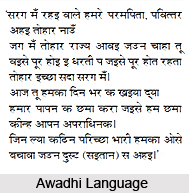

Hindi is that language which absolutely calls for no introduction to the Indian populace. It is perhaps that word which truly redefines Indian ancient customs, its contemporary culture and international relations. Hindi as a language owes its first initiation to India to Sanskrit language and its Apabhramsha (a term used by Sanskrit grammarians after Patanjali to designate dialects of North India that departed from the norm of Sanskrit grammar. The term in Sanskrit literally stands for "corrupt" or "non-grammatical language", and hence Prakrit language absolutely comes under this category). Indeed, Hindi shares various of its alphabetical and linguistics structure to Sanskrit. However, Hindi language as a mass acceptance in Indian society was incredibly witnessed during Islamic invasion, reaching its peak during Mughal Empire. In this context, Hindi also was sufficiently influenced by Urdu, the official language adopted in Mughal and other Muslim royal courts, which later got amalgamated and descended as Hindustani. As such, the language`s essential structure, framing and characteristic phonology received well patronisation from these two languages, i.e., Urdu and Hindustani, besides being shaped by other Indo-European and Indo-Aryan languages. Hindi grammar, in this regard, assumes greatest significance, with grammatical handling being performed meticulously.

Hindi is that language which absolutely calls for no introduction to the Indian populace. It is perhaps that word which truly redefines Indian ancient customs, its contemporary culture and international relations. Hindi as a language owes its first initiation to India to Sanskrit language and its Apabhramsha (a term used by Sanskrit grammarians after Patanjali to designate dialects of North India that departed from the norm of Sanskrit grammar. The term in Sanskrit literally stands for "corrupt" or "non-grammatical language", and hence Prakrit language absolutely comes under this category). Indeed, Hindi shares various of its alphabetical and linguistics structure to Sanskrit. However, Hindi language as a mass acceptance in Indian society was incredibly witnessed during Islamic invasion, reaching its peak during Mughal Empire. In this context, Hindi also was sufficiently influenced by Urdu, the official language adopted in Mughal and other Muslim royal courts, which later got amalgamated and descended as Hindustani. As such, the language`s essential structure, framing and characteristic phonology received well patronisation from these two languages, i.e., Urdu and Hindustani, besides being shaped by other Indo-European and Indo-Aryan languages. Hindi grammar, in this regard, assumes greatest significance, with grammatical handling being performed meticulously.

Hindi is defined as a `subject-object-verb language` (in linguistic typology, Subject Object Verb (SOV) is the kind of languages wherein the subject, object and verb of a sentence appear or normally appear in that order). This rule for Hindi grammar entails that verbs generally come at the end of the sentence, as opposed to before the object (for example in English). Hindi grammar also exhibits `split ergativity` (referring to that language which treats the argument ("subject") of an intransitive verb like the object of a transitive verb, but markedly from the agent ("subject") of a transitive verb) so that, in particular cases, verbs stand in agreement with the object of a sentence compared to the subject. Different from English, Hindi possesses no definite article (the). The numeral one ("ek") in Hindi can also be employed as the indefinite singular article (a/an) if this is essential to be accentuated.

In addition to being an ergative language, Hindi utilises postpositions (so referred to because they are positioned after nouns), whereas English makes use of prepositions. Other essential differences between these two official Indian languages comprise in the areas of - gender, honorifics, interrogatives, utilisation of cases and numerous tenses. While being elaborated and rather complex in essence, Hindi grammar comparatively maintains a regularity, with irregularities being somewhat limited to its complexities. In spite of unlikeness in vocabulary and writing, Hindi grammar is almost identical with Urdu. The conception of punctuation having been absolutely terra incognita before the advent of the Europeans, Hindi punctuation employs western conventions such as commas, exclamation marks and question marks. Full stops are sometimes also utilised to terminate a sentence, although the traditional "full stop" (a vertical line) is also common in usage.

Genders in Hindi grammar

There exists two genders for nouns in Hindi language grammar. Hindi grammar entails that all male human beings and male animals (constituting those animals and plants that are comprehended as "masculine") are masculine. Likewise, every female human being and female animal (including those animals and plants that are comprehended as "feminine") are feminine. Things, non-living objects and abstract nouns are also regarded to be either masculine or feminine according to conventional norms. Even as this is the same as Urdu and analogous to various other Indo-European languages like, French, Italian and Portuguese, it is indeed a subject of dare for those who are habitual only with English language, which although an Indo-European language, has dismissed practically all of its gender inflexion.

Interrogatives in Hindi grammar

Besides the benchmark interrogative terms in Hindi grammar of who (kaun), what (kyaa), why (kyõ), when (kab), where (kahã), how and what type (kaisaa), how many (kitnaa), etc., the Hindi word `kyaa` can also be employed as a generic interrogative term. The word is in fact often positioned at the starting of a sentence to reverse and twist a statement into a Yes/No question (formally acknowledged as a polar question, it is a question whose awaited answer is either "yes" or "no"). This process thus makes it apparent when a question is being asked. Interrogatives can also be constituted plainly by adjusting intonation, just like in some questions utilised in English.

