Dhrupad singing just did not vanish into thin air all of a sudden. Numerous serious, sad and grave reasons amalgamated to the decline of this classical musical form. The primary reason can be stated in the form of the gradual destruction of the Mughal Empire into ruins. The Mughals were the principal patrons of dhrupad singing, without whom it looked parentless. Due to this, the cream were no longer interested in its gloomy indifference, refined loftiness, or rigorous dignity. And, they slowly drifted towards khayal, which can be considered the most dismal reason behind dhrupad`s declination. Dhrupad was considered too much of mechanical in its approach. Thus, singers, in order to capture the receding listeners started to learn khayal for survival. The abolition of princely states was also another huge reason for dhrupadi singers` descent. However, it is said that women were always looked down upon, when training in dhrupad music was concerned. Women were considered inappropriate for this genre, due to their style of voice. And khayal was regarded as the best platform for women to showcase their talent, which was also, and is still an indispensable cause for dhrupad`s decline.

The advent of the 18th century, witnessed the decline of dhrupad and the ascent of khayal. The exact historical or cultural reasons for the decline are not clear. It is vital to bear in mind that the Mughal court, which had been the chief nurturer of the form, had run into ruins by the 18th century. It also appears more or less evident that by this time, there was an obvious waning of talent in the field. The best were no longer drawn to it. Its grim impersonality, aristocratic stateliness, austere dignity and, above all, the preponderance of religious and devotional themes, alienated those singers and listeners, who were searching for greater emotional and aesthetic latitude and possibilities. Above all, the mechanical and regimented manner of singing by the less gifted singers of the 17th and 18th centuries also supposedly took away a lot of its brilliancy.

It is an obvious truth that the steady stripping away of emotional and expressive values from any form of art invariably leads to its decline. Soon enough, technique more than aesthetic value, mechanical repetition rather than ingenious innovation, began to predominate among the court singers. Thus devoid of the living heartbeat of ingenuity and feeling, dhrupad declined, for the most part, in the 18th century into a state of inactivity. Even the dedicated and gifted few devoted to the form were obligated to learn and sing khayal for the sake of sustenance. The abolition of princely states following Independence, also hugely to the woes of dhrupad-clans, like the Dagars. They lost their only steady patrons and were compelled to look for other means to compensate themselves and their tradition.

Khayal promised to reimburse for all the gaps of dhrupad. Chief among the new form`s virtues were its emotional agility, ability to accommodate a greater range of moods and themes, and had given way to the greater expressive latitude of khayal, which was also more obliging to secular and romantic themes. Soon enough, the patrons and the singers of the aloof and aristocratic dhrupad wandered to the more inviting and colourful courtyards of khayal. The new form offered the vast space of liberty, through which the creative singer could fly on the newly unfurled wings of his imagination.

Importantly, at least from the first half of the 20th century onwards, it was khayal that offered women singers of North India the space and flexibility for creative expression in classical music. Dhrupad, with its accent on the stately and resonant, is, for the most part, suited to the male voice rather than the female one. While the inherent chauvinism in traditional teaching modes may have sidelined women from learning dhrupad, one feels that the vocal demands placed by it, both formally and aesthetically, cannot be met by the customary female voice. This factor has bracketed out one half of the human world from learning, rendering or propagating dhrupad. Undoubtedly, may women now learn and even perform dhrupad in certain concert circuits. But whether they have been able to equal or even surpass men in dhrupad singing, as they have in the field of khayal, tappa and thumri, is a bold question that remains to be asked, and one that deserves an honest answer even in politically correct times, like these. Whether enlightened equality can reverse the exclusivity of nature or the whimsical snobbery of god remains to be seen.

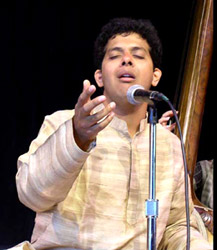

Today, dhrupad, while accepted both nationally and internationally, as one of the oldest and the most unalloyed forms of Indian music, still remains the least listened to and the least applauded of Indian classical musical forms. The demand for dhrupad, for whatever reasons, is more in Europe and North America, than in the land of its birth. In fact, a dhrupad concert is more a rarity than an actuality in the routine concert circuits in the country. With the exception of governmental bodies and organisations, few, if any, private patrons ever sponsor a full-fledged dhrupad concert in the metropolitan cities. Its radiant austerity and its gallant aesthetic standards are possibly what stand in stark contrast to the slick and smooth `management` philosophies of today`s times. Its very `unpopularity` could well be the best commentary that can be made about the cultural situation of the present times.

Governmental bodies have made lean and half-hearted attempts to revive and support this ancient form and its adherents. Yet without a sincere and committed number of students, listeners and connoisseurs, the form cannot evolve and grow. Despondently enough, the best of the younger talent is attracted to khayal, compared to dhrupad for all the reasons mentioned earlier. In other words, the general listening public`s attitude towards dhrupad is, typically, one of quiet disdainfulness and kind indifference, rather than of close involvement and honest appreciation. The future of dhrupad depends on one`s treating it not as a relic worthy of preservation, but as a living musical form, worthy of all one`s deepest attention, love and reverence.