About Vande Mataram

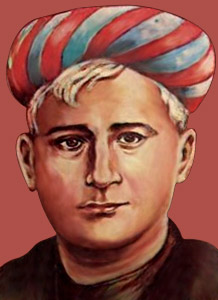

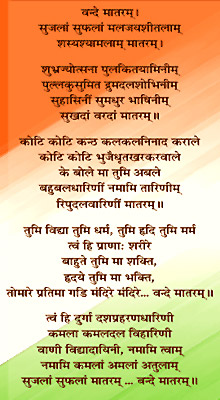

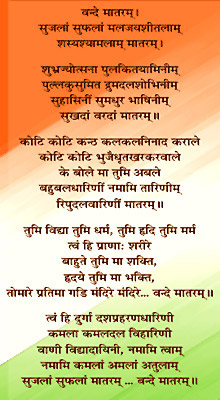

`Vande Mataram`, these two words impresses upon every Indian as the most blood-boiling, resounding and haunting word ever to be used in Indian independence movement and `swaraj`. The tremendous outcry of  Vande Mataram in the innumerable crusading voices, perhaps had touched every Indian sitting back in their homes with a different view to life. Quite naturally, this magical term goes long back in history, with an illustrious lineage of production. This was and still is considered the national song of India, bearing a distinctness of itself, quite different from the national anthem of India "Jana Gana Mana". The Vande Mataram song was composed by Bankim Chandra Chatterjee in a special dialect of Bengali and Sanskrit. The Indian National Congress session of 1896 was the first political instance where this song was sung.

Vande Mataram in the innumerable crusading voices, perhaps had touched every Indian sitting back in their homes with a different view to life. Quite naturally, this magical term goes long back in history, with an illustrious lineage of production. This was and still is considered the national song of India, bearing a distinctness of itself, quite different from the national anthem of India "Jana Gana Mana". The Vande Mataram song was composed by Bankim Chandra Chatterjee in a special dialect of Bengali and Sanskrit. The Indian National Congress session of 1896 was the first political instance where this song was sung.

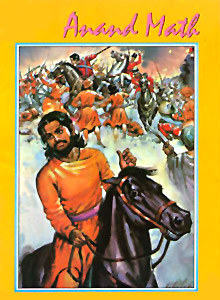

The song Vande Mataram was, on the one hand, popularly acclaimed as India`s national song and on the other, it has given rise to intense contestation on account of objections raised on the ground of its imagery and rhetoric and an implicit idolatry. Written sometime during the early 1870s, the original version, a lyrical vandana, or hymn, remained unpublished for some years. In 1881, Vande Mataram was included in the novel Anandamath. In an expanded version the poem was endowed with militant Hindu accoutrement in the context of the novel. Thus Bankim Chandra Chatterjee created a new icon, the motherland.

The popularity of Vande Mataram supported in the construction of Indian national identity. The slogan Vande Mataram has been widely acknowledged to bring Vande Mataram, the song into the forefront. The historical association of Vande Mataram with the nationalist movement gradually made it `a living and inseparable part of the nationalist movement` whilst portraying the popularity of Vande Mataram. It is therefore undeniable that Vande Mataram`s widespread appeal and popularity and its hold on public sentiment is still unprecedented.

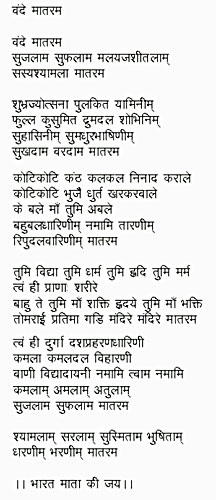

The imagery used in Vande Mataram further supported the popularity of the song. The poem Vande Mataram had been a lyrical ode to the motherland, `giver of bliss, richly watered and richly fruited, clad in blossoming foliage, sweet of laughter, sweet of speech` and strong in having seventy million sons to defend her. This can somewhat account for the tremendous popularity of Vande Mataram down the ages.

In 2003, BBC World Service carried on an international poll to choose ten most celebrated songs of all time. Approximately 7000 songs qualified in the selections from around the world. According to BBC, people spanning 155 countries and island voted Vande Mataram as second amongst the top 10 songs.

History of Vande Mataram, Indian National Song

History of Vande Mataram appears to be indeed diversified and highly unlikely, when one considers the time when it was written. It generally took ages for such kind of a song or prose or verse to achieve wide acceptance. It is normally believed that the concept of Vande Mataram dawned on Bankim Chandra Chatterjee when he was still serving as a government official under the British Empire. He wrote the song in an unprompted zeal, making use of words from Sanskrit and Bengali, two languages in which he excelled. However, the song was met with intense initial criticism, due to the obscurity in pronunciation of some of the words. The song first appeared in Bankim Chandra`s respected book Anandamath (pronounced Anondomô?h in Bengali), published in 1882. However, it saw the light of the day amidst fears of being banned by the English. Although, the song was actually penned down in 1876. Jadunath Bhattacharya composed the tune for Vande Mataram, just after it was written.

The history of "Vande Mataram" unfurls that it was an emblem of national outcry for freedom from British tyranny during the Indian freedom movement. Enormous rallies, gradually taking up the shape of a storm were initiated primarily in Bengal. The major metropolis of Calcutta, would bolster themselves up into a patriotic vehemence by crying out the slogan "Vande Mataram", or "Hail to the Mother (land)!". British very much dreaded the potentiality of imminent danger of an instigated Indian populace. At one point, they put a ban on the utterance of the motto in public forums and jailed innumerable freedom fighters for disobeying the prohibition. In fact, history of Vande Mataram becomes even more varied and exudes a feel of pride, when Rabindranath Tagore sang Vande Mataram in 1896 in the Calcutta Congress Session held at Beadon Square. Legends followed. Dakhina Charan Sen sang it five years later in 1901, during another session of the Congress at Calcutta. Poet Sarala Devi Chaudurani sang the song in the Benaras Congress Session in 1905. Lala Lajpat Rai started a journal called Vande Mataram from Lahore. Hiralal Sen made the first political film in India in 1905, which concluded with the hypnotic chant. Matangini Hazra`s last words as she was shot to death by the Crown police were Vande Mataram.

