South Indian Bronze Sculpture was highly influenced by Shaivism. South Indian metal sculptures were predominantly made of bronze with a large copper content. The canons of proportion it followed icons followed was similar to those of the Buddhist sculptures.

South Indian Bronze Sculpture was highly influenced by Shaivism. South Indian metal sculptures were predominantly made of bronze with a large copper content. The canons of proportion it followed icons followed was similar to those of the Buddhist sculptures.

Iconography of South Indian Bronze Sculpture

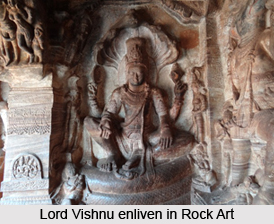

The total height of the statue of South Indian Bronze sculpture that are concentrated in Andhra Pradesh, Telangana, Kerala, Karnataka, Tamil Nadu depended on the hieratic status of the deity represented. Three distinct poses were employed to express the spiritual qualities of special deities. These poses included a directly frontal, static position reserved for gods in a state of complete spiritual equilibrium, poses in which the image was broken more or less violently at two or three points of its axis and a pose reserved for the great gods personifying cosmic movement or function. Mudras were also depicted in South Indian bronze sculptures. There is a fixed pattern of head-dresses and jewellery that were used to drape the icons deities of the Hindu pantheon.

Pallava Art in South Indian Bronze Sculpture

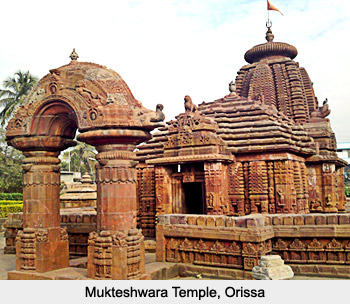

The Pallava rulers constructed bronze sculptures that were inspired by the devotional literature of that period. During the rule of the Chola kingdom, the temple building reached a new height creating a need for idols. Bronze sculptural art in South India touched great heights during that time. The Pallavas laid down the base of the bronze sculptures in South India and the tradition was continued and enriched by the Chola rulers and Nayak rulers.

British Art in South Indian Bronze Sculpture

During the British period, that is during the rule of British East India Company and the British Government in India the patronage was decreased and thus the art form deteriorated but it has somehow survived the colonial rule. Thereafter, the art of making bronze sculpture left the royal courts and took shelter in the countryside. The steady influence of folk art in the physiognomic details of the figures can be seen in the bronze sculptures of South India. The South Indian bronzes are considered to be excellent from the point of view of technique and workmanship.

Modern South Indian Bronze sculptures

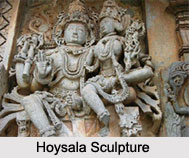

The best instances of South Indian Bronze Sculpture in the 11th century are the images of Shiva saints, now also found in modern markets. One of the most popular of these is Sundaramurtiswami, whom Shiva claimed as his disciple on the youth`s wedding day. This figure is cast in tribhanga pose reminding the onlooker of the sculptures belonging to the Sunga period. A unique combination of traditional elements, subordinated to a kind of elegant attenuation and litheness, is an impressive feature of the South Indian bronze sculptures. It has similarities to some of the pieces of the Gupta period. The figurines of South India appear as marvellous realisations of a moment between movement and tranquility. These statues can be differentiated on the basis of types and attributes.

The most outstanding image of south Indian bronze is that of Nataraja or Shiva, the lord of dance. To the Dravidian imagination, Lord Shiva`s dance, the Nadanta, is the personification of all the forces and powers of the cosmic system in operation, the movement of energy within the universe. The bronze images in the South Indian sculptures present a quality of everlasting nobility. The perfect tenderness of feelings in the figures, the grace and rhythm of the dancing figures, the power, life and action that is manifested, ensure their place among the masterpieces of the world.

Types of Bronze Sculptures of South India

The bronze images of South India are classified into three sections: "Chala" that is moveable, which are in bronze and are easily portable; `utsava beras`, or procession deities; `Achala` (immoveable), in stone, large and heavy.

Classifications of South Indian Bronze Sculptures

According to another classification of the bronze images of South India, there are three kinds namely- Chitra( images are round with limbs completely shown), Chitrarda(figures in half relief) and Chitrabhasa(images painted on walls). The South Indian Bronze images are unique and have different styles of each of the five periods such as the Pallava, early Chola, late Chola, Vijayanagar and modern. The South Indian bronze sculptures follow a canon of absolute beauty, mathematical purity and clarity of form. They were emblematic evocations of a deity that the worshipper had always in his heart and mind.