About Indian Literature

History of Indian Literature caters the wide bifurcation between the ancient scriptures to the adapted colonial tongue, and the attempt of the empire writing back. Indian literature, through its umpteen legends and folklores in prehistoric times, is today unanimously recognised and acknowledged as one of the oldest in the world. India possesses twenty-two officially accredited languages and a colossal variety of literature has been produced and reproduced in these languages over the graduating years. It, thus, becomes evident that the history of Indian literature assimilates within itself an endless variety of untold stories and facts from ancient, medieval and comparatively modern times, which can be personified as a living entity.

History of Indian Literature caters the wide bifurcation between the ancient scriptures to the adapted colonial tongue, and the attempt of the empire writing back. Indian literature, through its umpteen legends and folklores in prehistoric times, is today unanimously recognised and acknowledged as one of the oldest in the world. India possesses twenty-two officially accredited languages and a colossal variety of literature has been produced and reproduced in these languages over the graduating years. It, thus, becomes evident that the history of Indian literature assimilates within itself an endless variety of untold stories and facts from ancient, medieval and comparatively modern times, which can be personified as a living entity.

Encompassing within the historical aspect, Indian literature lays considerable stress upon oral and written forms, both of which were the primary patterns of successive transmittance. As is known from ancient Indian history, Hinduism was the most predominating religious faction that ever ruled in pre-Christian era, thus inducing lasting impressions upon the literary scenario. As such, Hindu literary traditions dominated a sizeable part of Indian culture. Apart from the Vedas (comprising of Upanishads, Samhitas, Brahmanas and Aranyakas) which are considered to be the cardinal sacred form of knowledge, there also exists other scholarly works to fulfil this Hindu written and oral custom.

History of Indian literature comes about in a wholesome domain through the Hindu epics like Ramayana and Mahabharata, treatises such as Vaastu Shastra in architecture and town planning and Arthashastra by Kautilya (also admired as Chanakya), making political science and involvement in politics household in ancient India. Prehistoric devotional Hindu play, poetry and songs sweep the subcontinent, with almost distinct imagery noticed in the gradual evolvement of literature in India. Indeed, if looked into rather deeply, it can be noticed that history of literature in India can be smoothly divided into three periods, comprising of the ancient, the medieval and modern or contemporary. The period of the ancient Indian literature can be delineated by those very first orally transmitted (shruti) valuable treatises in the guru-shishya mode, which gradually were replaced and revived in the Vedic Period, denoting just the commencement of Golden Age in India, through Sanskrit literature. Second in line was to arrive the era of Medieval Indian literature, which witnessed a shift towards much more religious zealousness in regional divisions, although Sanskrit still was retained as the essential penmanship language. The Bhakti Movement was largely responsible for such a breakaway from the ancient `Golden Moments`. After considerable historical movements, inventions, discoveries, treatise-framing and near-wars concerning Indian literature, the time had come for indigene literature to witness its travel towards contemporary Indian literature. This phase was a significant time during the post-Christian era, which was to define the ideal metamorphosis of Indian rebellious writers and their fuming socialism in the umpteen Indian Independence movements and thereafter.

History of Indian literature comes about in a wholesome domain through the Hindu epics like Ramayana and Mahabharata, treatises such as Vaastu Shastra in architecture and town planning and Arthashastra by Kautilya (also admired as Chanakya), making political science and involvement in politics household in ancient India. Prehistoric devotional Hindu play, poetry and songs sweep the subcontinent, with almost distinct imagery noticed in the gradual evolvement of literature in India. Indeed, if looked into rather deeply, it can be noticed that history of literature in India can be smoothly divided into three periods, comprising of the ancient, the medieval and modern or contemporary. The period of the ancient Indian literature can be delineated by those very first orally transmitted (shruti) valuable treatises in the guru-shishya mode, which gradually were replaced and revived in the Vedic Period, denoting just the commencement of Golden Age in India, through Sanskrit literature. Second in line was to arrive the era of Medieval Indian literature, which witnessed a shift towards much more religious zealousness in regional divisions, although Sanskrit still was retained as the essential penmanship language. The Bhakti Movement was largely responsible for such a breakaway from the ancient `Golden Moments`. After considerable historical movements, inventions, discoveries, treatise-framing and near-wars concerning Indian literature, the time had come for indigene literature to witness its travel towards contemporary Indian literature. This phase was a significant time during the post-Christian era, which was to define the ideal metamorphosis of Indian rebellious writers and their fuming socialism in the umpteen Indian Independence movements and thereafter.

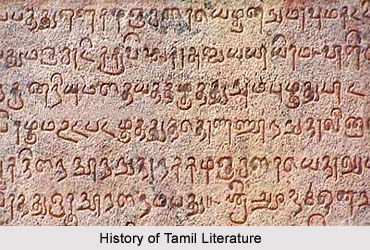

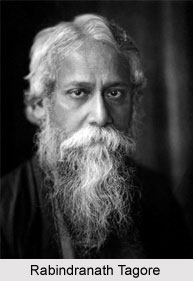

Among the best known works re-delineating history of Indian literature and its inherent involvement with present Indian scenario, Kalidasa and Tulsidas (legendary for his epic Hindi poem based on the Ramayana, named the Ramcharitmanas) top the ancient and medieval times. Tamil poetry of the `Sangam poetry`, which dates back to 1st century B.C.E., is also considerably celebrated it own right. Keeping Hindu literary customs aside from history of literature in India, Islamic influence perhaps comes second in the illustrious lineage of literary development. Indeed, the advent of Islam in India, through the Persian Silk Route, had brought in significant change of style in writing, speaking or preserving. During the medieval period, during which epoch India was mostly under Muslim rule, Indian Muslim literature flourished, most notably in Persian and Urdu poetry and prose. Descending a bit down towards modern times, amongst the contemporary Indian litterateurs, Rabindranath Tagore, an institution by himself, had become India`s first Nobel laureate for his poetic works in Gitanjali. A thing to feel extremely proud of, so far India`s premier literary honour, the `Jnanpith` awards, has been bestowed seven times upon Bengali writers, which is the highest for any language in India.