The history of "Vande Mataram" unfurls that it was an emblem of national outcry for freedom from British tyranny during the Indian freedom movement. Enormous rallies, gradually taking up the shape of a storm were initiated primarily in Bengal. The major metropolis of Calcutta, would bolster themselves up into a patriotic vehemence by crying out the slogan "Vande Mataram", or "Hail to the Mother (land)!". British very much dreaded the potentiality of imminent danger of an instigated Indian populace. At one point, they put a ban on the utterance of the motto in public forums and jailed innumerable freedom fighters for disobeying the prohibition. In fact, history of Vande Mataram becomes even more varied and exudes a feel of pride, when Rabindranath Tagore sang Vande Mataram in 1896 in the Calcutta Congress Session held at Beadon Square. Legends followed. Dakhina Charan Sen sang it five years later in 1901, during another session of the Congress at Calcutta. Poet Sarala Devi Chaudurani sang the song in the Benaras Congress Session in 1905. Lala Lajpat Rai started a journal called Vande Mataram from Lahore. Hiralal Sen made the first political film in India in 1905, which concluded with the hypnotic chant. Matangini Hazra`s last words as she was shot to death by the Crown police were Vande Mataram.

In 1907, Madam Bhikaji Cama (1861-1936) exhibited the first version of India`s national flag (the Tiranga) in Stuttgart, Germany in 1907. The flag was engraved with Vande Mataram in the middle band.

Bankim Chandra was a man of mystery and his historical evolvement of the song provides some dichotomy. It is not known for certain when the poem Vande Mataram was composed by Bankim Chandra Chatterjee. All that comes to light is that it probably took form in his mind over a long period, between 1872 and 1875. The first few verses of the poem, including the part now known as a national song, were written long before it was published in the novel Anandamath. In the memoirs written by Bankim`s younger brother it has been recounted that the poem had been lying around for several years in Bankim Chandra`s study. One of the assistants who helped him in editing a literary journal picked up the poem and commented that Vande Mataram would not be so bad and would in fact do quite well as a filler to fill up an empty space in the galley-proofs for the number. History of Vande Mataram seems quite like an ordinary story, when one considers it in the Indian Independence rank. Bankim Chandra, his nephew explained later, refused to have it published in that fashion and said, `You can`t possibly guess now if this is good or bad. Time will tell-I shall be dead by then, it is possible that you may see that day.` That was the end of the matter and the poem as one knows remained unpublished. Till one day Bankim Chandra went back to the poem he had written years ago to make it the centrepiece of a complex mosaic of ideas, the novel Anandamath.

From historical internal evidence however it appears that the first few verses of Vande Mataram were written after 1872. The ninth line of the song described the land, personified in `the Mother` saluted in the poem, as `awesome with the clamorous hail (to the Mother) from the throat of seven crores`. The number seven crore, or seventy million, was the population of the eastern part of the Indian subcontinent, the area under the lieutenant governor of Bengal; it then included the present states of Bihar and Jharkhand, Orissa, West Bengal, Assam and present-day Bangladesh. This figure, seven crore, was unknown till the first census in that part of India in the year 1871. Bankim Chandra wrote an essay in 1872 on the population statistics of the census of 1871. The poem could not have been written before 1872, i.e. before the publication of the census of population of eastern India.

Another kind of evidence regarding Vande Mataram`s history is the similarity of ideas between an essay written by Bankim Chandra in 1874 and the song Vande Mataram; numerous ideas and imageries are common between these two pieces of writing, leading to the hypothesis that they were written about the same time. A third piece of evidence is the testimony of Aurobindo Ghosh, later known as Sri Aurobindo of Pondicherry. Aurobindo writes in April 1907: `It was thirty-two years ago that Bankim wrote his great song....` Aurobindo Ghosh belonged to the generation next to Bankim`s and could have had access to people who knew the author well. He states very precisely that the poem was written in 1875. On the whole, it appears that the composition of the poem can be dated between 1872 and 1875.

From then till 1881 the poem did not see the light of day. In that year Bankim published it as a part of the novel Anandamath in the literary journal he edited. History of Vande Mataram takes an interesting turn from here. A notable fact is that when the poem was inserted in the novel and serialised in the journal, the first twelve lines (the first two stanzas) were put within quotation marks; the rest of the poem was printed without quotation marks. The reason for it has been rightly inferred that the author wanted to separate the first two stanzas which he had written earlier, around 1875, from the part written later (lines 13 to 27); the latter part was put outside quotation marks. The latter part was written probably in 1881 bearing in mind the context of Anandamath. This distinction between the originally composed song and the additions made later to fit into the narrative of the novel is important, because it was the latter part which contained those explicitly Hindu and idolatrous imageries which were objected to by many outside the Hindu community.

From the above-mentioned accounts, it becomes quite evident that, whatever the controversy or belief might be about the song, the history of Vande Mataram took an elevated status, owing to its billowing popularity in the pre-independence setting.

Vande Mataram in Pre-independent Society

Vande Mataram in pre-independent society can be referred as the most substantial phrase, which defined Indian toil and pain to achieve freedom. These two words, given shape by Bankim Chandra Chatterjee, in the times of late 19th century governs and explains the times prior to 1947, at times, ridden with internal trouble. People not only had to deal with huge political issues, but also became divided in their views in a course of time. The 20th century reflects the most concentrated historical period, when Vande Mataram assumed international renown. From 1905 the song Vande Mataram became a slogan for the nationalists. Many nationalist revolutionaries themselves preferred to call it their `mantra`. Aurobindo Ghosh writes in 1907 that it was a mantra of a new `religion of patriotism` given to the nation by `Rishi` Bankim Chandra Chatterjee.

