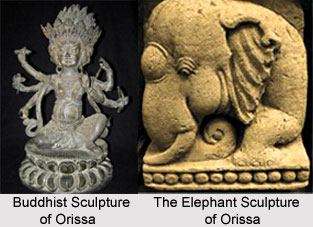

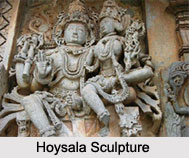

Sculpture of Post-Gupta period-later rock-cut temples were fashioned during the period of Guptas is credited to hold the manifestation of comparatively consistent style. This style reached other parts of the country and stretched to other countries of South and Southeast Asia. In the later period, the art of north Indian kingdoms is found to have influenced by the Gupta style of sculpture in India.

Sculpture of Post-Gupta period-later rock-cut temples were fashioned during the period of Guptas is credited to hold the manifestation of comparatively consistent style. This style reached other parts of the country and stretched to other countries of South and Southeast Asia. In the later period, the art of north Indian kingdoms is found to have influenced by the Gupta style of sculpture in India.

History of Sculpture of Post-Gupta rock-cut temples

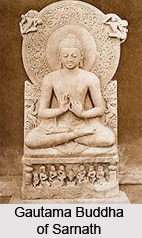

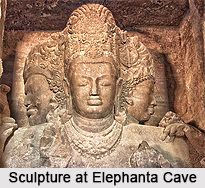

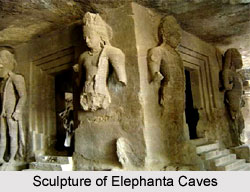

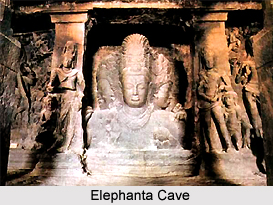

Work is believed to have begun around the present city of Mumbai in the mid 6th century, under the benefaction of the Kalachuris and probably of their precursors, the Traikutakas. The colossal Shiva cave in Elephanta (Gharapuri), an island in Mumbai harbour, possesses an intricate plan, making the most of a vigilantly chosen arrangement of rock and simultaneously deceiving the influence of present-day structural shrines. The Gupta style of sculpture in India did not just form to be the models of the rich art of India for the future but it acted as the ideal for the colonies of India that were situated in the Far East. Sculptures of Guptas are undoubtedly their enduring legacy that has been left for us to see and appreciate. In a nut shell, it can be said that Gupta sculpture style mirrored the moods of the age and was a wonder in itself.

Features of Post-Gupta rock-cut temples

Features of Post-Gupta rock-cut temples

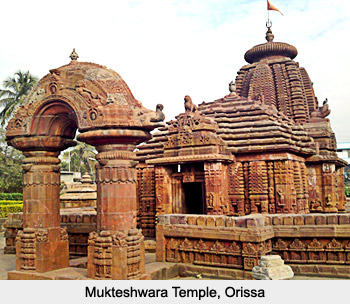

It is basically a rectangular-shaped temple, facing east. The garbhagriha is sarvatobhadrika, each of the four entryways warded by massive dvarapalas and their attendees. On the sides, as an alternative to walls, there are rows of pillars opening up towards antechambers, the northern one leading to another entryway (there is a third one behind the garbhagriha), the southern towards the sculptured rock-face, with, in the centre, the other focal point of the temple, the outstanding Mahadeva image.

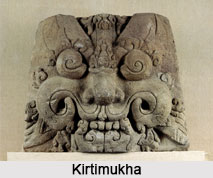

The pillars are comparatively plain, square to mid-height, thereafter round and fluted, including the cushion capitals. The entryways are unornamented; indeed the whole cave is lacking ornamentation, intensifying the effect of massive magnitude and of the great sculptured panels, describing the god in numerous forms and activities, noticeably a Nataraja, an Ardhnarlsvara, a marriage of Lord Shiva and Parvati, and a seated Lakusa.

Devastatingly smashed though they are, the images mix the enrapt and self-involved inwardness which has become the primary dimension of the godhead, with a colossal prevailing dynamism, and in this manner, rather than by the presence of the attendee figures, communicate the indispensable oneness of the human with the divine, which is the keenest theme of Indian art. Greek gods are basically men and women, although romanticised; these statuettes are phenomenal- true immortals, the connection with the human world accomplished by plastic form in a way never possibly rivalled.

The immense Mahadeva image reaches a height of 17ft. 10in. (5.45m.) above the base, itself, approximately 3ft. in height. It is more of a mukhalinga rather than a total figure of Shiva. Its iconographic identification is Sadasiva or Mahesa (the great lord). The right hand of the god is broken; he carries a matulunga (citron) in his left. The face on the proper right, with the serpent, is Aghora-Bhairava, a dreadful or furious manifestation, and that on the left Vamadeva or Uma, Shiva`s shakti, with a lotus. Due to its startling placement in relation to the diverse external entryways, the image gets precisely the amount of light essential to make it look as if it is issuing from a black emptiness, `manifestation from the unmanifested`, an effect intensified by the expression of the central face, sunk deep in consideration and yet immeasurably Olympian.

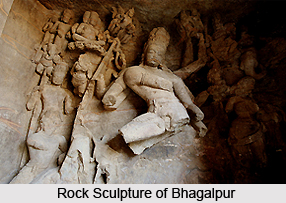

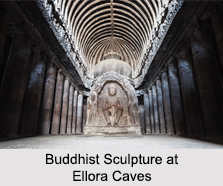

To add to these, sculpture of Bhitaragaon Temple (Madhya Pradesh), the sculpture of Dasavatara Temple (Deogarh), and Vaishnavite Tigawa temple at Jabalpur (Madhya Pradesh) and others are some of the wonderful examples of Gupta sculptures. Rock cut caves have also won laurels to Gupta Empire. The sculpture at Elephanta Caves, the sculpture at Ellora Caves, and Ajanta Caves are worth a visit.

To add to these, sculpture of Bhitaragaon Temple (Madhya Pradesh), the sculpture of Dasavatara Temple (Deogarh), and Vaishnavite Tigawa temple at Jabalpur (Madhya Pradesh) and others are some of the wonderful examples of Gupta sculptures. Rock cut caves have also won laurels to Gupta Empire. The sculpture at Elephanta Caves, the sculpture at Ellora Caves, and Ajanta Caves are worth a visit.

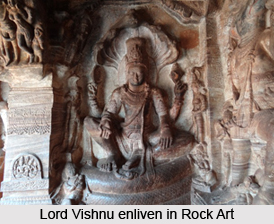

A good amount of these sculptures is found outside, built on prepared rock surfaces. The image of the four- armed Lord Vishnu standing with unadorned cylindrical crowns, footing stiff-legged in samapada, with one of them flanked by ayudhapurusas is one of the most distinguishing images. It personified weapons or symbols.

The Kumara Cave is the earliest of all the incalculable defenders of Hindu shrines, known as pratlharas in north, particularly in south, as being the largest and most astonishing. Thos cave holds the most imposing images.

Typically, the well-built thighs almost unbelievably contrasted with the delicate folds of the tab-ends of the belts and sashes for the Gupta style in early stages. The rock-cut temples of the post-Gupta period enjoy being equally important. Art and architecture of this time incorporated the Buddhist Structural buildings of Gupta Era, the Secular Architecture along with the Brahmanical Architecture.