Introduction

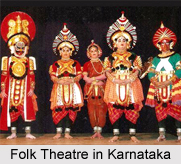

Folk theatre of Karnataka highlights the rich tradition and culture of the state in dancing. This form of theatre is also known as "The Village Theatre", "The People`s Theatre" and "The Rural Theatre". The folk theatre mainly marks on the past of a nation`s theatre and also forms the basic structure of amateur and professional theatre of urban areas. Folk theatre acts as a live spring and recurrently supplies all the essential ingredients to other forms of theatre. It preserves, rejuvenates and also inspires cultural achievements of the people. It forms the supplies and source resources for the progress of theatrical art. "Real India lives in her villages", because the village houses the folk with all its "soft green of the soul" of culture, art and tradition. The folk theatre of Karnataka - music, dance and drama, is mainly preserved and protected by the people of villages. Yakshagana and Sannata are some of the prime examples of folk theatre in Karnataka.

Folk theatre of Karnataka highlights the rich tradition and culture of the state in dancing. This form of theatre is also known as "The Village Theatre", "The People`s Theatre" and "The Rural Theatre". The folk theatre mainly marks on the past of a nation`s theatre and also forms the basic structure of amateur and professional theatre of urban areas. Folk theatre acts as a live spring and recurrently supplies all the essential ingredients to other forms of theatre. It preserves, rejuvenates and also inspires cultural achievements of the people. It forms the supplies and source resources for the progress of theatrical art. "Real India lives in her villages", because the village houses the folk with all its "soft green of the soul" of culture, art and tradition. The folk theatre of Karnataka - music, dance and drama, is mainly preserved and protected by the people of villages. Yakshagana and Sannata are some of the prime examples of folk theatre in Karnataka.

Origin of Folk Theatre of Karnataka

Origin of folk theatre in Karnataka goes back a long way. Folk, the ethnic term suggests a group of kindred people forming a tribe or a nation; now generally used with reference to a primitive stage of social organisation, especially to those emerging from the tribal state.

Origin of folk theatre in Karnataka goes back a long way. Folk, the ethnic term suggests a group of kindred people forming a tribe or a nation; now generally used with reference to a primitive stage of social organisation, especially to those emerging from the tribal state.

Folk Theatre is the theatre of the masses and is also called "The Village Theatre", "The Rural Theatre" and "The Peoples` Theatre". The folk theatre usually reflects on the past of a country`s theatre and forms the basic structure of the professional and amateur theatres of the urban area. It forms the source and supplies resources for the progress of theatrical art. Real India lives in her villages, because the village houses the folk with all its soft green of the soul of culture, art and tradition. It is the village that has protected the folk arts - the dance, music and drama in their original simplicity and sublime glory. Dance, especially. is the most original, spontaneous and universal method of expression of joys of life and that has yet remained the treasure of the village, The mainstay of the folk theatre is its dance, be it ritual, religious or secular.

Spoken Words in Folk Theatre of Karnataka

Dance first and then music seems to have laid the foundations of drama; but the superstructure was built by the spoken word. In its evolution, the theatre has shifted its emphasis from the original fundamentals of dance and music to the spoken word. The real drama and the new drama as we understand to-day, was obviously born at the time when gesture was accompanied by words. The folk theatre of Karnataka has preserved some of the earlier modes of prose drama; earlier modes where the monologue and dialogue formed its basis. If for entertainment and enlightenment of the urban society, there is Puranika, Keertanakara, Pravachanakara, Jangama, Bhagavata Kalajnani and Gamaki who interpret the epics and often impersonate their heroes, there is, for the entertainment of the rural people, Gorava (professional bard), Gondaliga (professional bard singing in praise of Goddess Tulja), Jogi (devotional dancer), Kathegara (story teller), Hasyagara (jester), Nattuva (actor), Nakali (humorist) and Bahurupi (imitator). These performers belong to specified castes, specialised in particular professions which have given them their names. They usually, but inadvertently, speak only the dramatic language while impersonating others. Many types of them like Nattuva, Bahurupi, Nakali and Hasyagara, usually wear specific dresses. Others like Gondaliga, Jogi and Nakali often speak an imaginary dialogue between two persons. Maramma, commonly seen in the Mysore countryside, can be cited as an example who speaks an imaginary conversation which is highly dramatic. The seeds of the drama could be seen again during the Maharnavami festival when boys divide themselves into two groups challenging each other in what is called Ganga-Gouri Samvdda. A step in advance, there is Kole Basava whose performance is built on a planned plot. Often, the animals themselves synchronise their acting with the songs and speech of the trainer.

