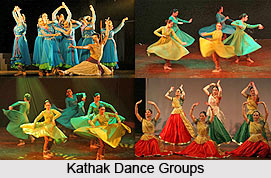

Kathak can be divided into two main parts, namely nritta and abhinaya on the one hand, and tandava and lasya on the other. The nritta portions are presented in a sequence beginning with the traditional entry, known as the amada. Through the amada, the dancer makes his entry into the stage and the invocations to the Hindu god Ganesa were changed into the salami or the court salutation. The amada is usually composed in the medium tempo of a metrical cycle of 16 beats (trital). The amada end with a short pirouette movement and then follows Thata.

Kathak can be divided into two main parts, namely nritta and abhinaya on the one hand, and tandava and lasya on the other. The nritta portions are presented in a sequence beginning with the traditional entry, known as the amada. Through the amada, the dancer makes his entry into the stage and the invocations to the Hindu god Ganesa were changed into the salami or the court salutation. The amada is usually composed in the medium tempo of a metrical cycle of 16 beats (trital). The amada end with a short pirouette movement and then follows Thata.

The Thata is the Kathak dancers way of presenting the different movements of the angas and the upangas. Thata is an initial stance in which the dancer stands with the body firm and upright the right arm bent at elbow and the hand resting on the waist and the left raised a little over. The dancer stands with his feet crossed with the right slightly bent and only the toes touching the ground. There might be some variations in the Thata. The dancer introduces the Kathak with the rhythmic graceful movements of his eyes, eyebrows, neck, chest and shoulders, while the musicians play at a medium tempo in a relaxed mood. It is a sort or warming-up for the full and scintillating dance, which is to follow.

The hands and forearms are held parallel to the chest and the fingertips of one hand touching those of the other. The hands are then moved outwards and forwards with the feet moving backwards and forwards and in a circle. The dancer makes various feet movements virtually standing at the same spot. These entry numbers are soon followed by the presentation of pure dance patterns known as the tora, tukra and Parana. These are successive rhythmic patterns, named so either according to the varying degree of the complexity of the rhythmic pattern or on account of the mnemonics used. Whether they are of the tabla or of the pakhavaj (drum). The tukra is perhaps the simplest variety where the mnemonics are of the tabla and it emphasises one particular type of pattern, which is usually terse and uncomplicated by quarter beats or two-third beats.

The tora is followed by the tukra, which is often presented as the chakkardar tukra. These tukras are built in the same manner as the tirmanams of the varnam in Bharatnatyam. The dancer begins with a rhythmic pattern seemingly slow and in Vilambit laya. And then presenting them finally in a double follows this or a triple laya. The entire sequence is repeated usually three times or in multiples of three.

The Parana is the next variety and it has been identified normally as dance pattern executed to the mnemonics of the pakhavaj. In Parana the tempo is very fast, the patterns highly intricate and rhythmic and the control of the feet so great that at times, when desired, the hundreds of ankle-bells produce the sound of one seven or twelve only. The friendly but challenging competition between the danseuse and the percussionist at this stage is extremely thrilling and fantastically brilliant.

There are sub-divisions and re-classification of the tukras, toras and the paranas. One such re-classification is the composition, which comprises sound of various percussion instruments such as the nagara, pakhavaj, jhang, manjira, duff and tabla. It has a combination of the tandava and the lasya mnemonics. There are tukras, which are known as the sangeet ka tukras. These are compositions usually with mnemonics of one syllable or at best two syllables each, but with some musical quality about them.

The nritta portions of Kathak are presented to a repetitive melodic line known as the nagma. The recurrent line serves the same function as the tonic in a raga. Both the drummer and the dancer weave endless. Kathak knows very few numbers, which aim at or achieve a svara to svara synchronization of dance movement and musical sound. The synchronization is all in the sphere of the metrical cycle. The tarana may be cited as a single exception. Here the dancer does weave patterns to the accompaniment of svaras of the tarana.

The modern performance can include presentation of the three phases of life, creation preservation and destruction. The structure of a conventional Kathak performance tends to follow a progression in tempo from slow to fast, ending with a dramatic climax. A short danced composition is known as a tukra, a longer one as a tora. There are also compositions consisting solely of footwork. Often the performer will engage in rhythmic play with the time-cycle, splitting it into triplets or quintuplets for example, which will be marked out on the footwork, so that it is in counterpoint to the rhythm on the percussion.

All compositions are performed so that the final step and beat of the composition lands on the sam or first beat of the time-cycle. Most compositions also have bols (rhythmic words), which serve both as mnemonics to the composition and whose recitation also forms an integral part of the performance. Some compositions are aurally very interesting when presented this way. The bols can be borrowed from tabla or can be a dance variety.

All compositions are performed so that the final step and beat of the composition lands on the sam or first beat of the time-cycle. Most compositions also have bols (rhythmic words), which serve both as mnemonics to the composition and whose recitation also forms an integral part of the performance. Some compositions are aurally very interesting when presented this way. The bols can be borrowed from tabla or can be a dance variety.

Compositions can be sub-divided:

1. Vandana - the dancer begins with an invocation to the gods.

2. Thaat - the first composition of a traditional performance; the dancer performs short plays with the time-cycle, finishing on sam in a statuesque standing (thaat) pose;

3. Aamad - from the Persian word meaning entry; the first introduction of spoken rhythmic pattern or bol in to the performance;

4. Salaami - related to Ar. salaam - a salutation to the audience in the Muslim style;

5. Gat - from the word for gait, walk showing abstract visually beautiful gaits or scenes from daily life.

6. Kavit - a poem set on a time-cycle; the dancer will perform movements that echo the meaning of the poem.

7. Paran - a composition using bols from the pakhawaj instead of only dance or tabla bols.

8. Parmelu - a composition using bols reminiscent of sounds from nature, such as kukuthere, jhijhikita etc.

9. Tihai - usually a footwork composition consisting of a long set of bols repeated thrice so that the very last bol ends dramatically on sam.

10. Ladi - a footwork composition consisting of variations on a theme, and ending in a tihai.

A typical Lucknow performance of kathak unfolds gradually through several stages, each stage establishing a tempo and dynamic quicker and more intense than the last. The slow introductory invocations to the gods (vandana, pranam) are followed by several sections of abstract pieces (thath, amad, and then in much faster tempo tukra, tora, and paran) that emphasize technique and variety of movement.

In medium tempo come more expressive pieces that rely on the art of suggestion: gat nikas, where the dancer hints at a series of animal or human characters using chals and poses; gat bhav, story telling; thumri, dadra, or ghazal, where the dancer brings to life a song in that style; and tarana, a recent choreographic genre in which both technical and expressive aspects of dance are emphasized.

Technical virtuosity in the form of footwork is usually reserved for the very fastest tempo, and dancers often enter into playful rhythmic competition with their tabla accompanists in the form of a duet (jugalbandi) where one imitates the other, trying constantly to outguess ones opponent. The ultimate aim of the dancer is to develop creative improvisation with the accompanists thereby directing the flow of energy so that it uplifts and involves the spellbound audience before passing back to the performers in the form of warm appreciation.