History of Sarod dates back to about 100 years. It has three identifiable ancestors. Two of these were rababas, short-necked fretless lutes with wooden bodies, cat-gut strings, and a skin-covered chamber resonator. The Persian rababa later came to be known as the Indian rababa, dhrupad rababa and seniya rababa. The third ancestor was the surasingara, a native version of the Persian dhrupad rababa.

History of Sarod dates back to about 100 years. It has three identifiable ancestors. Two of these were rababas, short-necked fretless lutes with wooden bodies, cat-gut strings, and a skin-covered chamber resonator. The Persian rababa later came to be known as the Indian rababa, dhrupad rababa and seniya rababa. The third ancestor was the surasingara, a native version of the Persian dhrupad rababa.

The Persian rababa entered India in the eleventh century with the Gazhnavid occupation of the Punjab. It became an important part of music in the early Mughul courts. During the mid-Mughul period, the legendary Miya Tansen at Emperor Akbar`s court contributed substantially to performance on the rababa. The Tansen lineage, through his son Bilas Khan, perpetuated the dhrupad rababa tradition. The dhrupad rababa remained, along with the Rudra Veena, a pervasive presence in the Hindustani mainstream for over two hundred years after Tansen.

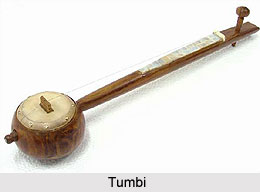

The Afghan rababa was different in design and plan from the Persian rababa. It had entered India from Afghanistan with pathana soldiers in the employ of the early-Mughuls. Soldier-musicians played martial tunes on it, and prized it for the fervor and beat it created. This instrument retained its Afghan music and identity until the mid-eighteenth century, when a line of rababiyas established a link with Hindustani musicians, and diverted its music towards the mainstream.

There is no evidence about when the Afghan rababa was renamed the saroda. The earliest significant sarodiya on record is Ustad Bade Gulam Ali Khan who was the grandson of Ghulam Bandegi Khan Bangash, a rababiya from Afghanistan, and lived in Rewa and Lucknow to finally settle down in Gwalior.

Saroda in Modern India

Despite its considerable status as a mainstream instrument, the Sarod was, until the late nineteenth century, an acoustically unstable instrument with gut strings, and a wooden fingerboard. It adopted the metallic fingerboard and metal strings probably from the surasingara.

After surrendering its most promising features to the sarod, the sumsingara faded into history. Further re-engineering of the Sarod took place during the 1930s to make it the sophisticated and versatile instrument we hear today. Most of this is credited to Ustad Alauddin Khan, and his brother, Ayet Ali Khan, who was also an expert craftsman. After the short-lived surasingara experiment, the rababa or sarod gharanas have not been too enthusiastic about imposing melodic fluidity on the capabilities of the Sarod, or to dilute the percussive element. Within limits, the instrument is being re-engineered to progressively offer a wider choice of idioms in terms of stroke-density relative to svara-density.

Although the world of Sarod recognizes several streams, its idiom is currently represented by three main lineages. The rababa-inspired idiom of Ustad Hafiz Ali Khan, an early twentieth century maestro, was diverted towards a khayal style vocalism by his son, Ustad Amjad Ali Khan. The Mohammed Ameer Khan or Radhika Mohan Maitra stream has reinforced its rababa-oriented idiom in the music of its contemporary exponents, Buddhadev Dasgupta and Kalyan Mukherjea. The rababa and Rudra Veena based style of Ustad Allauddin Khan inspired the genius of his son, Ustad Ali Akbar Khan, to launch the most comprehensive exploitation yet of the distinctive acoustic features of the re-engineered Sarod.