Importance of food in the religious practices of Bengal is rather immense. Worshipping the numerous deities of the Hindu pantheon, those from ancient Vedic times as well as those conjured up over time by folk imagination, is part of the daily life of rural Bengal. Although the rituals, prayers and offerings can vary from one deity to the next, some elements are common to all such occasions of worship. They reveal a fertile artistic imagination, springing from the tropical lustiness of the region. And food, as part of such rituals, acquires both literal and metaphorical relevance.

Importance of food in the religious practices of Bengal is rather immense. Worshipping the numerous deities of the Hindu pantheon, those from ancient Vedic times as well as those conjured up over time by folk imagination, is part of the daily life of rural Bengal. Although the rituals, prayers and offerings can vary from one deity to the next, some elements are common to all such occasions of worship. They reveal a fertile artistic imagination, springing from the tropical lustiness of the region. And food, as part of such rituals, acquires both literal and metaphorical relevance.

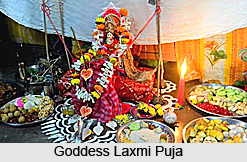

Offerings (cooked and uncooked) made to gods and goddesses express the relevance of food in life. No puja or act of worship is complete without the making of offerings, however simple or meagre. Rice, as expected, is an integral part of such offerings. Unhusked rice and trefoil grasses are presented to the deities along with whole and cut fruits and other foods. The impulse of devotion is complemented with artistry. Even when a woman is worshipping the gods in the solitude of her own home, she will never set out her offerings in a careless fashion. Cut or peeled fruits will be arranged in circular patterns or in blocks of colour and the dhan and durba will be positioned in the middle to provide a navel-like focus. Rice pudding (payesh) is one of the commonest cooked items offered to the gods, combining the two universally accepted items of nourishment.  Once prepared, the pudding is often decorated with dhan and durba before being offered.

Once prepared, the pudding is often decorated with dhan and durba before being offered.

The rituals include the drawing of alpanas, made from rice paste, around her shrine, the symbolic offering of food for her consumption (including the essential rice as well as fruits and sweets) and the reading of a short narrative poem, the panchali, detailing her power and greatness. The symbolic use of rice can also be seen in the practice of filling a wicker basket with dhan (unhusked rice) and placing it alongside the image of the goddess. If, for some reason, the image of the goddess is absent, this basket, called patara, can be a substitute. And in most pictorial depictions, she appears with ears of rice in each hand.

Goddess Lakshmi, the goddess of fortune, is one of the key figures worshipped in Bengal. Her importance, especially for women, is evident in the fact that not only is she worshipped with great pomp and ceremony on the night of the autumn full moon (every god or goddess is honoured on a particular day of the year), but also on every Thursday. Few Hindu homes in Bengal will be without a special niche or alcove in which an image or painting of the goddess is enshrined.  And the weekly worship of Lakshmi demonstrates how blurred the line between art and prayer can be, and how food serves as both an artistic and a ceremonial medium.

And the weekly worship of Lakshmi demonstrates how blurred the line between art and prayer can be, and how food serves as both an artistic and a ceremonial medium.

Worshipping the sun god (referred to as Itu puja or Ritu puja) is perhaps the best example of the ritual use of food grains. A late autumn event, the practice consists of filling an earthen pot with moist earth and five kinds of grains, including rice. A small copper pitcher, filled with water, is embedded in the centre of the pot. On every Sunday, for a whole month, women water the pot to allow the grains to germinate and sprout, and pray to the sun god. By the end of the month, when the harvest is in, they make rice pudding with the newly harvested rice, offer it to the god and, finally, immerse the pot of germinating grains in a pond or river.

Thus, it is evident from the ongoing discussion that food occupies a rather important position in the religious practices of Bengal.