The history of Indian literature is the historical development of writings in prose or poetry, which aim at providing education, entertainment and enlightenment to its readers, as well the development of the literary techniques employed in the communication of these pieces.

History of Indian Literature on Buddhism

Buddhism as a sect has its roots in India. Led by Lord Buddha, this religion gained popularity in India. His teaching was Indian throughout. Buddhism is known to have left indelible marks on the social and cultural life of the people in different parts of India. It is important to note that Indian literature has glorified Buddhism and is also considered to be somewhat distinct and different from literature of other countries wherein Buddhism has flourished. Substance and form amalgamate with each other in any literary composition. This genius is perceived as flowing quietly and steadily, in spite of the almost imperceptible changes over the years and the ethos of the different epochs.

Buddhism as a sect has its roots in India. Led by Lord Buddha, this religion gained popularity in India. His teaching was Indian throughout. Buddhism is known to have left indelible marks on the social and cultural life of the people in different parts of India. It is important to note that Indian literature has glorified Buddhism and is also considered to be somewhat distinct and different from literature of other countries wherein Buddhism has flourished. Substance and form amalgamate with each other in any literary composition. This genius is perceived as flowing quietly and steadily, in spite of the almost imperceptible changes over the years and the ethos of the different epochs.

Indian Literature on Buddhism has been compiled by the great thinker, Rabindranath Tagore. He has penned about Bodhi, continued popularity of Buddha and his enlightenment. Bodhi is also known as enlightenment in English. Bodhi relates to ones true awakening and the revelation of infinite joy in us by the light of love. When the man is not completely conscious about the highest reality that surrounds him, he remains in a state of spiritual sleep and is confined within his own self. This is the state of avidya as he does not know about the reality of his own soul. It is the awakening from the sleep of self to the perfection of consciousness that leads to Bodhi or becoming the Buddha. As ones physical nature is set free in attaining health, social being is liberated in attaining goodness, similarly, ones own self gains independence in attaining love. Liberation of self by attaining love finally leads to extinction of selfishness. This extinction is the function of love, which leads to illumination. To become a light to oneself called Atmadipa is a teaching of Buddha. Those becoming a light to one self are also taught to help others to light their lamps, so that the darkness of sorrow gets removed which has engulfed humanity.

At Sarnath near Varanasi, it is known that Buddha converted five recluses to his new doctrine after his enlightenment. Within a span of three months, his followers increased to sixty. The teachings of Buddha had spread rapidly but peacefully during this time. After Buddha`s death, Buddhist councils wanted to ascertain the authenticity and priority of the available teachings of Buddha. It is the third council that settled the Buddhist canonical literature and grouped it under three divisions called the Tripitaka, after the Buddha`s parinirvana. Tripitaka means three pitakas or baskets. These divisions are the Vinaya Pitaka (the rules for the conduct of the order), the Sutta Pitaka (doctrines of the order), and the Abhidhamma Pitaka (higher subtleties of the doctrine). The Vinaya Pitaka comprises of the rules of discipline to be followed by the Buddhist Sangha and commands for regulating the daily life of monks and nuns. The Sutta Pitaka is a collection of the large and small doctrinal compositions. It is the primary source for the teachings of the Buddha and his earliest disciples. The Abhidhamma Pitaka consists of seven books, usually known as the Sattapakaranas. According to the Pali texts, this is what the Buddha taught the tavatimsa Gods and the Sariputta. It is important to note that the contents of Tripitaka do not highlight a systematic philosophy, but are considered to be a special treatment of the Dhamma as found in the Sutta Pitaka. The Dhammapada is an anthology containing 423 verses which is divided into 26 vaggas (chapters). The Buddhists believe that they are the very words of Buddha formulated to impart moral teachings to the common man.

Buddhism in Indian regional languages is known to be a vast subject. With the diversification of Buddhism, Buddhist literature also became dynamic. It is important to note that wherever Buddhism journeyed it got infused in the local culture. More specifically, this infusion took place on one hand by Buddhism itself adapting to local beliefs and cults and on the other hand ensuring the absorption of these beliefs and cults into its own system. Thus it can be said that geographical diffusion of Buddhism followed by its cultural adaptations, led to its diversity in India. Other factors giving impetus to this diversification were certain characteristics of Buddhism itself like the absence of a central doctrinal authority (the Catholic Church), the relation of the Buddhist Order with the temporal power, social stratification within the clergy and the royal patronage. Subsequently, these became the reasons for endangering the Buddhist literature in different regions and different languages of India. Thereafter, during the 19th century, Buddhism had established contact with the West which endowed it with better health in India. The hearts of Indian intellectuals were incited to act consequent to increasing interest of European scholars. Some scholars highlight, Migeltuwalte Gunanande`s dynamic role in the famous debate at Panadura in August 1873 which attracted outside scholars and created a stir. Later, the Theosophical Society helped in Buddhism"s revival after the visit of Col. Olcott and Madame Blavatsky and Ceylon in 1880 to India. Col. Olcott established the Buddhist Theosophical Society on June 17, 1880 in Colombo, with the help of Maha Theras.

