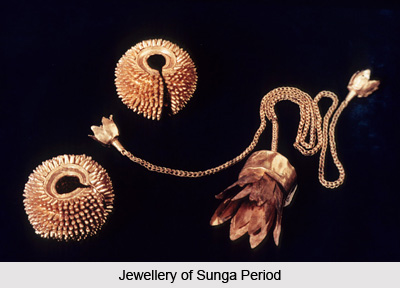

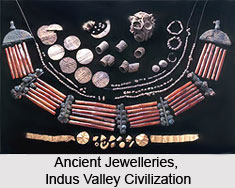

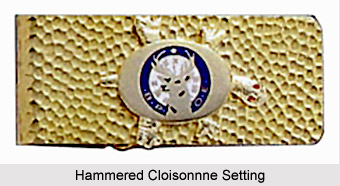

History of stone setting in jewellery and ornamentation goes back a rather long way. In fact, before the beginning of recorded history, mankind was already setting contrasting ornamental stones into artistic objects. All the earliest phases of this practice involved cementing such stones into depressions or cells which had been prepared for the purpose, whether the substrate was of precious metal, a separate stone, wood or some other material. During the first millennium BC, however, a whole series of more secure and elegant, ingenious `mechanical` systems for holding the inset elements was perfected. Leaving aside the simple collet setting, the more advanced of these may be generally characterized as different varieties of highly sophisticated `hammered` settings, which involved the locking of inlays into place by the physical displacement of metal inwards and over their edges.

History of stone setting in jewellery and ornamentation goes back a rather long way. In fact, before the beginning of recorded history, mankind was already setting contrasting ornamental stones into artistic objects. All the earliest phases of this practice involved cementing such stones into depressions or cells which had been prepared for the purpose, whether the substrate was of precious metal, a separate stone, wood or some other material. During the first millennium BC, however, a whole series of more secure and elegant, ingenious `mechanical` systems for holding the inset elements was perfected. Leaving aside the simple collet setting, the more advanced of these may be generally characterized as different varieties of highly sophisticated `hammered` settings, which involved the locking of inlays into place by the physical displacement of metal inwards and over their edges.

It appears that these developments overwhelmingly took place in the Steppelands of Eurasia, whence they spread outwards in cultural streams of varying strength in different directions and at different rates of movement. Among these hammered setting types was the `gipsy` setting, still practised to a limited extent today, in which an isolated stone is placed in an excavated cavity, the surrounding metal then being displaced laterally by blows, typically administered by means of a smooth, round-ended punch.

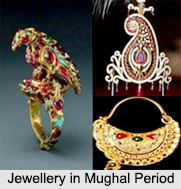

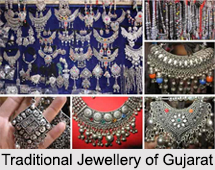

Another Eurasian heritage of the first millennium BC is what we may be called the `hammered-cloisonnne` setting, which, as practised in European objects during the early medieval periods, is reasonably widely known. This type seems to have existed in fully developed form in the Steppes during the first half of the first millennium BC, thence to reach and be practised in India, Iran and Europe in the early centuries of the new era. It was manifest at a particularly high level in Europe, before dying out around the end of the third quarter of the millennium.

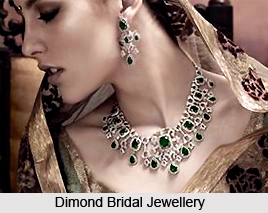

While producing extremely rich effects (particularly as a result of the ability to cover entire surfaces of objects with gemstones), the hammered-cloisonnne setting was extremely labour-intensive because of the need for a high degree of control of design and execution, including the thickness of stones, the height of cloisonnnes and the fit of the two in plan. In Europe it gave way to simpler techniques, especially the collet setting, in which the upper edge of a simple, edge-set, strip-constructed metal ring is forced in and over the perimeter of the stone. Variants of the collet setting were also popular, often in the form of beautifully decorative rosettes provided with claws. These had the advantage of ease in the setting process as well as allowing the display of a larger proportion of the stone, while still holding it securely. Unfortunately, collet settings of whatever kind cannot be grouped closely enough together to give real freedom to the artist in making patterns with stones.

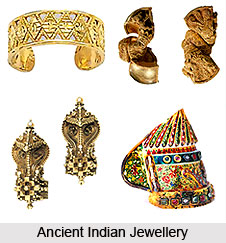

It is surely from the desire to achieve such freedom in design, and against the backdrop of the practice of hammered-cloisonne setting, that the jewellery artists of India, probably in the centuries immediately preceding the birth of Jesus Christ, developed their unique treasure, the Kundan setting. Kundan work is actually a form of gem setting in which gold foil is inserted between the stones and its mount. There is no indication that this technique was ever practised anywhere except in India, despite its obvious advantages, and despite the fact that its visual effect was much imitated in the surrounding regions. Thus in India, the history of stone setting culminates in Kundan jewellery.