Pan-Indian Music includes the entire plethora of musical influences which have gone into the making of the great body of Indian music and which in turn have been influenced by the same. Indian Music has migrated to the far-east by both land as well as sea, and history reveals the extent of musical influence that one has had on the other. The inter-mingling of musical cultures can be seen in the music of the borders of western China which had much in common with and was perhaps derivable from the music of India. For instance, the musical terms in Kuchean are said to have Sanskrit bases such as, ki-shi- kaisika, shah-shih-shadja, sha-hou ka-lan-shadja grama, etc. As for instruments, the murals in the caves of Tun-huang, an important Buddhist centre of fourth century AD, depict a number of Indian ones. Again, the Chinese bowed instrument, hu-ch`in is `foreign` to that country and the word hu is applied to "native of India and elsewhere". Japan also received the chants of Buddhist monks from India. Other Far Eastern relations of Indian Musical Instruments can be seen in the pan-pipes of Assam and the Khene of Laos. In fact the bowed instruments of Laos are very similar to the Pena of Assam and the Kenra of Orissa.

Pan-Indian Music includes the entire plethora of musical influences which have gone into the making of the great body of Indian music and which in turn have been influenced by the same. Indian Music has migrated to the far-east by both land as well as sea, and history reveals the extent of musical influence that one has had on the other. The inter-mingling of musical cultures can be seen in the music of the borders of western China which had much in common with and was perhaps derivable from the music of India. For instance, the musical terms in Kuchean are said to have Sanskrit bases such as, ki-shi- kaisika, shah-shih-shadja, sha-hou ka-lan-shadja grama, etc. As for instruments, the murals in the caves of Tun-huang, an important Buddhist centre of fourth century AD, depict a number of Indian ones. Again, the Chinese bowed instrument, hu-ch`in is `foreign` to that country and the word hu is applied to "native of India and elsewhere". Japan also received the chants of Buddhist monks from India. Other Far Eastern relations of Indian Musical Instruments can be seen in the pan-pipes of Assam and the Khene of Laos. In fact the bowed instruments of Laos are very similar to the Pena of Assam and the Kenra of Orissa.

There were also rather close cultural links between India and Indonesia. The major period of contacts was what is called the Hindu period. The domination of Indian culture commences from the early centuries of the Christian era up to about the tenth century. It was during this Indian period that a great migration of drama, dance, and music to Java and Sumatra from the parent land took place. A vast amount of evidence of this is available from the Chandi Sari reliefs (c. 750 AD) as also from early epigraphic and textual material dating from AD 821. The reliefs and sculptures of Borobodour and Angkor Vat (eighth-ninth century) as also texts like Arjunawiwaha (eleventh century) and later ones give extensive information on instruments of Indian origin. For instance, the chief drummer in an ensemble was the Padahi Manggala (Sanskrit Pataha). The Makara and Winipanchi (Vipanchi in Sanskrit) were a few chordophones of Indian sources. Of the aerophones we come across the Wangsi or Bangsi (Sanskrit Vamsi, flute), the Kahala, and so on. The Sanskrit Muraja (and the Tamil Murasu) drum becomes Murawa or Muraba; the Dundubhi was also used. Of the idiophones we have Genta (Sanskrit Ghanta), bell and Bheri a gong.

The inter-mixing of Western Asian and Indian cultural relations is so intricate that it is rather difficult to ascertain how much is influence and how much has been influenced. Scholars are of different opinions as regards this aspect. Sylvan Levi is of the opinion that

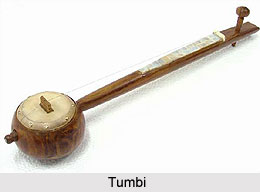

the West owes its system of notations by the initial letters of the names of the notes to Hindu music. Weber thinks that the Sanskrit term Grama, meaning a musical scale, is the root from which is derived the Arabic ah or gama ah (scale). As regards instruments, almost all words known in North India have affinities with Arabic and Persian. In the case of bowed instruments, it is seen that the Ravanahasta Veena or Ravnahatta of western India migrated to Western Asia to become the Rabonostron, the Rebec, the Rebab and finally the Violin. Another interesting migration here is that of the Kamanche or Kamanja, a bowed instrument used in Egypt and Sindh. There is seen a relation of the Kamayacha of India to Kamancha and Kamanga. The Katyayani Veena is said to have gone over as the Qanoon and the Sata Tantri Veena as the Santir to Persia and Arabia. The Santoor is still seen in Kashmir. A huge influence and inter-mingling can also be seen in the case of the Tunboor or Indian Tambura. It is difficult to ascertain its place of origin. The word is believed to be Persian; and the Arabs have the Tanbur, a long Lute. The Tanbur has also, quite possibly, affinities to the Pantur (bow small) of ancient Sumeria. Pan or Ban means a bow or even a harp. This becomes the Greek Pandora. Again, the Assyrian Pandoura was a three-stringed Lute. It is held that the original word is Indian Tambura which gets modified to Tunbura in Iran and Arabia. This would mean that the whole set of lutes in the West owe their birth to Indian sources.

The inter-mixing of Western Asian and Indian cultural relations is so intricate that it is rather difficult to ascertain how much is influence and how much has been influenced. Scholars are of different opinions as regards this aspect. Sylvan Levi is of the opinion that

the West owes its system of notations by the initial letters of the names of the notes to Hindu music. Weber thinks that the Sanskrit term Grama, meaning a musical scale, is the root from which is derived the Arabic ah or gama ah (scale). As regards instruments, almost all words known in North India have affinities with Arabic and Persian. In the case of bowed instruments, it is seen that the Ravanahasta Veena or Ravnahatta of western India migrated to Western Asia to become the Rabonostron, the Rebec, the Rebab and finally the Violin. Another interesting migration here is that of the Kamanche or Kamanja, a bowed instrument used in Egypt and Sindh. There is seen a relation of the Kamayacha of India to Kamancha and Kamanga. The Katyayani Veena is said to have gone over as the Qanoon and the Sata Tantri Veena as the Santir to Persia and Arabia. The Santoor is still seen in Kashmir. A huge influence and inter-mingling can also be seen in the case of the Tunboor or Indian Tambura. It is difficult to ascertain its place of origin. The word is believed to be Persian; and the Arabs have the Tanbur, a long Lute. The Tanbur has also, quite possibly, affinities to the Pantur (bow small) of ancient Sumeria. Pan or Ban means a bow or even a harp. This becomes the Greek Pandora. Again, the Assyrian Pandoura was a three-stringed Lute. It is held that the original word is Indian Tambura which gets modified to Tunbura in Iran and Arabia. This would mean that the whole set of lutes in the West owe their birth to Indian sources.

Cultural influences with the west have been a continuous process from centuries past. Now, even more that ever is seen a growing interest on part of the West to listen to and learn the art of Indian Music. Schools of Indian music have been established in Europe and more particularly in America where the Veena, the Mridangam, the Sarod and the Sitar are being taught among other instruments.