It was thirty-two years ago that Bankim Chandra wrote his great song and few listened. Vande Mataram in pre-independent society was not wholly accepted in the beginning. The highly instigating song needed to be taken out from the closet, just waiting to be distributed among the crusaders. But in a sudden moment of awakening from long delusions, the people of Bengal looked round for the truth and in a fated moment somebody sang Vande Mataram. The mantra had been given and in a single day a whole people had been converted to the religion of patriotism. The Mother had revealed herself.

It was thirty-two years ago that Bankim Chandra wrote his great song and few listened. Vande Mataram in pre-independent society was not wholly accepted in the beginning. The highly instigating song needed to be taken out from the closet, just waiting to be distributed among the crusaders. But in a sudden moment of awakening from long delusions, the people of Bengal looked round for the truth and in a fated moment somebody sang Vande Mataram. The mantra had been given and in a single day a whole people had been converted to the religion of patriotism. The Mother had revealed herself.

Aurobindo Ghosh was not the first person to popularise the song, but he was the first to discern a peculiar significance in the religious semiotics of the song. Among the `rishis` one needs to include the name of the man who gave the reviving mantra which is creating a new India, the mantra Vande Mataram. He, first of India`s great publicists, understood the hollowness and inutility of the method of political agitation which prevailed in the pre-independent society. "The Mother of his vision held trenchant steel in her twice-seventy million hands and not the bowl of the mendicant. It was the gospel of fearless strength and force which he preached under a veil and in images in Anandamath...."

This almost paints a picture that Bankim Chandra was a precursor of the extremists, as opposed to the moderates, in the nationalist movement. Whether this was so, is doubtful. But the important point was that Aurobindo Ghosh correctly pointed to the role the song played: `The bare intellectual idea of the motherland is not in itself a great driving force`, but the vision that inspired people was something more- `a form of beauty that can dominate the mind and seize the heart`. Truly, Vande Mataram in pre-independent society had successfully gathered up fighters for a common cause, owing to its sublime innate and mystic force of vivacity.

Vande Mataram in pre-independent society had to go through umpteen trials and tribulations, with esteemed nationalists at times speaking for it, at times, against it. However, nationalist pamphlets audaciously spoke for the song and the novel, Anandamath. Aurobindo Ghosh helped to popularise the song through the journal he edited, Bandemataram, which was not only the organ of the revolutionary Jugantar Party but also a very popular broadsheet read by many who were not part of the movement. Among the exhibits put up by the Prosecution in Aurobindo Ghosh`s trial, one has numerous citations of Bankim Chandra in the journal. Similarly, the other periodical Ghosh started, Sandhya, upheld to its readers Vande Mataram as the national anthem and the novel Anandamath as the repository of the ideals to be followed. An article exhorted in the periodical, `In every village, every town Anandamath must be established…Then the Mother`s name will be uttered by seven crores of throats and every side will resound (with) Bande Mataram,`.

Vande Mataram in pre-independent society had to go through umpteen trials and tribulations, with esteemed nationalists at times speaking for it, at times, against it. However, nationalist pamphlets audaciously spoke for the song and the novel, Anandamath. Aurobindo Ghosh helped to popularise the song through the journal he edited, Bandemataram, which was not only the organ of the revolutionary Jugantar Party but also a very popular broadsheet read by many who were not part of the movement. Among the exhibits put up by the Prosecution in Aurobindo Ghosh`s trial, one has numerous citations of Bankim Chandra in the journal. Similarly, the other periodical Ghosh started, Sandhya, upheld to its readers Vande Mataram as the national anthem and the novel Anandamath as the repository of the ideals to be followed. An article exhorted in the periodical, `In every village, every town Anandamath must be established…Then the Mother`s name will be uttered by seven crores of throats and every side will resound (with) Bande Mataram,`.

In 1917, J.C. Nixon, an ICS official in the home department compiled a report on revolutionary organisations in Bengal, gleaning information from court cases and records of the intelligence department. Nixon thought that the distinguishing trait of Aurobindo Ghosh was `setting out his political doctrines in religious garb`. Ghosh`s journal Bande mataram was prosecuted for violation in 1907, shortly before he was tried for manufacturing bombs and spreading sedition. It was an evident fact that Vande Mataram was triumphantly acting as a tremendous inciter in various phases of pre-independent society. While Aurobindo Ghosh`s Jugantar Party was active in western Bengal, the revolutionary party in eastern Bengal was the Anushilan Samiti. The intelligence department report compiled on this group by B.C. Allen, the district magistrate of Dhaka in 1907, mentions that their `war cry` was Vande Mataram, and occasionally Bharat-mata ki jai; a `Bande Mataram promise`, a vow taken by entrants to the Samiti, was required of all members. The traditional festival of Rakshabandhan was reinvented for nationalist purposes as a means of asserting national unity. On that day Vande Mataram was a slogan shouted in public by processionists, until in some areas in Bengal the slogan was banned. The pre-independent society perfectly mirrored the both sides of extremism, all for the song, Vande Mataram.

The `official` British attitude to the song Vande Mataram is reflected very clearly in the anonymous article on Bankim Chandra in the Encyclopaedia Britannica in its edition of 1910. The political significance of Bankim Chandra`s song is fore-fronted: `Of all his works ... by far the most important from its astonishing political consequences was the Ananda Math which was published about the time of the agitation arising out of the Ilbert Bill.` The song is described as `the work of a Hindu idealist who personified Bengal under the form of a purified and spiritualized Kali`. Most of the verses, the article states, are `harmless enough` but some parts `are capable of very dangerous meanings in the mouths of unscrupulous agitators`, given the context in the novel. The novel states that the hymn was being sung while rebels attacked British forces. Pre-independent society was not just merely about fighting eternally for the motherland, several other factors needed to be taken into account. Thus, Vande Mataram during those times made an impact on the political scale too.

