Notations in Indian Classical music are simply used as a skeletal framework of the actual musical performance. In India, unlike in the west, the need to co-ordinate among the different parts in a multi-part music never arose as one melody at a time is preferred in this culture. Also, notations are usually seen as a means of transmitting musical materials. But in India, written transmission is seen as being unnecessarily restrictive since improvisation lies at the very heart of the tradition of classical music as well as folk music which have been transmitted orally.

Notations in Indian Classical music are simply used as a skeletal framework of the actual musical performance. In India, unlike in the west, the need to co-ordinate among the different parts in a multi-part music never arose as one melody at a time is preferred in this culture. Also, notations are usually seen as a means of transmitting musical materials. But in India, written transmission is seen as being unnecessarily restrictive since improvisation lies at the very heart of the tradition of classical music as well as folk music which have been transmitted orally.

Yet another feature of written transmission is that the material gets shared among a number of people especially when it is published. However, the tradition of exclusivity is followed in the case of Indian classical music. Pains are taken by the teachers to transfer their knowledge only to those students who they feel are apt. In North India, many artists have taken pains to be certain that their knowledge is transmitted to only a few, if any, successors. They are extremely possessive of their traditions, which include not only specific songs but also individualistic ways of rendering a raga. Pandit Vishnu Narayan Bhatkhande of Mumbai, the musicologist who has gathered the largest collection of notated songs in North India, complained that many artists refused to sing their songs for him and allow him to notate them. Furthermore, he was refused permission to publish already notated music held in private collections. However it must be mentioned here that music has been notated more in Carnatic music tradition than in the Hindustani tradition. One reason for this is perhaps that music education has been more systematic and more widespread for a longer time in the South.

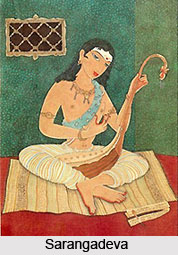

The systematic approach to learning music apparently originated in one man, Purandara Dasa (1484-1564), who was accordingly dubbed the `father of Carnatic music.

` He was one of the first to devise graded exercises called `alankard` for practicing raaga and tala, and he composed many songs specifically for learning purposes. This kind of a long-standing tradition of systematizing musical training may have contributed to the general South Indian receptivity to notation for educational purposes, if for no other purpose. In addition, a repertoire of songs such as varnam has provided a body of music that is relatively notatable.

` He was one of the first to devise graded exercises called `alankard` for practicing raaga and tala, and he composed many songs specifically for learning purposes. This kind of a long-standing tradition of systematizing musical training may have contributed to the general South Indian receptivity to notation for educational purposes, if for no other purpose. In addition, a repertoire of songs such as varnam has provided a body of music that is relatively notatable.

Notation is also a means of preservation, and the use of notation would presumably imply a desire for preservation. There is a strong desire in the south to know who composed what, and the composers themselves publish their compositions in notated form. In the Carnatic tradition, the composer, as distinguished from the performer is on the whole more significant (though the two may be the same also). In the North, there does not seem to be this desire to remember who composed songs. The sense of ownership of drum compositions seems to be stronger there than that of songs, and memory rather than notation is counted on as a means of preserving the compositions. This is probably another reason why far less music is notated in North than in South Indian classical music.

The degree of exactness implied by the term `notated` in Indian Classical music is quite different from what one would normally assume. One may find a melody notated and published in a collection in North India, but the notated form is unlikely to be the source from which a performer learned the melody. In fact, even if the performer has learnt from the notation, his performance of the same is bound to be quite different from the notated version. There is no particular desire to render songs as they had been originally composed or learned.

The notations of Carnatic Varna are more standardised. However, even in the case of Varna, the profuse ornamentation in performance style is an element supplied by the performer from his own knowledge rather than implied or written out in the notation. The Carnatic notations of Kriti are more like variants of a Western folk song. The performers publish their own variant of a song, and although two variants might be quite different, they are regarded as the same song.

It is for these and other reasons, melodies in notated form bear little resemblance to their realization in performance. The notation gives only a skeletal outline, paring the music to its melodic and rhythmic essentials.