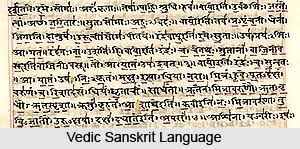

Ancient Indian languages are those which were employed since the time of the Vedas. The language of the oldest Indian literary works, of the songs, prayers and magic formulas of the Vedas, is referred to as Ancient Indian language or Vedic language. This language, though it was based on a spoken dialect, is no longer an actual proper language. It was essentially a literary language transmitted in the circle of priestly singers from generation to generation, and intentionally preserved in its archaic form. The dialect on which this ancient Indian language of the Vedas is based was spoken by the Aryan immigrants in the North-west of India, and was closely related to the Ancient Persian and Avestic. It was not very far removed from the primitive Indo-Iranian language.

Ancient Indian languages are those which were employed since the time of the Vedas. The language of the oldest Indian literary works, of the songs, prayers and magic formulas of the Vedas, is referred to as Ancient Indian language or Vedic language. This language, though it was based on a spoken dialect, is no longer an actual proper language. It was essentially a literary language transmitted in the circle of priestly singers from generation to generation, and intentionally preserved in its archaic form. The dialect on which this ancient Indian language of the Vedas is based was spoken by the Aryan immigrants in the North-west of India, and was closely related to the Ancient Persian and Avestic. It was not very far removed from the primitive Indo-Iranian language.

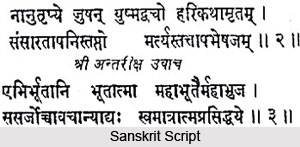

The Vedic language hardly differs at all from the Sanskrit language in its phonetics, except through a much greater antiquity, and especially through a wealth of grammatical forms. Thus for instance, Ancient Indian has a subjunctive which is missing in Sanskrit; it has a dozen different infinitive-endings, of which but one single one remains in Sanskrit. The aorists, very largely represented in the Vedic language, disappear in the Sanskrit more and more. Also the case and personal endings are still much more perfect in the oldest language than in the later Sanskrit. A later phase of Ancient High Indian appears already in the hymns of the tenth book of the Rig Veda and in some parts of the Atharva Veda, and the collections of the Yajur Veda.

On the other hand, the language of the Vedic prose writings, of the Brahmanas, Aranyakas and Upanishads, has preserved only a few relics of Ancient Indian. On the whole the language of these works is already what is called `Sanskrit`. The language of the Sutras belonging to the Vedangas only in quite exceptional cases shows Vedic forms, but is essentially pure Sanskrit. Only the numerous Mantras, taken from the ancient Vedic hymns, i.e. verses, prayers, spells, and magic formulas, which are found quoted in the Vedic prose writings and the Sutras, belong, as regards their language, to Ancient High Indian.

The Sanskrit of this most ancient prose-literature -of the Brahmanas, Aranyakas, Upanishads and of the Sutras- differs little from the Sanskrit which is taught in the celebrated grammar of Panini (probably about fifth century B. C). The best designation is perhaps `Ancient Sanskrit.` It is the language which was spoken in Panini`s time, and probably earlier too, by the educated, principally by the priests and scholars. It is the Sanskrit of which Patanjali says is best learned from the Sisitas, i.e., the learned Brahmins who were well versed in literature.

Sanskrit was certainly not a popular language, but the language spoken in wide circles of educated people, and understood in still wider circles. For, as in the drama dialogues occur between Sanskrit-speaking and Prakrit-speaking persons, so too in real life Sanskrit must have been understood by those who did not speak it themselves Also the bards, who recited the popular epics in the palaces of kings and in the houses of the rich and nobles, must have been understood. That Sanskrit is a `high language` or `class language` or `literary language` has been expressed by the name itself. For Sanskrit- Samskrta, as much as `made ready, ordered, prepared, perfect, pure, sacred`- signifies the noble or sacred language.

Sanskrit was certainly not a popular language, but the language spoken in wide circles of educated people, and understood in still wider circles. For, as in the drama dialogues occur between Sanskrit-speaking and Prakrit-speaking persons, so too in real life Sanskrit must have been understood by those who did not speak it themselves Also the bards, who recited the popular epics in the palaces of kings and in the houses of the rich and nobles, must have been understood. That Sanskrit is a `high language` or `class language` or `literary language` has been expressed by the name itself. For Sanskrit- Samskrta, as much as `made ready, ordered, prepared, perfect, pure, sacred`- signifies the noble or sacred language.

The natural development of Sanskrit was checked through the rules of the grammarians, and it was arrested at a certain stage. For through the Grammar of Panini, in about the fifth century B.C., a fixed standard was created, which remained a criterion for the Sanskrit language for all future times. What is called "Classical Sanskrit " means Panini`s Sanskrit, that is, the Sanskrit which according to the rules of Panini`s Grammar, is alone correct. The great mass of poetic and scientific literature, throughout a thousand years, was produced in this language, the Classical Sanskrit. The reason why Sanskrit as a language evolved no further after Panini was due to the fact that by this time the Aryan language had become divided into two. On the one hand Sanskrit, the language of learning, and in particular the language of the Brahmin caste and of its religion, and on the other hand Prakrit, the language of the masses. These terms did not in fact come into use until some centuries later, but the dichotomy was already established.

Despite its antiquity, Sanskrit is still to be found in use in India today. There are a number of Sanskrit periodicals in India. Also the Mahabharata is still today read aloud publicly, which pre-supposes at least a partial understanding. Scenes from such ornate Sanskrit dramas as Mudraraksasa and Uttararamacharita, are still performed on a primitive stage and greatly appreciated. To this very day poetry is still composed and works are still written in Sanskrit, and it is the language in which Indian scholars even now converse upon scientific questions.