During Bankim Chandra Chatterjee`s lifetime the Vande Mataram, though its dangerous tendency was recognised, was not used as a party war cry. It was not raised, for instance, during the Ilbert Bill agitation, nor by the students during the trial of Surendra Nath Banerjee in 1883. It had, however, obtained an evil notoriety in the agitations that followed the partition of Bengal, 1905.

During Bankim Chandra Chatterjee`s lifetime the Vande Mataram, though its dangerous tendency was recognised, was not used as a party war cry. It was not raised, for instance, during the Ilbert Bill agitation, nor by the students during the trial of Surendra Nath Banerjee in 1883. It had, however, obtained an evil notoriety in the agitations that followed the partition of Bengal, 1905.

In this view during the pre-independent society, emphasis on the semiotics of Hindu derivation in the novel and the song assumed significance in light of the British Indian bureaucracy`s strategy, vis-Ã -vis the swadeshi agitation. The advantage of having a section of Muslim opinion in their favour was not lost on the British officialdom. The Rowlatt Report of 1917 on seditious movements in India underlined the breach within the ranks of the native subjects revealed by the half-hearted attitude of a section of Muslim opinion to the swadeshi agitators. Vande Mataram had by now, turned into a cause of national significance. As such, quite mirroring those times, parties were divided in opinion and beliefs. During 1905-08, a major objective of intelligence reports was to focus on that breach; instances of efforts to create an alliance between leaders who influenced opinions in the Hindu and Muslim communities were closely watched, evidently with apprehension.

Vande Mataram in pre-independent society was the singular cause of umpteen journals, write-ups, or even newspapers, surprisingly from Britishers also. The appeal of the slogan was not, of course, limited to Bengal. One of the earliest instances of its spread in Maharashtra occurs in the List of Proscribed Publications of the Government of India in 1910: `a photograph containing portraits of Nana Fadnavis and others ... notorious for acts or opinion of a violent and subversive character...arranged on the words Bande Mataram.` The same year, a ban was enforced on the circulation of Bande Mataram, a journal published from Geneva and later Berlin, containing `seditious and revolutionary ideas`. This monthly `supported by Madam Cama`- Bhikaji Rustomji Cama-was edited and supported successively by Hardayal, V.V.S. Aiyar, and Virendra Chattopadhyay. Its importation was prohibited under the Customs Act, but the police reported its circulation in Bengal, Bombay, United Provinces, Punjab and Madras.

Apart from this journal from abroad, many pamphlets containing the slogan were issued in different parts of India despite censorship. Many of these were printed in Bengal, but a vast number elsewhere. Thus, an English pamphlet published in Madras in 1914 addressed people in Punjab to exhort them to rebel against British rule and ended with the slogan Vande Mataram. Such was the aura and authority of the poem or song in the now-legendary pre-independent society. Another English pamphlet, proscribed in 1910 and produced anonymously, was entitled Killing No Murder, and had at its masthead `Jugantar: Jai Bande Mataram`. Another such English pamphlet was issued by the `council of Red Bengal` in 1924. Speeches and writings of `Srijut Arabindo Ghose` in English helped spread the slogan in Maharashtra.

However, the more important channel for popularising the slogan was undoubtedly the so-called vernacular press. Some of these publications were issued by locally organised associations, sometimes ephemeral bodies which put down their name as the publishers of these pamphlets. One gets to know of these pamphlets from the Proscribed Literature List; very few reached the libraries and survived. Among these pamphlets carrying the title Vande Mataram were those issued in Hindi or Urdu by the Tilak Vidyalaya in Muzaffarpur (1921), the Yuvak Hindu University of Benaras (1929) and above all by the well-known Nav Jivan Bharat Sabha (1929). Punjab was the source of many pamphlets entitled `Vande Mataram`. The pre-independent society left no stones unturned to make this very song into a slogan, raching as far as England. This included a series of pamphlets published from Lahore by Ram Prashad (1921), another series under the same title published from Lahore in Hindi (1924) and a pamphlet in Urdu by Lai Singh entitled `Bande Mataram, Sat Sri Akal, and Allah-o-Akbar` (1921). There were also a number of pamphlets entitled `Vande Mataram` published elsewhere, mainly in Hindi-from Benaras (1924), from Ahmedabad by `Desha Sevak` (1924), among others. The visual representation of the idea of Vande Mataram was commonly made in oleographs of an image of Bharat Mata accompanied by the slogan and pictures of national heroes.

Although the bulk of this literature was autonomously generated in regional urban centres (and often by people unrelated with the action programme of militant nationalists), there lies also some evidence that the Bengal `biplabis` or militants made a conscious effort to reach across the language divide to access a wider readership.

This was followed by an announcement that henceforth Hindi would be taught at Anushilan Samiti and other places with the help of Marathi volunteers. However, there is no information as regards the effectiveness of such efforts in Bengal. However, leaders like Aurobindo Ghosh and Bipin Chandra Pal propagated their message while touring different parts of India. For the same purpose, nationalist militants from Bengal secretly visited their contacts outside Bengal. Above all, independent of these initiatives, many nationalists outside Bengal made an effort to learn and translate the song. Vande Mataram in pre-independent society was slowly reaching to a second generation of freedom fighters, trying to educate young minds in the mantra of independence.

This was followed by an announcement that henceforth Hindi would be taught at Anushilan Samiti and other places with the help of Marathi volunteers. However, there is no information as regards the effectiveness of such efforts in Bengal. However, leaders like Aurobindo Ghosh and Bipin Chandra Pal propagated their message while touring different parts of India. For the same purpose, nationalist militants from Bengal secretly visited their contacts outside Bengal. Above all, independent of these initiatives, many nationalists outside Bengal made an effort to learn and translate the song. Vande Mataram in pre-independent society was slowly reaching to a second generation of freedom fighters, trying to educate young minds in the mantra of independence.