The Hagaluvesada Ata even now occasionally seen in the Mysore villages brings a group of persons in full make-up and costumes to represent mythological and historical personalities. The group moves from door to door staging dramatic scenes and asking for alms. The Jogi (and Kinnari Jogi) and Gondaliga, both dedicated devotees to Goddesses Yellamma and Tulaja Bhavani, are seen commonly in the villages of North Karnataka, singing songs, telling stories and performing one man shows in front of houses. The accompanist to the Gondaliga acts as the Vidusaka with his many humorous remarks. The Gondaliga performance has also a good dramatic framework, for the artist opens with a prayer (Nandi) in praise of the particular Goddess and then sings in praise of the regional deities. The main story is then enacted in gesture, song and spoken word. At the end, there is the prayer song again, Mangala, to thank the deity for making the performance a success. These relics of the mediaeval modes of the Kannada theatre still linger in the villages, and they are eloquent of the early usage of dance, music and spoken word in making the performance dramatic. The emphasis was gradually shifted from dance to the spoken word. The performance still remained largely ritual, and though gained a hazy framework of the drama, it did not follow any rule of decorum, organic construction nor consistent characterization. Often, it was a curious inter-mixture of crude farcical device and coarse jokes; still the significant point was hit by the employment of the spoken word, which marked the birth of drama in these one man shows.

The origin of folk theatre is to be found in the religious and ceremonial cult through which primitive peoples of all times have sought to promote the welfare of the tribe by incurring the favour of deities and placating the spirit of evil. The rituals played a crucial role in the folk theatre. Rituals, when analysed, show the effort of the primitive man to invoke the aid of the phenomenal powers to get their assistance in keeping the four-fold fears away from his doors, or to offer thanks when his wishes were fulfilled. There is perhaps no ritual which is not either an invocation or a thanksgiving to an unearthly Power. Of the four, the fear of evil (Bhaya) dominated and gave rise to a number of rituals.  The ritual was to please the evil spirit (Devva) which was understood to have been causing the evil, or to please its superior power (Deva) which was capable of controlling it. It was natural that the ghost (who in the eye of the folk, would express themselves by hurling an earthquake or a famine or casting a devouring plague), a master of evils was much feared and respected. The state of Karnataka, with its thunderous skies, pouring rains, thick forests and dangerous valleys, intensely feels the presence of Phenomenal Powers, and so, has been the home of ghost-worship.

The ritual was to please the evil spirit (Devva) which was understood to have been causing the evil, or to please its superior power (Deva) which was capable of controlling it. It was natural that the ghost (who in the eye of the folk, would express themselves by hurling an earthquake or a famine or casting a devouring plague), a master of evils was much feared and respected. The state of Karnataka, with its thunderous skies, pouring rains, thick forests and dangerous valleys, intensely feels the presence of Phenomenal Powers, and so, has been the home of ghost-worship.

Apart from ritual dance, the Folk theatre of Karnataka is also known for dramatic dances. The "dramatic dances" are particularly colourful and impressive because of the costumes and make-up of the participants. The beating-drum is an inevitable accompaniment with fast and changing rhythms. The real ` dramatic ` element is noticed in the dance when the group divides into two camps, one replying to the other either in music or in dance patterns.

Themes of Folk Theatre of Karnataka

Yaksagana, a folk theatrical dance from, deals with themes built around the mythological superhuman personalities, gods, demons and dream lands. Ramayana, Mahabharata and Bhagavata have provided suitable themes in abundance for Yaksagana. Moreover, they maintain a continuity of the Vedic influence by simplifying into didactic stories, the lofty tenets and philosophical teachings of the Vedas and Upanisads. Apart from mythology, the themes are also derived from history.

