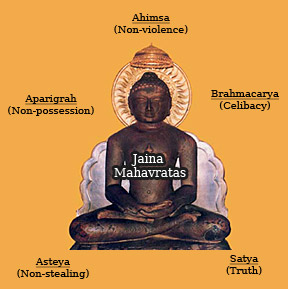

Both the Jains and the Buddhists correctly speculated that a potential for the desired effect must also be present in the cause or causal agent. (For instance, only a mango seed could produce a mango tree because only the mango seed incorporated the potential of developing into a mango tree.) Like the Vaisheshikas, the Jainas perceived atoms as infinitely small. But the Jainas went a step further by positing that the union of atoms required opposite qualities in the combining atoms - as is true in the case of electrovalent bonding.

However, they erred in thinking that covalent bonding (which does not require opposite polarities in the combining atoms) could not occur. But their intuition that opposite polarities created mutual attraction and facilitated chemical reactions was correct. In the Buddhist view, matter was in fact an aggregate of rapidly recurring forces or energy waves. Their theory was illustrated with examples drawn from natural phenomenon involved with light emission. An atom was perceived as a momentary flash of light combining and separating from other atoms according to strict and definite laws of causality. Physical matter was thus seen as a denser and more concentrated form of light.

Development of Philosophical Thought and Scientific Method in Ancient India:

Much of the evidence for how India`s ancient logicians and scientists developed their theories lies buried in polemical texts that are not normally thought of as scientific texts. While some of the treatises on mathematics, logic, grammar, and medicine have survived as such - many philosophical texts enunciating a rational and scientific worldview can only be constructed from extended references found in philosophical texts and commentaries by Buddhist and Jain monks or Hindu scholars (usually Brahmins). These texts attempt to debate the value of the real world versus the spiritual-world. They attempt to counter the theories of the atheists and other skeptics. But in their attempts to prove the primacy of a mystical soul or "Atman" - they often go to great lengths in describing competing rationalist and worldly philosophies rooted in a more realistic and more scientific perception of the world.

The Buddhist worldview was an essentially atheistic worldview. The ancient Jains were agnostics, and within the broad stream of Hinduism - there were several heterodox currents that asserted a predominantly atheistic view. In that sense, these were not religions as we think of today since the modern understanding of religion presumes faith or belief in a super-natural entity.

Hieun Tsang (the Chinese chronicler who traveled extensively in India during the 7th C. AD) who describes the merchants of Benaras as being mostly "unbelievers"! There is other evidence that suggests that amongst the intellectuals of ancient India, atheism and skepticism must have been very powerful currents that required repeated and vigorous attempts at persuasion and change.

One of the most ancient of India`s rationalist traditions is the "Lokayata". Unlike those who believed in reincarnation or an after-life, and in the indestructibility of the human soul - they refused to make artificial distinctions between body and mind. They saw the human mind as part and parcel of the human body - not as some separate entity that could have an independent existence from the human body. They acknowledged nothing but the material human body and the material universe around it. They rejected sacrificial gifts and offerings for the after-life. The Lokayatas dismissed the Vedic priests and their Vedic mantras as nothing but a means of livelihood for those lacking in genuine physical or mental abilities. Instead, they gave primacy to human sense perception, and through the application of the inferential process - they developed their theories of how the world worked. One of the most notable aspects of the Lokayata belief system was their intuitive understanding of dialectics in nature. They were probably amongst the first to understand the nature of different plants and herbs and their utility to human well being. Some later philosophical schools countered the Lokayata arguments concerning mind-body unity by bringing up the evidence of memory. Nyaya-Vaisesika philosophers like Jayanta and Udayana pointed out that the process of daily eating meant that the human body was constantly changing. The process of ageing also pointed to how the human body was ever changing.

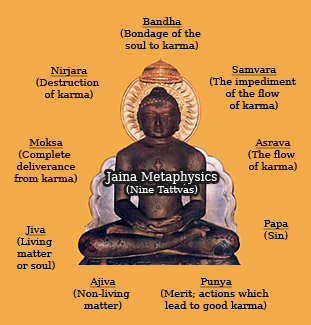

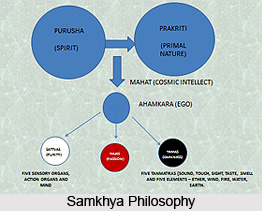

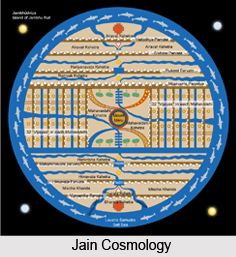

But even amongst those Indian philosophers who accepted the separation of mind and body and argued for the existence of the soul, there was considerable dedication to the scientific method and to developing the principles of deductive and inductive logic. From 1000 B.C to the 4th C A.D (also described as India`s rationalistic period) treatises in astronomy, mathematics, logic, medicine and linguistics were produced. The philosophers of the Sankhya school, the Nyaya-Vaisesika schools and early Jain and Buddhist scholars made substantial contributions to the growth of science and learning. Advances in the applied sciences like metallurgy, textile production and dyeing were also made. Scientific exchanges between Greece and India were mutually beneficial and helped in the development of the sciences in both nations. By the 6th C. A.D, with the help of ancient Greek and Indian texts, and through their own ingenuity, Indian astronomers made significant discoveries about planetary motion. An Indian astronomer - Aryabhata, was to become the first to describe the earth as a sphere that rotated on it`s own axis. He further postulated that it was the earth that rotated around the sun and correctly described how solar and lunar eclipses occurred. The use of the decimal system and the concept of zero was essential in facilitating large astronomical calculation and allowed such 7th C mathematicians as Brahmagupta to estimate the earth`s circumferance at about 23,000 miles - (not too far off from the current calculation). It also enabled Indian astronomers to provide fairly accurate longitudes of important places in India. The science of Ayurveda - (the ancient Indian system of healing) blossomed in this period.

India`s rational age was thus a period of tremendous intellectual ferment and vitality. It was a period of scientific discovery and technological innovation. The rational period thus saw progress on several fronts. Not only did it create an enduring foundation for India`s civilization to develop and mature - it has also had its impact on the growth of other civilizations. In fact, India`s rational period served as a vital link in the long and varied chain of human progress.