The most famous of the nationalist poets who helped propagate Vande Mataram was Subrahmanya Bharathi (1882-1921). It is reported that Bharathi translated the song first in 1905 for a periodical and a second time in 1908 when a collection of his works was published under the title Jatiya-gitam. The novel Anandamatham appeared in Tamil translation in 1908 and in another translation in 1919. The novel was also translated into other south Indian languages: Kannada (1897), Telugu (1907) and Malayalam (1909). Among other Indian languages, not unexpectedly, a Marathi translation came first (1897), followed by Gujarati (1901) and Hindi (1906) translations. Needless to say, these and other translations into various Indian languages made the novel one of the most widely known of Bankim Chandra`s works and hence focussed attention on the message of Vande Mataram. The pre-independent society and Vande Mataram under British domination had become a kind of solace, after chanting of which every Indian perhaps felt a sense of pride and supremacy.

Effects of Vande Mataram in Pre-independent Society

Vande Mataram, the song, or poetry, or whatever one wished to interpret during pre-independent society, assumed momentous effects, by the time India was well into the 20th century. Bankim Chandra Chatterjee, the man behind those magical lines, was in the first place, inhibited to publish the lines at all. However, it did see the light of day. Since then, there had been no turning back. Nationalists assumed it as their war-cry against English oppression, it was sung in the 1896 session of Indian National Congress. Illustrious men from every walk of life began to praise it as the most instigating and eliciting description of motherland, inciting on to a free India. Such were the song`s effects that pre-independent society started issuing pamphlets, later to be banned by British law. However, into the darker side, anti-Bankim Chandra messages also did come into being, owing to mysterious and sad circumstances. People had objected to the poem`s supposed criticism about Muslim league in India, leading to later disputes amongst brotherhoods. To sum up, criticism can safely be left out from Bankim Chandra`s verse creation, as effects of Vande Mataram in pre-independent society made the commoner unite under a common cause.

Vande Mataram, the song, or poetry, or whatever one wished to interpret during pre-independent society, assumed momentous effects, by the time India was well into the 20th century. Bankim Chandra Chatterjee, the man behind those magical lines, was in the first place, inhibited to publish the lines at all. However, it did see the light of day. Since then, there had been no turning back. Nationalists assumed it as their war-cry against English oppression, it was sung in the 1896 session of Indian National Congress. Illustrious men from every walk of life began to praise it as the most instigating and eliciting description of motherland, inciting on to a free India. Such were the song`s effects that pre-independent society started issuing pamphlets, later to be banned by British law. However, into the darker side, anti-Bankim Chandra messages also did come into being, owing to mysterious and sad circumstances. People had objected to the poem`s supposed criticism about Muslim league in India, leading to later disputes amongst brotherhoods. To sum up, criticism can safely be left out from Bankim Chandra`s verse creation, as effects of Vande Mataram in pre-independent society made the commoner unite under a common cause.

The message of the song metamorphosed into a slogan in course of political agitation. Aurobindo Ghosh put it that the idea was actually a mantra. As such, practices of the militant nationalist societies adopted it as a vow and a battle cry and used those two words in processions as a slogan to rally the populace. The effect of Vande Mataram in politics of pre-independent society has often been commented upon in general terms. A number of incidents took place as an immediate effect of Vande Mataram.

This incident, or series of incidents, took place in Rajahmundry in what was then known as the Madras Presidency. The Hindu reported in February 1907 that a Bala Bharati Samiti was organised and in Rajahmundry, `students, all wearing Vande Mataram badges, and carrying aloft beautiful banners glittering with bold letters of Vande Mataram and Allah-o-Akbar` marched around the town and `here and there the procession halted to sing the immortal song of Bankim Chandra Chatterjee`. Again in April 1907, the Hindu correspondent from the neighbouring Krishna district reported that Bipin Chandra Pal`s visit to Masulipatam `occasioned political enthusiasm never seen before. His lectures on the Mathra Murthi...(and) the origin and meaning of Vande Mataram` evoked `a wonderful response`. On 19 April 1907, Pal went to Rajahmundry and according to police records, the `shouting of Vande Mataram` became a common occurrence with `seditious meetings` being held in many villages. A perfect example can be seen here of the effect of Vande Mataram during pre-independent India. A European missionary complained that `a native of Rajahmundry got a few street boys and paid them some rupees under the condition that they shout at every European, Vande Mataram`. Students were at the forefront of such demonstrations and led the slogan shouters.

The British principal of the Rajahmundry Arts College reported extensively on the developments to the director of public instruction, regarding the behaviour of students mounted on bicycles. Students were also in the habit of `wearing within the college certain Vande Mataram medals` or badges. The principal warned the students to desist from such practice and expelled a ringleader who wore the badge. This entire incident happened before Pal arrived on 19 April and began to give speeches of `openly treasonable and seditious character`.

Thereafter, more than half the college students began wearing the badge and the principal tried to compel them to remove the badges on the day of the college examinations. While this was going on, someone in the verandah raised the cry of Vande Mataram which was immediately taken up from all parts of the college and in a body students rushed out. The principal seems to have lost his temper and seized one of the offenders `perhaps somewhat roughly by the arm in order to hasten his departure`. The incident provoked 190 out of 215 students to `secede`, i.e. to go on strike. Such can be termedas the effects of Vande Mataram in pre-independent society.

In course of the next month, Principal Hunter suspended 138 students and the Government of Madras, by and large, endorsed his decision and rusticated a number of students for two years. Logan, the director of public instruction, thought that `things would have quieted down had not the malign influence of the Bengalee (Bengali) agitator Bipin Chandra Pal been brought to bear upon the excitable minds of students`. It was quite an affair by the standards of the placid life of educational institutions during those days. Principal Hunter`s account illustrates how the slogan Vande Mataram had become a symbol of defiance of the authorities and the British in everyday life. The meaning of the slogan in everyday conflict situations is displayed clearly in the principal`s long-standing battle against the slogan. British were quite naturally the most affected in course of Vande Mataram turning into a national cry for freedom. Their efforts to thwart those national moves went completely unheard, with nationalists highly disregarding their warning. The intelligent effects of Vande Mataram during pre-independent society cheerfully showed up in such college incidents.

