Very often it can be seen that theatre has been used for social progress and for bringing various changes in the society. Theatre for development includes activist and grass-roots bodies, government and non-government organizations (NGOs), as well as socially-aware theatre groups or individuals. The groups working with Dalits, women, children, sex workers, and other marginalized populations, all qualify as practicing theatre for development.

Very often it can be seen that theatre has been used for social progress and for bringing various changes in the society. Theatre for development includes activist and grass-roots bodies, government and non-government organizations (NGOs), as well as socially-aware theatre groups or individuals. The groups working with Dalits, women, children, sex workers, and other marginalized populations, all qualify as practicing theatre for development.

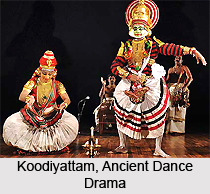

The conscious use of performance for these reasons as an all-India phenomenon can be traced to the Indian People`s Theatre Association (IPTA). This organization sought to raise social and political awareness through theatre and other art forms. Reacting to the fascism and imperialism of the 1940s, the artists and intellectuals of IPTA saw themselves as a socialist vanguard. IPTA productions, involving proscenium and street or open-air performances, never really became grass-roots theatre. However, they were the first to include traditional forms and enlist folk artists, realizing that the `masses` already had performance idioms used for effective communication.

Following IPTA, official agencies were among the earliest to pick up on the advantages of theatre for consciousness-raising and information dissemination. In a country with low literacy and high population, theatre, especially street theatre, provided a low-cost and immediate means of reaching the illiterate. Whereas IPTA included rural performers in its fold, the Indian government encouraged folk artists, often monetarily or through other forms of patronage. This is just to include given social messages in their particular repertoires. The government`s model of development was certainly not about people`s struggle in the revolutionary sense, but focused instead on education, family planning, hygiene, building of pit latrines, and other such national concerns. Other organizations also took up similar themes. The mobilization of theatre for science literacy by the Kerala Sahitya Sangharsh Parishad is a notable example.

In the 1980s and 1990s, NGOs, non-partisan activist societies, and grass-roots groups all over the country increasingly began to use street theatre as a means of social change. Theatre for development now covers subjects as diverse as sexual health, female infanticide, gender, and Dalit concerns. The ideology remains, social progress, but the idea of what constitutes progress gradually evolved. It reflects the historical shift in the notion of development, where earlier agendas of people`s struggle and nation building are now joined by a focus on human and individual rights.

However, theatre practice in the interests of development has not shown much change. The majority continues as crude examples of street theatre, thematically and stylistically; the late Safdar Hashmi`s Jana Natya Manch in Delhi, Praja Natya Mandali in Hyderabad, and Natya Chetana in Orissa are refreshing exceptions to this rule. Much theatre for development also retains the IPTA logic of a leadership speaking to the oppressed, taking up their problems, and providing solutions. The advent of organizations at grass-roots level wrought some change in this dynamic. The person on stage now also belongs to the group whose difficulties are being addressed. However, this person is invariably seen as a social activist, and thus holds to a large extent the exalted position given to the vanguard in the earlier IPTA scenario. Moreover, the activists, grass-roots or not, continue to take on the entire responsibility of choosing, analysing, and solving an issue before presenting it. In this case the audience plays the role of passive consumers.

However, theatre practice in the interests of development has not shown much change. The majority continues as crude examples of street theatre, thematically and stylistically; the late Safdar Hashmi`s Jana Natya Manch in Delhi, Praja Natya Mandali in Hyderabad, and Natya Chetana in Orissa are refreshing exceptions to this rule. Much theatre for development also retains the IPTA logic of a leadership speaking to the oppressed, taking up their problems, and providing solutions. The advent of organizations at grass-roots level wrought some change in this dynamic. The person on stage now also belongs to the group whose difficulties are being addressed. However, this person is invariably seen as a social activist, and thus holds to a large extent the exalted position given to the vanguard in the earlier IPTA scenario. Moreover, the activists, grass-roots or not, continue to take on the entire responsibility of choosing, analysing, and solving an issue before presenting it. In this case the audience plays the role of passive consumers.

Some individuals and organizations reacted to the passive nature of such `theatre or the oppressed`. They opted to experiment with theatre in ways that include and involve the target groups. Boal`s Theatre of the Oppressed, particularly the technique of `forum theatre`, was adopted by workers in different parts of India. In forum theatre, actors present a pressing problem, but instead of providing answers, invite the audience to enact possible solutions. These are then resisted by the actors in socially realistic ways, giving rise to discussion and exploration of the issue through theatre. The goal is two fold such as to look for practicable solutions and more importantly to encourage spectators to act. The term spectators can be explained as to become `spect-actors` i.e. as a step toward becoming active participants in their own struggles.

Jana Sanskriti is based in rural West Bengal. This is specially innovative and successful in its practice of forum theatre, setting up over forty units across the state as well as elsewhere. This usually mobilizes such movements as anti-arrack, anti-dowry, and demand for health care. They pay particular attention to gender, collaborating with women`s NGOs to sensitize audiences while simultaneously empowering women to come forward and seek their own answers through theatre.

An attention to process rather than product is yet another way in which theatre is harnessed for active participation. Organizations working with children welcome theatre as a means of play and expression. Theatre people are also invited to conduct workshops with other groups. There seems to be a small but growing recognition in the development sector that theatre process. The exercises and techniques used by actors and directors can make unique and powerful contributions to individual self-awareness and growth. This is also being useful in building collective trust and collaborative endeavour. While none of these factors create empowerment or development in and of themselves. They are being understood as necessary prerequisites to enable and sustain development. As of now, most of these workshops last only a few days, and the need to see a result or finished product. Those working with women, particularly, accept these benefits. Jana Sanskriti`s female units, Mahila Samakhya in Karnataka, and Voicing Silence in Chennai, an NGO whose credo is `women`s theatre for women`s empowerment`, see theatre process as central to their activities.

An attention to process rather than product is yet another way in which theatre is harnessed for active participation. Organizations working with children welcome theatre as a means of play and expression. Theatre people are also invited to conduct workshops with other groups. There seems to be a small but growing recognition in the development sector that theatre process. The exercises and techniques used by actors and directors can make unique and powerful contributions to individual self-awareness and growth. This is also being useful in building collective trust and collaborative endeavour. While none of these factors create empowerment or development in and of themselves. They are being understood as necessary prerequisites to enable and sustain development. As of now, most of these workshops last only a few days, and the need to see a result or finished product. Those working with women, particularly, accept these benefits. Jana Sanskriti`s female units, Mahila Samakhya in Karnataka, and Voicing Silence in Chennai, an NGO whose credo is `women`s theatre for women`s empowerment`, see theatre process as central to their activities.

Throughout the history of Indian theatre for development, there has been a belief that folk forms are uniquely suited to communicate to the multitudes. In contrast to the governmental approach of providing messages for distribution, the collaboration of Alarippu in Delhi with Pandavani performer Shanti Bai Chelak in Pirda instructively engages the rural artist herself. Chelak incorporates powerful gynocentric performances, reflecting her own sophisticated understanding of gender, in her repertoire. Grass-roots troupes also draw on traditional forms and include village actors. Groups dealing with Dalit problems, such as Chennai Kalai Kuzhu, Chemmani and the feminist theatre of M. Jeeva claim to use Dalit folk expression as a conscious political stance. Furthermore, some traditional performers themselves have taken up issues relating to development. Theatre on the environment by Terukkuttu artist P. Rajagopal of Tamil Nadu Kattaikkuttu Kalai Valarchi Munnetra Sangam offers one such example.