Themes of Folk theatre of Karnataka mainly consist of mythological and historical elements. Yaksagana deals with themes built around the mythological superhuman personalities, gods, demons and dream lands. Ramayana, Mahabharata and Bhagavata have provided suitable themes in abundance for Yaksagana. Moreover, they maintain a continuity of the Vedic influence, by simplifying into didactic stories, the lofty tenets and philosophical teachings of the Vedas and Upanisads. Instruction with entertainment made a lasting impression on the rural audiences and thus, the lessons of the classics were inculcated. It is in this sense that Yaksagana remained the Night School for the masses, breathing the everlasting spirit of our classical Sanskrit literature.

Themes of Folk theatre of Karnataka mainly consist of mythological and historical elements. Yaksagana deals with themes built around the mythological superhuman personalities, gods, demons and dream lands. Ramayana, Mahabharata and Bhagavata have provided suitable themes in abundance for Yaksagana. Moreover, they maintain a continuity of the Vedic influence, by simplifying into didactic stories, the lofty tenets and philosophical teachings of the Vedas and Upanisads. Instruction with entertainment made a lasting impression on the rural audiences and thus, the lessons of the classics were inculcated. It is in this sense that Yaksagana remained the Night School for the masses, breathing the everlasting spirit of our classical Sanskrit literature.

In selecting the theme for his Yaksagana Prabandha, the composer paid particular attention to the time honoured sentiments of Veera and Raudra. He also provided scope for exploiting war dances. Thus there are elements of Indian mythology on the Yaksagana stage and prominent among them are Krishna- Arjuna Kalaga, Babruvahana Kalaga, Hansadhvaja Kalaga, Karnarjuna Kalaga and others. Even if the Yaksagana Prabandha is about a marriage (Parinaya) or diplomatic dealing (Sandhana), there is perhaps no prasanga without a battle (Kalaga) in it. The title Girija Kalyana suggests a romantic theme, but it opens with the destruction of Daksa- Yajna by Lord Shiva and ends with the battle between the demon Taraka and Subrahamanya, the war God and son of Shiva. Thus with a due emphasis placed on battles, Yaksagana, like Kathakali, is a Tandava Prakara, a variant of the vigorous war-dance of Lord Shiva. Lasya, the delicate dance-pattern, also finds its place but only too occasionally, as in Bheesma Parva, when three princesses softly dance with appropriate gesture to portray their bathing in the river Ganges, or as in Ravana Digvijaya when Ravana with his symbolic dance, washes his feet, hands and face before worshipping the Sivalinga.

But the very life of Yaksagana is valour and power, its dominant sentiments, Veera and Raudra which ideally befit a Tandava Prakara. Only recently, themes are drawn from Indian history and even here, due consideration is given to providing sufficient scope for battle dances.

Rituals of Folk Theatre in Karnataka

Rituals of Folk Theatre in Karnataka have some of the special and interesting stories associated with it. The coastal region of Karnataka, with its thunderous skies, pouring rains, thick forests and dangerous valleys, intensely feels the presence of Phenomenal Powers. Ghost is the presiding deity over destinies of man in many a coastal village and on several fixed occasions in the year, festive ceremonies called Kola, Nema, Agel Tambali Bandi and Ayana are celebrated with great eclat. On all these occasions, the particular ghost Bhuta, when invoked, possesses a dancer who is gorgeously dressed for the occasion and decrees through him the destiny of the individual and community.

Rituals of Folk Theatre in Karnataka have some of the special and interesting stories associated with it. The coastal region of Karnataka, with its thunderous skies, pouring rains, thick forests and dangerous valleys, intensely feels the presence of Phenomenal Powers. Ghost is the presiding deity over destinies of man in many a coastal village and on several fixed occasions in the year, festive ceremonies called Kola, Nema, Agel Tambali Bandi and Ayana are celebrated with great eclat. On all these occasions, the particular ghost Bhuta, when invoked, possesses a dancer who is gorgeously dressed for the occasion and decrees through him the destiny of the individual and community.