In course of the next month, Principal Hunter suspended 138 students and the Government of Madras, by and large, endorsed his decision and rusticated a number of students for two years. Logan, the director of public instruction, thought that `things would have quieted down had not the malign influence of the Bengalee (Bengali) agitator Bipin Chandra Pal been brought to bear upon the excitable minds of students`. It was quite an affair by the standards of the placid life of educational institutions during those days. Principal Hunter`s account illustrates how the slogan Vande Mataram had become a symbol of defiance of the authorities and the British in everyday life. The meaning of the slogan in everyday conflict situations is displayed clearly in the principal`s long-standing battle against the slogan. British were quite naturally the most affected in course of Vande Mataram turning into a national cry for freedom. Their efforts to thwart those national moves went completely unheard, with nationalists highly disregarding their warning. The intelligent effects of Vande Mataram during pre-independent society cheerfully showed up in such college incidents.

The strike at Rajahmundry College was part of a series of incidents in which the slogan Vande Mataram was used over and again. The collector of Godavari district reports that in Rajahmundry `a Vande Mataram Protection League was started with the object of enforcing their (students`) right to shout Vande Mataram as they pleased`. In the same town, Europeans were often offended by the slogan shouted at them as they passed by.

Early in June 1907, the European Club in Coconada was attacked by a crowd `with roaring cries of Vande Mataram`. The Hindu reported that this was a reaction to another instance of slogan shouting: one Captain Kemp, a champion boxer, felt annoyed with a schoolboy of sixteen who shouted the slogan after him on the street. Kemp beat the boy senseless, a crowd gathered and later attacked the European Club where Kemp had, in the meanwhile, gone to seek the company of his compatriots. There was a general atmosphere of unrest and only `the posse of troops in the Circars` (the northern district of Madras Presidency) brought back normalcy, said the magistrates of Godavari, Krishna, and Guntur districts. The wave of slogan shouting gradually fizzled out, but it left memories of defiance of white men in public places and a proneness on the part of officials to detect defiance in the cry, Vande Mataram. This precise `defiance` was the core effect of Vande Mataram in pre-independent society, with `whites` being crushed by `blacks`.

An interesting sidelight in this series of incidents is provided by the Indian principal of Coconada College. `Vande Mataram was a sacred expression, and it ought not to be used so as to provoke,` he said. While a section of the middle class possibly shared this opinion, to the crowd it meant a cry of defiance to be used as a provocation. Bengal provides many instances. For example, the students of City College, in the town of Mymensingh in north Bengal (now Bangladesh), would shout `Vande Mataram with great vigour and for a considerable time, particularly when the additional district magistrate passed`. Lower-level government officials, like one Babu Uma Charan Roy Chowdhury in Tripura, complained about similar slogan shouting to provoke them; Babu Uma Charan, a loyal British subject, had three students arrested for `singing obscene and National songs` in front of his residence. Summing up reports of various officials, the home department observed that `by far the most serious consequence with the agitation at present (1907) is the harassment to which the police and loyal government officers are being subject to`.

Vande Mataram, with the passing years, although acquired a different status, when one studies the effect of the song in pre-independent society. Shouting the slogan Vande Mataram was, of course, a routine occurrence at `foreign goods boycott` demonstrations in bazaars, in order to rally support and to pressure the shopkeepers. But the presence of the police and officials usually heightened the enthusiasm of the slogan shouters. The official view was that till this time `the fear inspired by the lal-pagri-wallak...played no small a part in keeping the ignorant masses under control`, but that fear became now, in 1905-07, a thing of the past. (The red turban or lal pagri was part of the Bengal policeman`s uniform.) The agitation had reversed public attitude to the police who were now treated with `marked contempt`. Even the presence of troops was not always effective, at least not in stopping slogan shouters.

While it may be true that in the majority of instances the slogan was raised by students and middle-class youth, there also exist police reports of its use by the working classes. An early example was the strike by mill-workers in the British-owned Fort Gloster Mill near Calcutta in October 1905. This sums up an excellent example of effects of Vande Mataram during the era of pre-independence. The superintendent of police reports that mill-workers were given to shouting Vande Mataram at the European assistants. To put a stop to this, the manager, an Englishman, caught hold of two such offenders, whereupon these events followed. The manager`s action was met with tremendous disapproval and an agreement was arrived at amongst them. It explained that at 7.55 pm, the whole 9000 workmen, who were nearly all-local Bengalis, were to shout Vande Mataram. This was accordingly done and `on the (European) Assistants in the different department attempting to stop the disturbances, they were surrounded and several of them were pushed about`. The next day the head of the district police descended on the factory with armed police and affected some arrests. This led to a total strike in defence of those arrested. According to the superintendent of police of the district, when he tried to reason with the workers they told him that `they were all brothers in the mill`.

In part, the contagion of Vande Mataram spread by the government`s own actions, particularly the publicity occasioned by court trials. The proceedings of the trial of nationalist agitators or militant activists were publicised through the newspapers. The trial of Aurobindo Ghosh on the charge of making bombs elevated him to the status of a hero, along with the defence attorney and future Congress leader Chittaranjan Das. Many of the accused at their trial defiantly shouted Vande Mataram in the court of law. Khudiram Bose, hanged in 1908 for the attempted assassination of a magistrate, typically began his statement with `Vande Mataram`. Such luminous instances make one swelled up with pride about the blood and pain fighters had to go through, shouting just a mere Vande Mataram in pre-independent society. Pradyot Bhattacharya, hanged in 1932 for the assassination of the magistrate in Medinipur, wrote in his last message: `Let India awake by our sacrifice. Bande Mataram.` These facts came to light in trial proceedings. Popular imagination was touched by the fact that martyrs made this slogan their mantra.