Pronouns in Hindi grammar

Hindi grammar includes pronouns in the first, second and third person for singular gender only. Thus, as opposed to English language, there exists no divergencies between he or she in Hindi language. Stating in more precise terms, the third person of the Hindi pronoun is in fact the same as the demonstrative pronoun (this / that). The verb, after it is paired with a noun, generally signals the variation in the gender. The pronouns have further added cases of accusative and genitive, but no vocative ones. There may also at times exist twofold ways of inflecting the pronoun in the accusative case. In this context, Hindi grammar possesses three levels of honorifics required for the second person of the pronoun (you):

• Aap: Formal and honourable form for you. The term exhibits no difference between the singular and the plural. Aap is employed in all formal circumstances and while conversing with people who are senior in job or age. The plural of the term could be emphasised by saying aap log (you people) or aap sab (s?b/ you all).

• Tum: Informal form of you. The term exhibits no difference between the singular and the plural word usages. Tum is utilised in all informal and intimate circumstances and while conversing with people who are junior in job or age. The plural term could be emphasised by saying tum log ( you people) or tum sab ( you all).

• Tu: Intensely informal form of you, as in thou. The term is rigorously singular in formation, its plural form being employed as /tum/. The term tu can almost be perceived as offensive in India, excluding for very close circles or poetic language necessitating the Almighty.

Imperative terms (requests and commands) in Hindi grammar are compatible in form to the degree of honorific being utilised and the verb inflects to exhibit the degree of deference and civility desired. Due to the reason that imperatives may already comprehend politeness, the word "kripaya", which is interpreted to English as "please", is much less common compared to spoken English; this very stated term is usually only employed in writing or declarations and its use in everyday speech may even reflect scoff to a certain extent.

Word order in Hindi grammar

The benchmark word order in Hindi grammar is, on the whole, Subject Object Verb, but areas where different accent or more composite structure is demanded, this rule is indeed readily set aside (provided that the nouns or pronouns are constantly followed by their postpositions or case markers). More particularly, the standard order in Hindi stands as - 1. Subject 2. Adverbs (in their standard order) 3. Indirect object and any of its adjectives 4. Direct object and any of its adjectives 5. Negation term or interrogative, if there is any, and finally, 6. the verb and any auxiliary verbs. Negation is formed by adding the word nah??, ("no") in the appropriate place in the sentence, or by employing na or mat in specific cases. In this context, it is also noteworthy that the adjectives in Hindi grammar preface the nouns they qualify. The auxiliary verbs always succeed the main verb. Looked at as a generalised manner, Hindi speakers or writers wield sizeable freedom in positioning words to achieve stylistic and other socio-psychological effects, though not as much freedom as in profoundly inflected languages.

Tense and aspect of Hindi verbs

Hindi grammatical verbal formation is centred on aspect with dissimilarities based upon tense, normally demonstrated through use of the verb hon? (to be) as an auxiliary. There hence, exists three aspects: habitual (imperfect), progressive (also referred to as continuous) and perfective. Verbs in each aspect are distinguished for tense in virtually all cases with the proper inflected form of hona. Hindi grammar possesses four simple tenses, comprising: present, past, future (presumptive) and subjunctive (referred to as a `mood` by numerous linguists). Verbs are coupled not only to demonstrate the number and person (pertaining to 1st, 2nd, 3rd person in sentence structure) of their subject, but also its gender. Additionally, Hindi language possesses imperative and conditional moods; the verbs must correspond to the person, number and gender of the subject if and only if the subject is not succeeded by any postposition. If this condition is not met with, the verb must correspond to the number and gender of the object (provided the object does not possess any postposition). If this condition is also not met with, the verb agrees with neither. It is this type of phenomenon that is referred to as `mixed ergativity` (this phenomenon is demonstrated by languages that have a partially ergative behaviour, but employ another syntax or morphology - generally accusative - in specific contexts).

Case in Hindi grammar

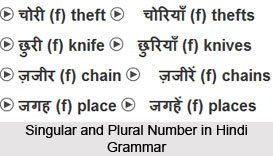

Hindi grammar exhibits that it is a weakly inflected language for case structures. The connection of a noun in a sentence is normally depicted by postpositions (i.e. prepositions that follow the noun). Hindi grammar possesses three cases for nouns. The Direct case is utilised for nouns not succeeded by any postpositions, characteristically for the subject case. The Oblique case is utilised for any nouns that are succeeded by a postposition. Adjectives qualifying nouns in the oblique case will inflect in the same manner. Some nouns further possess a separate Vocative case. Hindi language possesses two numbers: singular and plural - but they may not always be depicted distinctly in every declension.