Influence of folk music in east India has had a great impact on the music as a whole. Folk music of this land, based on songs, had a variegated growth from the early stage when man attained music tones and found interest in giving out his own feelings spontaneously. The subject matters of folk-songs in the eastern region of India concern simple individual relations of man and woman, man in society, man at work and his participation in festivals and functions.

Influence of folk music in east India has had a great impact on the music as a whole. Folk music of this land, based on songs, had a variegated growth from the early stage when man attained music tones and found interest in giving out his own feelings spontaneously. The subject matters of folk-songs in the eastern region of India concern simple individual relations of man and woman, man in society, man at work and his participation in festivals and functions.

At some instances, it is the sex that inspires a young man to sing to himself. A general approach to life is in a sense a basic object of free, spontaneous composition. Impact of religion on folk is another or the next phase. Psychological inclination to religious music is marked in all traditional human expressions. Normal trends of thought and feelings are influenced by religious ideas. Spontaneity of expression is affected. In the primitive stage objects of nature like birds, flowers, clouds, crops, the moon, the river or stream, etc., were reflected in the mirror of the human mind directly, and these appeared in songs straightway. A large section of Bengali songs related to everyday life, family ties between parents and daughters, relationship of husband and wife, etc. Men in society developed work songs of varied nature among all sections of people. When these spontaneous expressions are pressurized by mixed ideas especially motivated, we call it external influence. Folk-song is never a purposive or motivated form of expression.

During some particular periods in the eastern region when society was predominated by religious ideas, various types of festival and functional songs came to the surface. People were not free from influences of religious personalities. There must have been cross currents of religious thoughts when Prakrit dialects were spoken (up to A.D. 900) in this region.

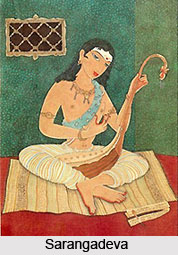

They were also intended for the ordinary people. Such items as were sung were known as Prabandhagiti. The innumerable sections of Prabandha (songs), mentioned in Sangit Ratnakara (1250), included all types of popular music in which names of some groups of folk-songs can also be detected. In the middle ages, every form of religious faith spread through songs and music. For instance:

(1) Mention has been made of Buddhist Mahayana faith represented in Caryagiti of the earliest period;

(2) This faith was formalized in Dharma system and Sunvabad in certain groups of folklore in the early period;

(3) Along with these, folk-songs on Nathas (songs of three Natha Yogis) as familiar in certain rural areas need mention;

(4) Saiva and Sakta music of the eleventh and fourteenth centuries had great appeal for the masses;

(5) Vaisnaba songs of the eleventh and fourteenth centuries prevailed in the whole country;

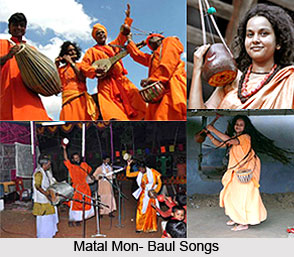

(6) Sakta music of the eighteenth century, Baul songs and Islami music of the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries are all glaring instances of religious impacts on folk musical expressions. Along with these flowed the narratives in local languages, borrowed from the Ramayana, the Mahabharata and the Puranas.

(6) Sakta music of the eighteenth century, Baul songs and Islami music of the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries are all glaring instances of religious impacts on folk musical expressions. Along with these flowed the narratives in local languages, borrowed from the Ramayana, the Mahabharata and the Puranas.

During the later middle ages, the social life of people changed due to the impact of religious and cultural thoughts. Cross-currents of varied religious thoughts and systems greatly affected the psychology of rural folks. In his endeavour to escape from the troubles and tribulations of life, the rural man generally had recourse to sporadic which were recited to himself in home corners or in loneliness. Thus, songs by individuals grew up, that is, forms of individual music had a natural growth in the riverine districts of West Bengal. Certain sections of people were not at all familiar with religious thoughts and problems of society. It was under these mixed circumstances of social life, influenced by various religious thoughts and faiths and complicated by political developments, that compositions of famous East Bengal ballads emerged. Streams of folk-songs of secular type have, thus, been in vogue.

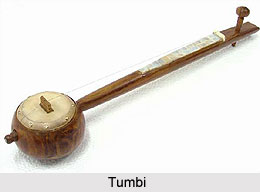

Stages of development of musical peculiarities are not, however, discernible, though many different types of songs are available today in black and white or in oral repository. The musical study of these songs is based on musical features detected during this century after the growing popularity of tunes and rhythms through various processes of mechanical and other devices. Information about the earlier phase scarcely contributes to tracing musicological treatises in which practical forms are preserved. So far as music and organology are concerned, knowledge about them is generally earned through fundamental basic principles which are connected with general traditional principles.

This is proved by the fact that whenever a song, popular or folk, was collected and written, the name of raga occurred in some cases. Even some rural people, connected with the urban society, were conversant with only a few names of times and these tunes were rightly or wrongly cognized as ragas. In fact, raga music influenced the cultured and general people of those days, and it was propagated all over the region through various forms of religious practices. Thus, when local types of music were influenced by religion, people became conversant with at least a few phrases of ragas by constant listening. Actually, these phrases were represented in their tunes but not the ragas in particular. Sometimes these tunes appeared as fragments of ragas. This is only one side of the picture. On the other hand, some adivasis and tribes maintain their own heritage and preserve their own phrases of tunes. The rhythm adds real colour to the character of their music. Some old traits may suitably be squeezed out of preserved forms of tunes blended with folk rendition. But conventional patterns can hardly be attributed to any particular age.