In 1891, the birth of Mahabodhi Society by Anagarika Dharmapala is considered to be an exclusive contribution towards the resurgence of Buddhism within India as well as outside India. It is this society that took the responsibility of publishing Buddhist literature in English and Indian languages. It was also the time when Sir Edwin Arnold`s poem "The Light of Asia" came up and is known to widely influence modern Indian languages. This is evident in the adaptations of the poem in almost all major Indian languages. During the third century, Buddhists had launched a campaign against social evils like orthodoxy, static caste system and the privileges associated with it, ritualistic worships and other things, in different regions of India. Literature in regional languages was thus graced by the effect of this movement. History then highlights complete disappearance of Buddhism from India for many centuries, after which Buddhist literature resurrected. More specifically, the regional languages of India structured the Buddhist literature thereon. A noteworthy example is Visva-Bharati`s contributions to the enrichment of Buddhistic studies. More recently, Bhimrao Ramji Ambedkar is credited with creation of a new wave of Buddhism`s revival.

Focusing on South India, Buddhism died in Karnataka in the 12th century. It reached Kerala during the reign of Ashoka. Asan`s Karuna and Chandala Bhikshuki are based on Buddhistic doctrine. In Tamil Nadu, Buddhism was popular between the 5th and the 7th centuries and by the 14th century it had almost disappeared. Bimbisara Gathi is a Buddhistic work which was lost in this region. Siddhartattohai and Tiruppatikam are based on Buddhistic doctrine. In Tamil Nadu, Buddhism only lived in a few works of literature otherwise it had practically disappeared from the region. Andhra Pradesh was gracious to Buddhism, so Buddhist literature sheltered here, even during the modern period. The life of Buddha was compiled by twin poets Tirapati and Venkata Kavulu in verse form in Buddhacharita. Saundaranandam was written in verse by their pupils, Pingali and Katuri Kavulu. It depicts the story of Bodhisattva. The Light of Asia by Edwin Arnold`s was translated into Telugu verse under the title Pragjyoti. Some of the Telugu translations of Sanskrit Buddhist works are Samagamam, Karuna Sindhuvu, Mahabodhi, Dharma Gita.

Related Articles:

Religious Influence on Indian Literature

Tantra in Buddhism

Buddhism

Buddhism in India

Gautama Buddha

Buddhist Philosophy

Buddhist Literature

Indian Literature in Various Ages

Indian Literature in Various Ages has undergone tremendous transformations. Stark changes can be observed if the journey of Indian literature is traced from ancient times to contemporary age. Numerous great writers, who have emerged through ages, have enriched the Indian culture with amazing literary works. These compositions have played a crucial role transforming the society also with the incorporation of new ideas and concepts. The rich socio-cultural heritage of India has been appropriately depicted in the Indian literature.

Indian Literature in Ancient times

Indian Literature in Ancient times

Ancient Indian literature comprised of poetries, narratives, songs, religious texts and many more. Even in ancient times, there were many elements in the literature besides religious aspects of the country. The most well known ancient literature of India includes the Vedas which is composed of sacred texts for religious rituals and concepts. The texts are mythical where various interpretations of social and political structure of the society can also be found and the prose exhibit high literary value. Vedic poets, known as Rishi, had visualized the various aspects of life and the world which found brilliant expression through the poems of Vedas. Yajur Veda relates to creative reality, Rig Veda comprises of verses having archetypal meanings which have been moulded in different melodies in Sama Veda and Atharva Veda pertains to prosperity and peace in society. Literary works in ancient times also include the great epics namely Mahabharata and Ramayana. Ramayana, composed by poet Valmiki, has depicted the concept of the victory of good over evil whereas Mahabharata, written by Vyasa, describes the different layers of social and political life of ancient India. These highly acclaimed literary works have not only been translated to different regional languages but have also gained popularity across the world owing to their universal appeal.

Puranas

Puranas represent another phase of Indian literature where interpretations and explanations of the verses of Vedas can be found. The Puranas are composed of mythological stories and legends. Social, cultural and religious history of the country is very accurately illustrated through the Puranas. These cover five subjects namely

(1) Sarga, pertaining to creation of Universe.

(2) Pratisarga, which depicts the cycle of creation and destruction.

(3) Manvantara, where illustrations of various eras and cosmic styles can be found.

(4) Surya Vamsha and Chandra Vamsa relates to the history of dynasties of Gods and saints.

(5) Vamshanucharita which describes the lineages of Kings.

These five subjects form the focus of the various aspects of the society including sacrifices, customs, festivals, ceremonies, and pilgrims, descriptions of temples and rituals and duties of various castes.

Indian Literature in Sanskrit

Indian Literature in Sanskrit

Indian literature has also been enriched by many literary works in Sanskrit language. Sanskrit literature can be categorised as the Vedic and the Classical. The epics, Ramayana and Mahabharata, had acted as precursors of numerous poetries, dramas and many other compositions which covered many spheres like medicine, grammar, mathematics, astrology etc. The most prominent name in Sanskrit literature is Kalidasa who had written some of the greatest compositions. Kumarasambhava and Raghuvamsa are the two great epics composed by Kalidasa. Lyrical poetry is another notable feature of Sanskrit literature which was usually combinations of religious and erotic sentiments. Meghaduta is an excellent testament of lyrical poetry. Panchatantra, written by Vishnu Sharma, and Hitopadesha, written by Narayan Pandit, are other masterpieces of Sanskrit literature which deal with practical wisdom and politics.