Karnataka has a rich legacy of folk dances or dance drama, most of them ritual and many of them dramatic. The dramatic dances are particularly colourful and impressive because of the costumes and make-up of the participants. The beating-drum is an inevitable accompaniment with fast and changing rhythms. The real dramatic element is noticed in the dance when the group divides into two camps, one replying to the other either in music or in dance patterns. They cannot assume the full role of a drama. They do miss a chiselled plot (though some of them like Malekudiyara Kunita and Paravantara Kunita have their own broad themes), rehearsed dialogues and also a non-participating audience. They still fulfil a fundamental purpose of the theatre as a successful media of self expression. They have also contributed patterns in music and dance instruments, costumes and methods of make-up to the folk drama.

Rituals Drama of Folk Theatre in Karnataka

Coastal village has its sacred ghost abode (Bhutasthana), a small building measuring about twelve square yards. The only small door faces either to the East or West. There is a swing cot inside the abode on which is placed a figurine made of brass or bronze in the shape of human being, tiger, boar or bison. A priest (Pujari) worships the figurine every day, but the real pomp and splendour is witnessed only on days of festivals like Kola. It is on that occasion the impersonator called Mani is carefully dressed up in the gorgeous costumes mostly made of indigenous vegetations. He is also painted and decorated in the traditional manner. The colourful costume differs in detail in cases of different ghosts though the general pattern of it is roughly the same. When the impersonator comes into the arena to give faith and assurances, he is taken to be directly under the influence of the particular ghost. The dancing party of men, called Nalke, all made up in the traditional massive costumes, with gaggara tied up to the ankle and swords in hands, dance around the ghost` to the vigorous beating of Tamani the traditional drum. Songs of prayer pad thane (prarthane) are sung in high pitched chorus all in praise of the particular ghost. The atmosphere will gradually grow into a state of intensity with the faster tempo of the drumbeat and the dance of Mani and Nalke. It is then that Mani will come to be possessed to speak under the spell of the spirit. The whole thing is the new creation of an unearthly art, full of grotesque grandeur and tension. The verdict of Mani is respectfully obeyed and the Bhutasthana has yet remained a highly respected and strictly obeyed institution in the coastal village. The point for consideration here is the very basic idea of impersonation and the act of rousing a sentiment; a sentiment of heroism worked out by the ferocious dance of Mani whose whole body is employed as a harmonious means of expression. Though devotional initially, the dance vigorously works up into a climax of valour and it suggests that at one stage or the other, all other folk dances including Yakshagana have taken their basic patterns from the Bhuta dance. Shri Muliya Timmappayya considers in addition, that the make up and costumes of the ghost impersonator has imprinted its influence on Yakshagana.

The head-dress called Battalu Kirita worn by demons and villains (prati-nayaka) in Yakshagana which seem to have evolved from the head-dress of Mani supports this inference. The indigenous colours called Karadala and Ingalika traditionally used for the make-up of Mani of Bhuta sthana are also used by the Yakshagana artist for his make-up, and thirdly, the procession of the Bhuta and the Bhetala surrounded by the singing Nalkes would give a highly similar picture to that of the court scene in Yakshagana. These hints suggest that the oldest available ritual dance of the coastal tract of Karnataka might have provided some of its motifs and characteristics which came to be fundamentals of the later folk entertainments.

Naga Nritya as a Form of Ritual Dance

Naga Nritya or Cobra dance, which is famous in the region of Karnataka, reminds one of the token worship of the olden days. It is often said that while Naga Nritya is performed with essential animation, real reptiles come from somewhere and present themselves to the dancer awaiting his dictates. Nagamandala is the festive occasion when the Naga dance forms a part of the worship. The arena is traditionally decorated with coloured flour rangavalli and is made up for the performance. The dancer paints himself and comes out in the well matching costume to create a perfect make-belief. Naga Nritya, like the Bhuta Sthana, is a ritual dance-drama that is carried down from the past. The emphasis is not on entertainment in either case as the spectator is also the performer invariably. It is very likely that the Naga Nritya also has given to the other folk entertainments including Yakshagana the motif of its dance, motion and also its indigenous musical instruments.