Disaffection was defined as `political alienation or discontent...which tends to a disposition not to obey` the government. This trend of interpretation as well as the Indian Penal Code made almost any use of the song Vande Mataram open to the charge of sedition. Moreover, in a precedent-making case in Bengal in 1909 the judge ruled that the fact that a printer or a publisher `did not compose the song is also no mitigation`. In cases where the charge was on the basis of seditious songs other than Vande Mataram, the authors were usually more severely punished than publishers. The most well-known case of this kind was two years of rigorous imprisonment of a Bengali folk poet Mukunda Lai Das in 1909. A supreme and firm paw had been established by crusaders, with a single chant of Vande Mataram in the times of pre-independence.

Besides regular affairs of British versus Indian combats, Vande Mataram also had impacted upon hugely in the scholarly society of art and culture during pre-independent society. Visual representations of the mother country as portrayed in Vande Mataram were very popular. Among them were oleographs, somewhat like the `calendar pictures` sold in bazaars, then and now. There are descriptions of some of these in the police reports, e.g. `photo entitled Aryamata: contains portraits of Shyamji Krishnavarma and other extremists arranged around an allegorical representation`. Or `photograph entitled Vande Mataram: photographs of well-known extremists and nationalists, with a leavening of allegorical pictures .... inserted into the word Vande Mataram`. Or `photograph entitled National Hero: the National Hero holds in his left hand a miniature form of the map of India, Vande Mataram is written on his wristlet`. Around this figure were pictures of Shivaji, Ram Das, Swami Vivekananda, Nana Saheb, Lakshmi Bai, Aurobindo Ghosh and others. The most famous allegorical picture of this kind was in the domain of high art and did not find mention among `proscribed literature`. It was a painting (1906) by Abanindranath Tagore, a founder of the Bengal School of Painting and for a while the principal of the Arts College in Calcutta. This painting of `Bharat Mata` appeared in a Bengali magazine and was later reproduced in many forms, including as a banner in swadeshi demonstrations. Sister Nivedita applauded this painting of `the spirit of the Motherland-the giver of Faith and Learning, of Clothing and Food` (these are symbolised in the painting through objects held in the four hands of Bharat Mata).

Thus, in a variety of media, visual and verbal, Vande Mataram was fore-grounded as the core idea inspiring the nationalist struggle from 1905 onwards. This very reflective statement perhaps sums up the essence or effect of Vande Mataram in pre-independent society, few being able to surpass such a war cry. While the song enjoyed enormous popularity in Bengal-and in translation, elsewhere in India-the slogan as a rallying cry was the more widely disseminated seedling of the nationalist spirit.

Composition of Vande Mataram, Indian National Song

Composition of Vande Mataram implicitly bears Bankim Chandra Chatterjee`s own style of thought in written version. Several theories are put forward for the poem`s composition. The poem was originally composed in a comparatively smaller version, which was later enlarged to include in the novel, Anandamath. Aurobindo Ghosh had very justly translated the poem for the sake of discussion. Bankim Chandra composed Vande Mataram using both Sanskrit and Bengali, overlapping according to his own disposal. This was open to much criticism later, but, however, stood its ground. Bankim Chandra, by using his intellect in the poem, was merely trying to mirror the contemporary times, and to some extent also eliciting autobiographical elements all through.

Composition of Vande Mataram implicitly bears Bankim Chandra Chatterjee`s own style of thought in written version. Several theories are put forward for the poem`s composition. The poem was originally composed in a comparatively smaller version, which was later enlarged to include in the novel, Anandamath. Aurobindo Ghosh had very justly translated the poem for the sake of discussion. Bankim Chandra composed Vande Mataram using both Sanskrit and Bengali, overlapping according to his own disposal. This was open to much criticism later, but, however, stood its ground. Bankim Chandra, by using his intellect in the poem, was merely trying to mirror the contemporary times, and to some extent also eliciting autobiographical elements all through.

Imagery in Vande Mataram

Imagery in Vande Mataram finds excellent usage, considering the age when Bankim Chandra Chatterjee penned it. The poem written in the late 19th century carried a different image, with the 20th century reflecting an entire different imagery in the social context. After the poem was included in novel Anandamath, the outlook in imagery usage changed again. As such, Bankim Chandra can be called a passionate writer, cleverly putting in images and symbolism all through Vande Mataram.

Undoubtedly at that time the religious content of the rhetoric and imagery of the `motherland` in Vande Mataram carried a certain kind of primeval charm. The imagery in Vande Mataram where the representation of the country as mother is being done meant different things to different people and denoted a suppressed feeling or emotion in the then socio political scenario.

Undoubtedly at that time the religious content of the rhetoric and imagery of the `motherland` in Vande Mataram carried a certain kind of primeval charm. The imagery in Vande Mataram where the representation of the country as mother is being done meant different things to different people and denoted a suppressed feeling or emotion in the then socio political scenario.

The political imagery in Vande Mataram also demands special attention. Political scenario was quite different when Bankim Chandra wrote Vande Mataram in the 1870s. At that time no great fuss was made about the lack of congruence between Banga-mata and Bharat-mata. When Bankim Chandra wrote the sapta-koti or seven crore worshippers of the motherland, he evidently had in mind the population of the entire Bengal Presidency which then included Bihar and Chota Nagpur, Orissa, West Bengal, Bangladesh and Assam. The population of this area totalled 6.7 crore approximately in the census estimate (Bankim reported this fact editorially for the benefit of the readers of his literary journal in April 1872). Hence the words sapta-koti, a round figure which rolled out sonorously in the verse and in the usage of imagery in Vande Mataram stands as the total population of the area under the lieutenant governor of Bengal in 1871 and thus that figure included the Muslim population also. Vande Mataram` plaited with its sheer imagery therefore could be interpreted as idolatrous. The imagery of Vande Mataram thus personifies an abstract idea of the nation.