Literature in Pali and Prakrit

After Vedic period, Pali and Prakrit were the most prevalent languages in India. In ancient India, these languages were adopted by Buddhists and Jains as sacred languages. The Jataka Kathas are one of the most famous Buddhist literary works which comprises of tales of formers births of Lord Budha. Religious doctrines of Buddhism are aptly propagated through these tales. Eminent literary works of Jains are also famous like the vast Katha written by Jain sages. Well known Jain poetesses are Mahavi, Roha, Pahai and Sasippaha.

Early Dravidian Literature of India

Early Dravidian Literature of India

Compositions in mainly four languages comprise the Dravidian literature, namely Malayalam, Kannada, Telugu and Tamil. Out of these languages, Tamil is the oldest and had most prominently retained the Dravidian characteristics. Ancient Tamil literature, also referred as Sangam literature, consisted of two schools of poet namely `asham` and `puram`. Asham were basically love poems whereas puram were poetries related to public and heroes. Vaishnava and Bhakti literature are other prominent literary works of this era which were related to Lord Vishnu and devotion respectively.

Indian Literature in Medieval Age

Modern languages started developing in India around 1000 A.D. Variations and deviations in ancient languages due to regional and ethnic influences led to this development. Devotional literature, also known as Bhakti literature, reached great heights during medieval era. Compositions in languages acceptable to common man became more and more popular. Different regional languages evolved and notable writers emerged offering some of the greatest literary works to the nation. In medieval period, Hindi literature also gained popularity and attracted even the regional poets like Guru Nanak (Punjabi) and Namdev (Marathi). Hindi literature reached its zenith through some of the masterpieces of writing by Tulsidas, Surdas and Meera Bai where Vaishnavite lyricism was most prominent. The religious and cultural aspects of Indian society were beautifully expressed through their works. Stupendous literary works in Bhakti literature have also been rendered by some women poets like Lopamudra, Apala, Gargi, Romasha Brahmavadini etc. Apart from Bhakti literature, heroic narrations and love ballads also spanned the Indian literature of medieval era. Hir Ranjha is one of the most amazing compositions in Punjabi. Urdu also started developing in this era and poets like Amir Khusro created some of the greatest works of Urdu literature. Different types of compositions having Persian and Iranian origin also enriched this literature and added more vigour to it.

Indian Literature in Modern Era

Indian Literature in Modern Era

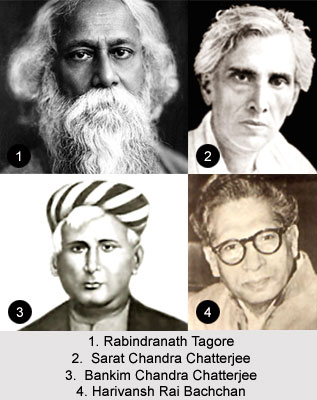

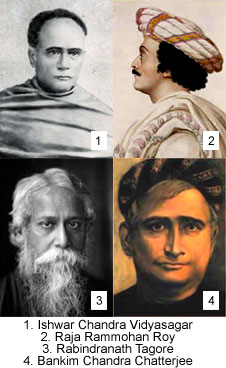

Indian literature in the modern era was influenced by a number of factors like Indian freedom struggle, effect of western culture and political consciousness among people. These had a combined effect on Indian literature which moulded it into different forms. Several ideologies were conveyed through writings by different poets who represented an amalgamation of Indian and Western culture. Concepts of writers took an arduous bent towards reformist, nationalistic and revivalist thinking. Bankim Chandra Chatterjee, U.Ve. Swaminatha Iyer, K.V. Pantulu, Vivekananda, Mahadev Govind Ranade, Narmada Shankar Lalshankar Dave and many other writers provided a new facet to the Indian literature. Composition in various modern as well as regional languages started to pave their way in the Indian society and with the advent of printing press, their propagation became easier. Evolution of journalism in the form of periodicals and newspapers played a crucial role in the development of prose for spreading new concepts and ideas in the society. Rabindra Nath Tagore, the world famous poet and Nobel laureate of the country incorporated the concepts of federalism and unity in diversity in Indian literature. Political saints like Kabir, Guru Nanak and Chaitanya also played important roles in spreading these concepts throughout the society.

Progressive Literature of India

During the India`s freedom struggle, many poets worked to bring about a new outlook in the society. They stirred the thought process of common man and evoked them to scrutinize their relationship with the society. Literary works in this era included compositions that threw light on the problems prevailing in the society like economic and social inequality and many more. Prominent writers and poets of this era are Manik Bandyopadhyay, Samar Sen, Vaikkom Muhammed Basheer, Shivaram Karanath etc. They composed masterpieces in different regional languages which included novels, poetries and fictional stories.

Contemporary Indian Literature

Post modern era comprised of contemporary literature. These works always tried to reach the common man. Contemporary literature has escaped from the traditional style of writing with social or philosophical teachings and created a new style which included simple narrations of tales and questioning any idea before accepting them. Eminent novelists of the contemporary age enlist Jayamohan (Tamil), Shivprasad Singh (Hindi), Debesh Ray (Bengali) and many more. However these novelists faced a great difficulty during the transition that they tried to inculcate in the society. The journey from the rural and traditional values to the path of modernization required a lot of effort. Some other writers who portrayed the new facet of Indian society are Birendra Kumar Bhattacharya (Assamese), Pannalal patel (Gujarati), Samaresh Basu (Bengali), Sunil Gangopadhyay (Bengali), Moni Manikyam (Telugu), Rajam Krishnan (Tamil) etc. The literary works of modern India also included sketches of real India, demolition of myths and harmonization concepts.

Indian Literature in Various ages has witnessed drastic changes in terms of concepts, ideas, narrations and interpretations. Several facets of it have emerged over time and no single language has been able to assimilate them all. In fact, compositions in different languages are intertwined with each other which share common themes, forms and directions. These have helped in maintaining the dynamism of Indian literature. Several classics of Indian literature are highly acclaimed all over the world.

