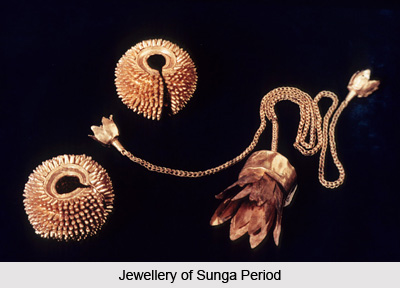

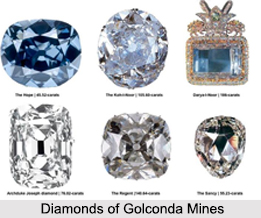

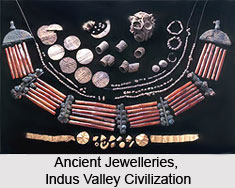

Since ancient times, India has been the home of the world`s most celebrated lapidary industry. Evidence to the same is attested to from as far back as the early Greek and Roman eras. It is almost beyond doubt that, in antiquity and the medieval period, various at present unknown types of relief-carved hardstones had been developed in the region. These include both vessels made of agate, rock crystal etc and precious gems.

Since ancient times, India has been the home of the world`s most celebrated lapidary industry. Evidence to the same is attested to from as far back as the early Greek and Roman eras. It is almost beyond doubt that, in antiquity and the medieval period, various at present unknown types of relief-carved hardstones had been developed in the region. These include both vessels made of agate, rock crystal etc and precious gems.

Fine hardstone relief carving from the early Islamic world, both in rock crystal and in the more abundant wheel-cut glass, is known in very considerable quantities. Such schools would likely have benefited from Egyptian and Sasanian Persian as well as Indian traditions, with cross-fertilizations taking place as a result of the unifying effect of the early Islamic empire. Currently existing examples of this type belonging to the 10 century East Iran show that, in addition to glass and rock-crystal vessels, extremely sophisticated and beautiful relief carving was also practised on gemstone jewellery elements. This tradition probably continued for some centuries beyond the period mentioned, and very possibly fed significantly into the Indian stream, particularly from the 12th century onward.

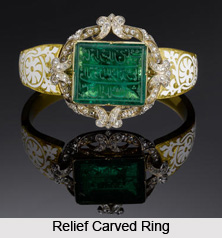

Whatever may be the details of the earlier medieval period`s achievements, there is, from the latter part of the 16th-century onward, a remarkable series of Indian relief-carved emeralds of high levels of design and finish.

On the material side, this was made possible by importing great quantities of large and marvellous emeralds from Colombia, newly available due to the extractions of the Spanish.These stones must have been carved in considerable numbers. However, the intrinsic value of emerald is always a threat to the survival of historic stones because of the great commercial temptation to re-cut those of fine quality. The earliest firmly attributable piece which is known is the grand 233.5carat, flat hexagonal stone with an asymmetrical design of swaying trees which has parallels in the architectural decoration at the emperor Akbar`s capital, Fatehpur Sikri.

On the material side, this was made possible by importing great quantities of large and marvellous emeralds from Colombia, newly available due to the extractions of the Spanish.These stones must have been carved in considerable numbers. However, the intrinsic value of emerald is always a threat to the survival of historic stones because of the great commercial temptation to re-cut those of fine quality. The earliest firmly attributable piece which is known is the grand 233.5carat, flat hexagonal stone with an asymmetrical design of swaying trees which has parallels in the architectural decoration at the emperor Akbar`s capital, Fatehpur Sikri.

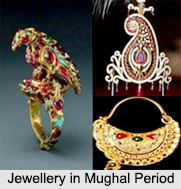

Most of the other relief-carved emeralds of the Mughals are more typical of the object-decorating arts of the period. They feature symmetrical designs which are nevertheless of subtle and lively execution, and are often expressive of the nature of the plant world which usually serves as the inspiration for the carvings. These pieces also typically display to a marked degree precisely the formal beauty which guides their composition, and as such embody established canons of beauty found in most Islamic art.

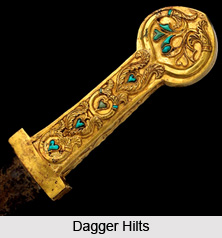

The carved hardstone vessels, dagger hilts and other objects of the Mughals period share much with the series of emeralds in the character of their relief carving. They have an added interest in the manner in which the relief-carved elements relate to their overall form as functional objects, reinforcing the form artistically, and often structurally as well.

A layered agate cameo portrait of Shah Jahan, constitutes a special and particular case. Such controlled exploitation of thinly layered agates for decorative effect has an extremely ancient history in Western Asia and the Subcontinent, but the phenomenon in this painting obviously derives ultimately from classical portrait cameos. The artist clearly relied most importantly and directly on European Renaissance and Baroque examples (the latter representing a revival of the classical tradition), notwithstanding the fact that there was an awareness of ancient cameos in the immediately pre-Mughal Iranian and Indian contexts. Although it has been repeatedly asserted that this piece as well as a comparable piece in the Victoria and Albert Museum, London, was carved by one of the European masters who found patronage in India, others take the position that the painting must have been carved by an Indian trained in the European tradition, since the drawing and rendering are entirely characteristic of the style of Indian artists, as abundantly evidenced in Mughal miniature

paintings.