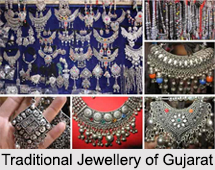

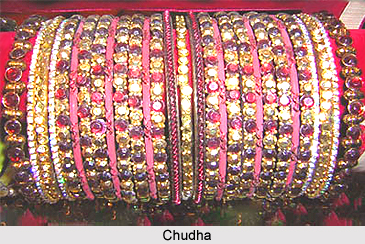

Hammered Jewellery has been popular since the time precious metals were discovered. Apart from their immediate attractiveness of colour and lustre, the most essential characteristic of the noble metals which were discovered and exploited early in the history of civilization is their ability to be hammered. They can also be pressed, stretched and drawn into any form desired and to hold the shape thus given them. This quality which copper also shares with silver and gold is due to the twin properties that these metals posses- malleability and ductility. It is these characteristics which enabled them to reign supreme among non-ferrous metals in use in pre-modern times, and which are still being exploited today to the benefit of mankind.

Hammered Jewellery has been popular since the time precious metals were discovered. Apart from their immediate attractiveness of colour and lustre, the most essential characteristic of the noble metals which were discovered and exploited early in the history of civilization is their ability to be hammered. They can also be pressed, stretched and drawn into any form desired and to hold the shape thus given them. This quality which copper also shares with silver and gold is due to the twin properties that these metals posses- malleability and ductility. It is these characteristics which enabled them to reign supreme among non-ferrous metals in use in pre-modern times, and which are still being exploited today to the benefit of mankind.

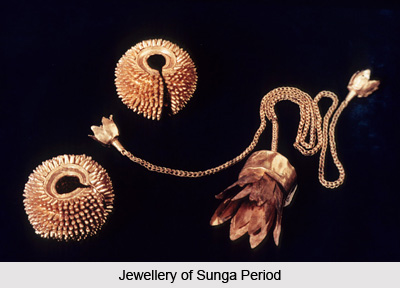

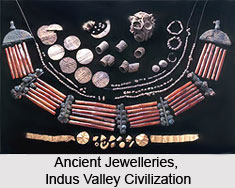

Long before the beginning of written records, artists were taking advantage of these properties to make objects of gold, and in the early historic phases in Mesopotamia, for example, the `raising` of tall, elegant vessels of fully controlled shape from sheet gold by hammering the metal over a variety of stakes was thoroughly mastered. Mesopotamian and other early artists also utilized the inherent responsiveness of these metals to produce relief decoration, which was at times so prominent from the background as to constitute another `raised` element of fully three-dimensional character.

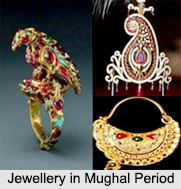

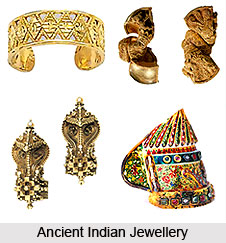

Throughout known history, the artists of India have made full use of the responsiveness of such metals, producing truly impressive objects, from enormous vessels and statues to the most minutely detailed repousse work ever produced, entirely by hammering. Thus, one could say that it was almost inevitable that the period of extraordinary and dynamic artistic growth of the 16th and 17th centuries would give rise to innovations and pinnacles of achievement in decoratively hammered precious metal, as was the case in the other arts. And in hammered work, as in most of those other arts, this age witnessed the introduction of new motifs and approaches from a variety of sources, especially from neighbouring Iran (and through it, in part, ultimately from China) and from Europe.

For various historical reasons, and because of the abundance and high level of patronage in the Subcontinent during this period, India attracted a wide variety of European artists specializing in crafts related to the production of precious-metal and jewelled objects. And in the discipline of hammered precious metals, as in that of enamelling, one can observe the introduction of elements from the repertory of European Renaissance and Baroque design - elements which, in turn, are frequently quite similar to India`s own long-standing traditions. This complex confluence is largely due to the shared heritage of classical ornament, which, although still incompletely traced in the Indian context, was nevertheless widespread and pervasive.

Thus, a number of works of hammered precious works found in India show striking blends of tradition.