Marxism in Indian Literature

Marxists always have stood by the faith that economic and social circumstances have been forever determining one`s religious beliefs, the nation`s legal systems and a society`s cultural frameworks. They are also of the view that `art` and the aesthetic world should not only exemplify such conditions truthfully, but also seek to make them better. Such Marxist view of aesthetics is not although quite prospering in today`s consumerist society, but stays on to enquire about responsible questions. Such high-flowing and ambitious thoughts, however was not just built in a day; it did take a lot more of the most historical brains to make Marxism what it is today. Marxism is the political doctrine and practice, that has been derived from the works of Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels. "Marxism" essentially represents an economic political theory, under which the eye of law is considered a tool of tyranny and dominance and which the "ruling class" - the heavyweights in power - utilises against the "proletariat" - the blue-collared servants. Marxism holds in its heart of hearts an analytical evaluation of `capitalism` and a theory of vast social metamorphosis. The potent, fierce and innovatory analytical methods Marx had inaugurated, have influenced down the line an all-embracing range of disciplines. The 20th and 21st centuries have had exerted sufficient influence and charm upon the erstwhile Marxist approaches, which further have made their theoretical presence felt in the Eastern and Western academic fields, comprising: archaeology/anthropology, media studies, political science, theatre, history, sociological theory, education, economics, literary criticism, aesthetics, critical psychology and philosophy. Indeed, with Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels being two men from the west, did not just stop India from being captivated and enamoured with the principles that have just been described above. Leaving out the socialist, economic and political fronts, Marxism is that domain which was tremendously propagated in India through the field of Indian literature. Truly, as can be witnessed later, Marxism in Indian literature has been quite profound and distinctive in the strong hands of master men.

Marxists always have stood by the faith that economic and social circumstances have been forever determining one`s religious beliefs, the nation`s legal systems and a society`s cultural frameworks. They are also of the view that `art` and the aesthetic world should not only exemplify such conditions truthfully, but also seek to make them better. Such Marxist view of aesthetics is not although quite prospering in today`s consumerist society, but stays on to enquire about responsible questions. Such high-flowing and ambitious thoughts, however was not just built in a day; it did take a lot more of the most historical brains to make Marxism what it is today. Marxism is the political doctrine and practice, that has been derived from the works of Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels. "Marxism" essentially represents an economic political theory, under which the eye of law is considered a tool of tyranny and dominance and which the "ruling class" - the heavyweights in power - utilises against the "proletariat" - the blue-collared servants. Marxism holds in its heart of hearts an analytical evaluation of `capitalism` and a theory of vast social metamorphosis. The potent, fierce and innovatory analytical methods Marx had inaugurated, have influenced down the line an all-embracing range of disciplines. The 20th and 21st centuries have had exerted sufficient influence and charm upon the erstwhile Marxist approaches, which further have made their theoretical presence felt in the Eastern and Western academic fields, comprising: archaeology/anthropology, media studies, political science, theatre, history, sociological theory, education, economics, literary criticism, aesthetics, critical psychology and philosophy. Indeed, with Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels being two men from the west, did not just stop India from being captivated and enamoured with the principles that have just been described above. Leaving out the socialist, economic and political fronts, Marxism is that domain which was tremendously propagated in India through the field of Indian literature. Truly, as can be witnessed later, Marxism in Indian literature has been quite profound and distinctive in the strong hands of master men.

Marxism in Indian literature was first noticed during the Indian Independence Movement, when the theories of Communism and Socialism had entered the pre-Independent scenario in an overwhelming manner. The arrival of the 20th century in India, severely oppressed under the British, was also that period during which the concept of the "middle class" had arose, with every household including a man, who was fuelled with the principle to lash out against the tyrannical government and everything that was being imposed by such an administration. And the British Indian set-up was just perfect to have provided a platform thus. Even the higher section of society had joined in this crusade of the proletariat and this "brave, angry young man" image was mostly mirrored and manifest through the most-accepted field of literature. With the tremendous and passionate propagation of pamphlets, newspapers, evening dailies, essays, articles in the short literary section and drama, poetry and short stories in the broader and more extensive section, Indian literature was doused in Marxism at a point of time, during which Marathi, Urdu, Hindi and of course, Bengali literature had come to most view and mass light.

Marxism in Indian literature was first noticed during the Indian Independence Movement, when the theories of Communism and Socialism had entered the pre-Independent scenario in an overwhelming manner. The arrival of the 20th century in India, severely oppressed under the British, was also that period during which the concept of the "middle class" had arose, with every household including a man, who was fuelled with the principle to lash out against the tyrannical government and everything that was being imposed by such an administration. And the British Indian set-up was just perfect to have provided a platform thus. Even the higher section of society had joined in this crusade of the proletariat and this "brave, angry young man" image was mostly mirrored and manifest through the most-accepted field of literature. With the tremendous and passionate propagation of pamphlets, newspapers, evening dailies, essays, articles in the short literary section and drama, poetry and short stories in the broader and more extensive section, Indian literature was doused in Marxism at a point of time, during which Marathi, Urdu, Hindi and of course, Bengali literature had come to most view and mass light.