It has been said that the spirit of the novel is encapsulated in the song and imagery of Vande Mataram. The spirit has been identified as dedication to patriotic duty (Haraprasad Sastri), or the idea of the country as the mother (Aurobindo Ghosh), or `the ideology of renunciation on the basis of disinterested action` (Bipin Chandra Pal). There is a remarkable unanimity about the song being the core of the novel. This quite descriptively emote the use of imagery in Vande Mataram, continuously overlapping from novel to poem.

It has been said that the spirit of the novel is encapsulated in the song and imagery of Vande Mataram. The spirit has been identified as dedication to patriotic duty (Haraprasad Sastri), or the idea of the country as the mother (Aurobindo Ghosh), or `the ideology of renunciation on the basis of disinterested action` (Bipin Chandra Pal). There is a remarkable unanimity about the song being the core of the novel. This quite descriptively emote the use of imagery in Vande Mataram, continuously overlapping from novel to poem.

The poem Vande Mataram had been a lyrical ode to the motherland, `giver of bliss, richly watered and richly fruited, clad in blossoming foliage, sweet of laughter, sweet of speech` and strong in having seventy million sons to defend her. The version in the novel written in 1881-82 depicted `Durga holding her ten weapons of war`, the destroyer of foes, as well as the goddess of wealth, Kamala and the goddess of learning, Vani- representations drawn from the imagery of Hindu tradition. This visionary again finds an eloquent expression in the imagery of Vande Mataram.

Although, the tone of imagery in Vande Mataram in the expanded version is different from that of the original poem yet Vande Mataram, Indian national song stand as a logo of redolence and light. Entwined with its imagery the song is still reckoned as the representation of the country.

Impact of Vande Mataram

Impact of Vande Mataram in times prior to independence was exceedingly sublime, if spoken in the least. Every mind was influenced and drawn to the poem someway or the other. Numerous interpretations followed. When the poem was later absorbed in the novel Anandamath, a different kind of impact was seen from the intellectual class.

In this context, one needs to bear in mind two facts in considering the impact of the poem Vande Mataram a hundred years ago. First, one needs to think of a time when the notion of motherland was not as banal as it became with its repetitious use in propagandist words and clichés and images and in print or cinematic or electronic media. Second, to state that the poem had a wide appeal on account of its evocation of the archetypal is not necessarily the same thing as justifying its conversion into a divine object of worship. The question that comes here is that what accounted for the `belief-producing` power of the poem. The answer has to be sought in the historical location of this piece of writing in a culture that nurtured the archetype and imagery which Bankim Chandra deployed. However, Bankim did not perhaps deploy with deliberation and calculation, but as the idiom that came naturally to him, since he shared that culture. This was the strength of Vande Mataram, accounting for its tremendous impact on socio-political culture of pre-independence years. However, the poem`s limitation was also realised in the eyes of its critics, because it was perceived to have excluded those who did not share that culture. But then Bankim Chandra was writing a poem, not the resolution of a political party. It was the political appropriation of it which made the poem a slogan, a contested national anthem and eventually a communally divisive issue.

In this context, one needs to bear in mind two facts in considering the impact of the poem Vande Mataram a hundred years ago. First, one needs to think of a time when the notion of motherland was not as banal as it became with its repetitious use in propagandist words and clichés and images and in print or cinematic or electronic media. Second, to state that the poem had a wide appeal on account of its evocation of the archetypal is not necessarily the same thing as justifying its conversion into a divine object of worship. The question that comes here is that what accounted for the `belief-producing` power of the poem. The answer has to be sought in the historical location of this piece of writing in a culture that nurtured the archetype and imagery which Bankim Chandra deployed. However, Bankim did not perhaps deploy with deliberation and calculation, but as the idiom that came naturally to him, since he shared that culture. This was the strength of Vande Mataram, accounting for its tremendous impact on socio-political culture of pre-independence years. However, the poem`s limitation was also realised in the eyes of its critics, because it was perceived to have excluded those who did not share that culture. But then Bankim Chandra was writing a poem, not the resolution of a political party. It was the political appropriation of it which made the poem a slogan, a contested national anthem and eventually a communally divisive issue.

The archetype of the mother that was worshipped did not need to be anything more than the representation of an idea which was not consciously formulated. And probably nothing but an intuitive swing back to that memory occurs at the moment of the creation of Vande Mataram. No deliberate reasoning on the part of the author, nor calculation of the appeal the archetype evoked. In fact, the difficulty of consciously articulating what is intuitive is encountered by Bankim Chandra Chatterjee when he transplanted the poem he had written into the novel Anandamath; the `explanations` of Vande Mataram are the weakest parts of the novel, didactic and banal.

Some archetypes are representational devices, collectively shared by those who have a shared history, real or imagined. One need not necessarily assume a supra-personal level of consciousness, to enable one to think of such archetypes; these archetypes are commonly observed in historical and cultural phenomena. Bankim Chandra`s contribution was to recall and anachronistically to `nationalise` an archetype which predated nationalism by centuries. This was a significant cause for the impact of Vande Mataram on later nationalism, times much later than Bankim Chandra. Though he had written the poem in the late 19th century, its `real` essence and feel was only comprehended in the whole era of 20th century, which is still going on now. Vande Mataram`s impact on young freedom fighters and crusaders looking towards a more vindictive side of action, took up the slogan as life-blood.

Vande Mataram therefore was not merely an act of rediscovery of something that belonged to the past. It was also a revelation of something that was new, an old object of worship now reinvented as the motherland. The meaning thus attributed is certainly new; the scriptural and mythical origins-the story of the creation of Durga, the gift of various weapons by different gods to her, the particularities of the scriptural narrative all added to the then scenario.

Bankim Chandra had written the poem keeping in mind a very different aspect; he never perhaps had realised such an impact it would make on the society in 20th century, with interpretations still continuing into the 21st century.