fort St. George`, published on 1 January 1813, stated that junior civil servants must first study one of the literary south Indian languages (Tamil, Telugu, Kannada or Malayalam) and that a pass in an examination of that language earned 1000 star pagodas. Only after studying a south Indian language, could a civil servant study a second language (Marathi, Hindustani, Persian, Arabic or Sanskrit). Students in the College of Fort St. George were few; no more than two dozen throughout the 1820s and only slightly more in the 1830s and 1840s, when the College metamorphosed into the Madras University.

Tales for schools comprise a major part of the oral folktale in Tamil Literature. Essentially these were printed collections of oral tales printed sometime between 1800 and 1835. They were intended for the study of students of the Tamil language, mainly the civil servants of the British in the Madras Presidency. In early nineteenth-century India, because the oral tale was the most popular form of storytelling, it became the first form of printed fiction. Little is known about who read these collections of Tamil Tales. It is felt that their intended readership, in the first instance at least, was for the British civil servants in the Madras Presidency were obliged to learn a local language. The `Rules for the College of Fort St. George`, published on 1 January 1813, stated that junior civil servants must first study one of the literary south Indian languages (Tamil, Telugu, Kannada or Malayalam) and that a pass in an examination of that language earned 1000 star pagodas. Only after studying a south Indian language, could a civil servant study a second language (Marathi, Hindustani, Persian, Arabic or Sanskrit). Students in the College of Fort St. George were few; no more than two dozen throughout the 1820s and only slightly more in the 1830s and 1840s, when the College metamorphosed into the Madras University.

When the College of Fort St. George was first established in 1812, it immediately began to print books for these few but eager language students. The first collection of such tales, edited in 1820 by Tantavaraya Mutaliyar, head Tamil pundit at the College, was the Katamancari. The eighty-two stories in the Katamancari are mostly jocular or numskull tales from oral tradition and many are still told today. While they are brief, no more than a page, they increase in length and complexity towards the end of the book. The same Tantavaraya Mutaliyar produced a much-admired translation of the Panchatantra which again was graded so that the tales were written in progressively more difficult Tamil. He then produced a third book of tales in 1833, the Katacintamani.

The elaborate title pages of these early collections of Tamil tales, however, suggest that they faced some suspicion about their authenticity. In this early period, anyone writing or publishing a book would take pains to establish its authenticity, but books which put forward oral tales as part of a school curriculum had an even greater credibility gap to close, for they had moved not just from writing to print but also from orality to print. Originally intended for the small number of civil servants studying at the College of Fort St. George, these collections of printed oral tales soon ended up in many more hands when they entered the public school system. Already in 1826, a survey reported that nearly 200,000 students were studying in public and missionary schools where the need for textbooks was acute. In this period, prior to 1835, when official policy and private opinion still favoured the use of Indian languages, collections of folktales were the obvious choice to fulfil this educational need. Throughout the century, the printed prose version of the Panchatantra and books of miscellaneous tales (Katamancari, Katacintamani) held a central place in the primary school syllabus, along with the Tirukkural and portions of the Kamparamayanam.