Mahatma Gandhi was a key turning point and decisive factor to the first uprisings of the introduction of Marxism in Indian literature. Prior to the Second World War, the First World War had laid the foundation stone in Indian literature and the pre-Independent society in general, which was most intense in Maharashtra, particularly in Bombay, which was to some extent spearheaded by Gandhiji. A brief history is however required however in this regard. Industries in Maharashtra had begun to grow on a large scale during the First World War. The labour class had come into existence already. Simultaneously, the Indian Communist Party was established in 1925 and the labour movement had begun to strike roots. The new Marxist Philosophy put forward a fascinated aspect for the then native youth. However, this did not help create a progressive literary movement during that time. The influence of Marxism did not extend beyond the delineation of occasional disagreements between the rich and the poor, slogan shouting by the hero about `total revolution` and deriding down the tradition-loving class as `the bourgeoisie`. The novels of P. Y. Deshpande (1899-1986), V. S. Khandekar (1898-1976), V. V. Hadap (1900-60), G. T. Madkholkar (1899-1976) and the poems of Kusumagraj, Anant Kanekar (1905-80) and V. R. Kant (b. 1913) reflect the influence of Marxism upon Indian literature to a certain extent.

Beyond the regional restriction of Marxism in the field of Indian literature, the later periodical and rather more instigated seeds of this political philosophy of the "brave new world" were next witnessed during the period of Second World War, when the exposure to Marxism was most profound. The political situation in Germany, the fact that they were, for the most part, students, and their aspiration to become writers - everything contributed in varying degrees to a sense among them that they should form some sort of literary association. Writing was under all likelihood, the only avenue left open to the young guns - "Most of the members of our small group wanted to become writers, What else could they do? We were incapable of manual labour. We had not learnt any craft and our minds revolted against serving the imperialist government. What other field was left?" Such was the statement given by Sayed Sajjad Zaheer, the most influential and capable a man, who was the recognised and venerated face behind the establishment of the All-India Progressive Writers` Association (AIPWA). Indeed, AIWPA was that daring and intimidating literary organisation, which had spearheaded almost all the Marxist-oriented literary activities in the Indian subcontinent.

Beyond the regional restriction of Marxism in the field of Indian literature, the later periodical and rather more instigated seeds of this political philosophy of the "brave new world" were next witnessed during the period of Second World War, when the exposure to Marxism was most profound. The political situation in Germany, the fact that they were, for the most part, students, and their aspiration to become writers - everything contributed in varying degrees to a sense among them that they should form some sort of literary association. Writing was under all likelihood, the only avenue left open to the young guns - "Most of the members of our small group wanted to become writers, What else could they do? We were incapable of manual labour. We had not learnt any craft and our minds revolted against serving the imperialist government. What other field was left?" Such was the statement given by Sayed Sajjad Zaheer, the most influential and capable a man, who was the recognised and venerated face behind the establishment of the All-India Progressive Writers` Association (AIPWA). Indeed, AIWPA was that daring and intimidating literary organisation, which had spearheaded almost all the Marxist-oriented literary activities in the Indian subcontinent.

The first All-India Progressive Writers` Conference was held in Lucknow on April 10, 1936. The choice of place and the date for the Conference bore much significance in association with the influence of Marxism in Indian literature and its pan-Indian literary circuit. In April the annual meeting of the All-India National Congress was scheduled to be held in Lucknow and Pandit Jawahar Lal Nehru had been chosen to preside over its sessions. This was the period of the United Front and Soviet diplomacy had boosted foreign communist parties to enter into anti-fascist alliances. Within the Congress, Jawahar Lal Nehru was the leader of the left-wing and Sayed Sajjad Zaheer was had invited him to address the AIPWA Conference. In his speech, Nehru had indicated his warm backing for the Conference; Sarojini Naidu, a well-known Congress leader and poet, had sent the Conference a message of solid encouragement and support. Other outstanding leftist leaders including Jai Prakash Narain, Yusuf Mahraly, Indulal Yajnik, Kamla Devi Chattopadhay and Mian Iftakhar-Ud-Din had participated in the Progressive Writers` Conference. However, the number of literary delegates was not much extraordinary; only two from Bengal, three from Punjab, one from Madras, two from Gujarat, six from Maharashtra and twenty-five from Uttar Pradesh had trudged long distances to the Conference.  Of all the 25 Uttar Pradesh delegates, not one had represented Hindi writers. Well-known Hindi writers - Babu Maithili Sharan Gupta, Pandit Banarsi Das Chaturvedi, Sumitra Nandan Pant, Subhadra Kumari Chouhan, Pandit Bal Krishnan Sharma - had indicated mild recognition of the new Marxist-adhering literary movement, but had declined to attend the conference. The absence of Hindi writers was handsomely compensated by the presence of Munshi Prem Chand, who had agreed to preside over the AIPWA Conference. No one however had considered Prem Chand as a Marxist. Munshi Prem Chand had nevertheless represented the life of the Indian peasant in his novels, with deep discernment and compassion for his poverty and suffering, his superstitions and weaknesses.

Of all the 25 Uttar Pradesh delegates, not one had represented Hindi writers. Well-known Hindi writers - Babu Maithili Sharan Gupta, Pandit Banarsi Das Chaturvedi, Sumitra Nandan Pant, Subhadra Kumari Chouhan, Pandit Bal Krishnan Sharma - had indicated mild recognition of the new Marxist-adhering literary movement, but had declined to attend the conference. The absence of Hindi writers was handsomely compensated by the presence of Munshi Prem Chand, who had agreed to preside over the AIPWA Conference. No one however had considered Prem Chand as a Marxist. Munshi Prem Chand had nevertheless represented the life of the Indian peasant in his novels, with deep discernment and compassion for his poverty and suffering, his superstitions and weaknesses.

