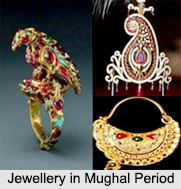

Development of inlaid hardstone jewellery refers to the development of specialized techniques and artistic types in which precious metal is locked mechanically into hardstones (and to some extent other materials, such as ivory). In the ultimate development of this discipline - that which typifies the Mughal period in India - the inlaid precious metal is set with the finest of precious stones, creating a dazzling effect, although one which, in the classic phase of the later 16th and 17th centuries, always remained subject to the taste and artistic control of the practitioners who were rigorously schooled in a rich and long-standing tradition.

Development of inlaid hardstone jewellery refers to the development of specialized techniques and artistic types in which precious metal is locked mechanically into hardstones (and to some extent other materials, such as ivory). In the ultimate development of this discipline - that which typifies the Mughal period in India - the inlaid precious metal is set with the finest of precious stones, creating a dazzling effect, although one which, in the classic phase of the later 16th and 17th centuries, always remained subject to the taste and artistic control of the practitioners who were rigorously schooled in a rich and long-standing tradition.

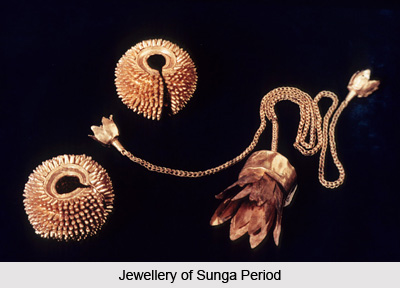

The earliest-known example of precious-metal inlay in hardstones, properly defined, is attributable to the 12th century in the eastern Iranian world. It is most often held by experts that this truly represents the earliest phase of the art. It is also believed to have a connection, at some level, with the rise at just this time and in the same region of a great and influential school of copper-alloy metalwork which is inlaid with silver and copper.

The next examples of hardstone inlay which are known at this point date from the 15th century. These were executed in the same region as the 12th-century work, and comparisons of the methods employed show clearly that the same school of work continued over the intervening period. In keeping with earlier precedent, this 15th century (Timurid period) Iranian school seems predominantly to have taken the form of half-palmette arabesque designs in gold, without any inset stones. The inlay was, however, invariably enlivened by artistically engraved and chiselled interior details of a foliate character. Occasionally, it also included stones, which were set by a method in which metal is scarped inward with a graver and pushed over the edge of the stone, similar to the procedure of modern `bead` settings, most often used for `pave` schemes. This Timurid school of inlay continued under the Safavids in the early 16th century, the tradition also being inherited by the Ottoman Turks, most likely as a result of their capture of the Safavid capital of Tabriz (where they acquired rich booty and numerous craftsmen) in 1514.

Despite several centuries of development in Iran, the difficulties inherent in the inlaying of hardstones (and the like) with massive metal, however pure, limited the freedom of the artist and the range of effective and aesthetically pleasing types of inlay that were possible. These limitations, together with some unfortunate results of attempts to expand the range of types, are most apparent in the extensive Ottoman Turkish material. In this body of work, the problems are particularly obvious in examples set with stones (as distinct from another Ottoman type of inlay in which only flush-inlaid, plain gold is incorporated), where the inlays give the effect of being at odds with the objects they are intended to adorn.

In India, it was once again a case of the ideal technique, Kundan, being available, and it was because of the Kundan technique that the gold of the inlayer, or Zar Nisban was (as the emperor Akbar`s minister and historian Abul-Fazl put it) `made so pure and ductile that the fable of the gold of Parviz which he could mould with his hand becomes credible`. Thus, the inlayer could cut his grooves as he wished and put as much or as little gold whenever and wherever he wanted, and set it with as many or as few stones as required. He was free to make his pieces as much a delight to see and to handle as his taste would allow.