Early Life of Jivya Soma Mashe

Early Life of Jivya Soma Mashe

Jivya Soma Mashe was born in 1923 at Sauna Village in the Warli tribe, just about 200 km at the north of Mumbai. The story of Jivya Soma Mashe is sure to shake anyone of his or her senses. Abandoned by his family from a very early age, he had retreated into complete hushed quieten communicating only by drawing pictures in the dust. This strange attitude soon won him an extraordinary status within his community. His only mode of expression thrived to be drawing. The daily practice of an art until then exclusively ephemeral and practiced at the only Warli ritual occasions drew the attention of the first government emissaries, in charge of the conservation and the promotion of the Warli art.

Career of Jivya Soma Mashe

The smoke of talent never goes unnoticed. Same was the case for Jivya Soma Mashe; he was very soon noticed at national level, unloading directly from the hand of the uppermost political leaders of India like Jawaharlal Nehru or Indira Gandhi, the most important artistic Indian awards, and then on an international level, participating to well-noticed exhibitions, including "Les Magiciens de la terre" in 1989.

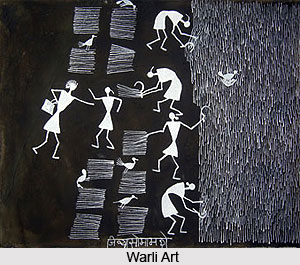

The first government agents sent to preserve and protect Warli art were amazed by his artistic abilities. Jivya Soma Mashe exhibits a finely tuned sensitivity and bizarrely potent imagination, which seem to be the legacy of his early introspective period. Paper and canvas freed him from the constraints of working on rough, sheer walls and he transformed the brusque look of the ephemeral paintings into a free, deeply sensitive style. His sensitivity emerges in every detail of his paintings. Strokes, lines and a mass of dots swarm and vibrate on the canvas, coming together to form clever compositions which reinforce the general impression of vibration. Details and the overall composition both contribute to a sense of life and movement. Recurring themes, from tribal life and Warli legends, are also a pretext for celebrating life and movement.

Jivya Soma Mashe has transformed the appearance of abrupt ephemeral paintings in a free and true style from which emanates his sensibility. This walk is as ubiquitous in Warli landscapes, with its innumerable tracks marking the ground, like the remains of an unfinished settlement, as in the paintings of Jivya Soma Mashe. In his paintings, the walk also fits in the form of tracks, most often represented by a single line. One or several lines that run through and structure the canvas, invite us to follow his always moving characters, his "walkers" whose rough and bold shapes evoke the silhouettes, also basic and decided, of other famous "walkers", represented, or figured, by Alberto Giacometti, Charlie Chaplin or else Jacques Tati.

Jivya Soma Mashe has transformed the appearance of abrupt ephemeral paintings in a free and true style from which emanates his sensibility. This walk is as ubiquitous in Warli landscapes, with its innumerable tracks marking the ground, like the remains of an unfinished settlement, as in the paintings of Jivya Soma Mashe. In his paintings, the walk also fits in the form of tracks, most often represented by a single line. One or several lines that run through and structure the canvas, invite us to follow his always moving characters, his "walkers" whose rough and bold shapes evoke the silhouettes, also basic and decided, of other famous "walkers", represented, or figured, by Alberto Giacometti, Charlie Chaplin or else Jacques Tati.

Looking closely at Jivya Soma Mashe`s paintings, what strikes most is the "movement", the quality of detail, the lightness, and at the same time, the accuracy of the line. The hesitation does not exist in his work. The artist goes to the essential both in the drawing and in the composition, directly, bluntly, with the simplicity of evidence, ingenuity and the natural. Every detail of his paintings is testimony to this. The line and the points abound, in fact swarm on the canvas and fit together in skilful compositions, enhancing the vibration of the whole.

Their extremely rudimentary wall paintings use a very basic graphic vocabulary: a circle, a triangle and a square. The circle and triangle come from their observation of nature; the circle representing the sun and the moon, the triangle derived from mountains and pointed trees. Only the square seems to obey a different logic and seems to be a human invention, indicating a sacred enclosure or a piece of land. So the central motive in each ritual painting is the square, the cauk (or caukat); inside it we find Palaghata, the mother goddess, symbolizing fertility. Significantly, male gods are unusual among the Warli and are frequently related to spirits which have taken human shape. The central motif in these ritual paintings is surrounded by scenes portraying hunting, fishing and farming, festivals and dances, trees and animals. Human and animal bodies are represented by two triangles joined at the tip < the upper triangle depicts the trunk and the lower triangle the pelvis.

Their precarious equilibrium symbolizes the balance of the universe, and of the couple, and has the practical and amusing advantage of animating the bodies. Without this balance, Warli art would be devoid of rhythm and life. The pared down pictorial language is matched by a rudimentary technique.

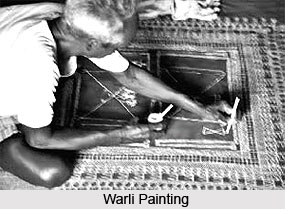

The ritual paintings are usually done inside the huts, which measure about 8 by 6 meters and seldom have partitions. A symbolic separation shares the space between people and cattle. The walls are made of a mixture of branches, earth and cow dung, making a red ochre background for the wall paintings. The Warli use only white for their paintings which is symbolic enough to portray the meanings they want to. Their white pigment is a mixture of rice paste and water with gum as a binding. They use a bamboo stick chewed at the end to make it as supple as a paintbrush. The wall paintings are done only for special occasions such as weddings or harvests. The lack of regular artistic activity explains the very crude style of their paintings, which were the preserve of the womenfolk until the late 1960s. But in the 1970s this ritual art took a radical turn.

Jivya Soma Mashe sums up the deep feeling which animates the Warli people, saying "There are human beings, birds, animals, insects, and so on. Everything moves, day and night. Life is movement." The Warli, adivasi, or the first people, speak to us of ancient times and evoke an ancestral culture. An in-depth study of this culture may give further insight into the cultural and religious foundations of modern India.