It can be quite comprehended by now that the period within the Partition of India of 1947 and the beginning of the reorganisation of the states within the new geographical boundaries of India will be remembered for two reasons in the history of Indian literature and its connection with Marxism and the Marxist principles of life. First, there was witnessed a growth of new literature out of the experience of partition, i.e. the Marxist literature within the framework of Oriental Indian literature. Second, there was also a growth of a new literature from the sense of fulfilment that the Independence had ushered in. Most unfortunately, that `fulfilment` was short lived. It had become a part of a larger experience of disillusionment as well as hope created by the changed political situation. The Indian Independence on 15th August, 1947 had brought in a sudden overriding sensing of emancipation and perfect and idyllic liberation from the imperialist tyranny, which was outstandingly mirrored in literature. However, this was just a momentary phase of happiness; the joy and hope of freedom had turned into unexpected disillusionment and frustration. The bleak and breakdown economy and its greater disorderliness and gloom in the country, the failure of the Congress and the decline of moral values, poverty, unemployment, social inequality and political corruption had begun to be once again upheld in Indian literature. And the essential balm and soothing consolation was once more provided through espousing Marxism, which was the true last resort of the writers who wished to voice out their hopelessness in every sphere of society. Marxism in Indian literature once more had begun to take its dramatic turn during the budding nation`s flowering and a looking forward towards an unsure future.

Bengali literature, mostly Bangla poetry and poetic verses had come to light during this rather metamorphosing phase, with other literary forms also assisting the writers. Authors from this period had outlived and survived the Independence and had considered themselves unlucky and misplaced in such a time, when the country was mostly once again disintegrating. Yet, at a more mundane level, the narratives of political struggles had projected the possibilities of a new society and had generated hope and conviction. The Bengali poems of Subhash Mukhopadhay (Agni Kon, 1948) and of Sukanta Bhattacharya (Chad Patra, 1948), both Marxists, had articulated the determined voice of revolution. The silver lining of hope visible amidst this sinister grimness was the ideology inciting people to change the existing social order, i.e., indeed by the all-encompassing and accepted predominance of Marxist influence in Indian literature, precisely in Bengali literature and its poetry. The Marxist writers had extended their influence to a remarkable extent. Subhash Mukhopadhay although had made his mark on Bengali poetry in the early years of 1940s, he had matured into an artist in the 1950s. Sukanta Bhattacharya, who had expired in 1947, had turned into idol of the younger generation and had dominated Bengali poetry with his fresh approach and exuberance. The Marathi poets with pronounced Marxist inclination, Sharatchandra Muktibodh and Vinda Karandikar and the Malayalam poet Vayalar Rama Varma, the most admired poet of social revolution, whose Kontayum punulum had appeared in 1950, have one thing in common - "robust optimism". The finest and the most illustrious work of this period, demonstrating the hold of Marxism in Indian literature, a work that had articulated the voices of the oppressed and had projected the dream of a social order free of exploitation and tyranny is the epoch-making Telugu poem Mahaprasthanam (1950) by Sri Sri. Narrative literature too had fearlessly upheld the struggle of the oppressed. Kishan Chand had portrayed the heroic uprising in Telengana, in his Ajanta Ke Age (1948) and Jab Khet Jage (1952). Most of the writings of Yashpal, Nagarjun and Rahul Sankrityayan, all of them penning in Hindi, also had shared an optimism and vision of a new society. Hence, Marxism and its control upon Indian literature, with particular stress upon the post-Independent India was most profound, which with time, has gained its generic foothold, to be remembered for centuries to come.

Bengali literature, mostly Bangla poetry and poetic verses had come to light during this rather metamorphosing phase, with other literary forms also assisting the writers. Authors from this period had outlived and survived the Independence and had considered themselves unlucky and misplaced in such a time, when the country was mostly once again disintegrating. Yet, at a more mundane level, the narratives of political struggles had projected the possibilities of a new society and had generated hope and conviction. The Bengali poems of Subhash Mukhopadhay (Agni Kon, 1948) and of Sukanta Bhattacharya (Chad Patra, 1948), both Marxists, had articulated the determined voice of revolution. The silver lining of hope visible amidst this sinister grimness was the ideology inciting people to change the existing social order, i.e., indeed by the all-encompassing and accepted predominance of Marxist influence in Indian literature, precisely in Bengali literature and its poetry. The Marxist writers had extended their influence to a remarkable extent. Subhash Mukhopadhay although had made his mark on Bengali poetry in the early years of 1940s, he had matured into an artist in the 1950s. Sukanta Bhattacharya, who had expired in 1947, had turned into idol of the younger generation and had dominated Bengali poetry with his fresh approach and exuberance. The Marathi poets with pronounced Marxist inclination, Sharatchandra Muktibodh and Vinda Karandikar and the Malayalam poet Vayalar Rama Varma, the most admired poet of social revolution, whose Kontayum punulum had appeared in 1950, have one thing in common - "robust optimism". The finest and the most illustrious work of this period, demonstrating the hold of Marxism in Indian literature, a work that had articulated the voices of the oppressed and had projected the dream of a social order free of exploitation and tyranny is the epoch-making Telugu poem Mahaprasthanam (1950) by Sri Sri. Narrative literature too had fearlessly upheld the struggle of the oppressed. Kishan Chand had portrayed the heroic uprising in Telengana, in his Ajanta Ke Age (1948) and Jab Khet Jage (1952). Most of the writings of Yashpal, Nagarjun and Rahul Sankrityayan, all of them penning in Hindi, also had shared an optimism and vision of a new society. Hence, Marxism and its control upon Indian literature, with particular stress upon the post-Independent India was most profound, which with time, has gained its generic foothold, to be remembered for centuries to come.

Indian Literature after Independence

Indian Literature after Independence of the country witnessed some major changes in terms of literary writings. Indian independence may be a historic event for its socio-political significance. But according to some writers, this event has had an outstanding impact on the creative writing done in various regional languages of the writers. India`s nationalism at the point before independence was a nationalism of grief and mourning. Thus, most of the new age writers through their writings portrayed the terrible fake world that was based on the western modernism. However, in a country like India, the vast culture of the past does not go off completely. With the independence of the country the cultural rhythm of the past certainly broke down as a result of modernistic experimentations. Rabindranath Tagore, Sarat Chandra Chatterjee, Vallathol Narayana Menon, Munshi Premchand, Mardhekar and Iqbal, to mention a few towering peaks in the Indian literary scene in the first half of this century, had given their best before independence.

Indian Literature after Independence of the country witnessed some major changes in terms of literary writings. Indian independence may be a historic event for its socio-political significance. But according to some writers, this event has had an outstanding impact on the creative writing done in various regional languages of the writers. India`s nationalism at the point before independence was a nationalism of grief and mourning. Thus, most of the new age writers through their writings portrayed the terrible fake world that was based on the western modernism. However, in a country like India, the vast culture of the past does not go off completely. With the independence of the country the cultural rhythm of the past certainly broke down as a result of modernistic experimentations. Rabindranath Tagore, Sarat Chandra Chatterjee, Vallathol Narayana Menon, Munshi Premchand, Mardhekar and Iqbal, to mention a few towering peaks in the Indian literary scene in the first half of this century, had given their best before independence.

Post-independence India did see greater awareness on the part of the reading public as well as the government of the existence of many more and richer languages and literatures, beyond the limited periphery of one`s own mother-tongue or province. Some states entered a big way by giving prizes and awards and much translation work was encouraged. Writers received the opportunity of visiting new places and publicise their works. All this, with all its limitations, did stimulate a literary climate. Further, the industrial and scientific advancement throughout the country after independence also had an impact on Indian literature. In spite of the new vistas opened to the writers in the form of writing for the new mass media like the film, the Radio and TV, the character of Indian literature continues to remain feudal, romantic, pastoral, idyllic and medievalist. Interestingly, the post independence literature of the country showed signs that permanent literature springs out of great tragedy.

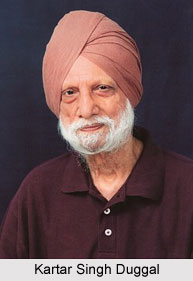

The partition of India did sear a poignant scar in the souls of many writers, particularly in Punjabi literature, Urdu literature, Hindi literature, and Bengali literature. Many moving short stories and poems have been written on this subject by authors like Amrita Pritam, Kartar Singh Duggal, Krishan Chander, Khushwant Singh, Premendra Mitra and Manoj Basu, to mention a few names. The martyrdom of Mahatma Gandhi was another such event, about which soul-stirring poems were written by Vallathol Narayana Menon, Wamiq Jaunpuri, Bhai Vir Singh, Shivmangal Singh Suman and others. Hardly there was any mentionable little classic produced during this period. Some progressive critics oversimplify the situation by saying that the Indian writer comes from the lower middle-class, which is facing several physical and financial hurdles. One of the functions of literature is to elevate but nothing seemed to inspire them. But after 1948 there were several tragic events, but hardly any great literary piece was written. It was commonly believed that Indian independence did not bring any special bloom in the meadow or the field of literature. There were many successful novels written before the independence of the country, which won Sahitya Akademi Awards, and were even translated in English and Russian and several other languages. An identity crisis developed among the writers and poets of the fifties and sixties, the age considered as `dark modernism`. The particular identity crisis of the writers and the clash between traditional cultures and western modernity is mostly found in the writings during those days. The concept of experimentation also developed under the western influence. It emerged as a chase for new values and their sources.

The partition of India did sear a poignant scar in the souls of many writers, particularly in Punjabi literature, Urdu literature, Hindi literature, and Bengali literature. Many moving short stories and poems have been written on this subject by authors like Amrita Pritam, Kartar Singh Duggal, Krishan Chander, Khushwant Singh, Premendra Mitra and Manoj Basu, to mention a few names. The martyrdom of Mahatma Gandhi was another such event, about which soul-stirring poems were written by Vallathol Narayana Menon, Wamiq Jaunpuri, Bhai Vir Singh, Shivmangal Singh Suman and others. Hardly there was any mentionable little classic produced during this period. Some progressive critics oversimplify the situation by saying that the Indian writer comes from the lower middle-class, which is facing several physical and financial hurdles. One of the functions of literature is to elevate but nothing seemed to inspire them. But after 1948 there were several tragic events, but hardly any great literary piece was written. It was commonly believed that Indian independence did not bring any special bloom in the meadow or the field of literature. There were many successful novels written before the independence of the country, which won Sahitya Akademi Awards, and were even translated in English and Russian and several other languages. An identity crisis developed among the writers and poets of the fifties and sixties, the age considered as `dark modernism`. The particular identity crisis of the writers and the clash between traditional cultures and western modernity is mostly found in the writings during those days. The concept of experimentation also developed under the western influence. It emerged as a chase for new values and their sources.

Even disillusionment creates great literature. Various reasons have been cited behind the production of any good work after independence. The first reason for no great work in the creative field was that the writer, being in a period of transition between the traditional and the experimental, was not able to sift and choose and to properly discriminate between the deadwood and the living from the past. The second reason was the constant search for a new idiom. In a way, all the languages were not fully developed, yet they possessed a rich untapped reservoir in their classics. However, the creative writer`s frustrations in translating poetry from any foreign language into Indian language are worth taking to consideration. Thirdly, the Indian authors lacked identity crisis. One of the greatest impediments in the way of the growth of indigenous literature of India after independence was the dominance of double-standards.