Introduction

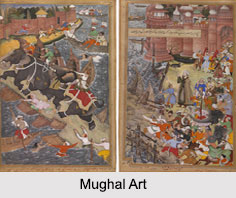

Developed between the 16th to 18th centuries, the Mughal art and architecture is an amalgamation of the Islamic, Persian, Turkish and Indian styles. The Mughal Dynasty was established in 1526 after the victory of Babur in the Battle of Panipat. Their rule marked the extensive displays of art forms, architectural styles that developed vigorously around that time.

Developed between the 16th to 18th centuries, the Mughal art and architecture is an amalgamation of the Islamic, Persian, Turkish and Indian styles. The Mughal Dynasty was established in 1526 after the victory of Babur in the Battle of Panipat. Their rule marked the extensive displays of art forms, architectural styles that developed vigorously around that time.

Development of Mughal Art in India

Mughal Art had first cast its spell in areas like Hyderabad, Deccan, in the centre of India. The monumental splendours of Delhi and Agra are worth noticing and they are a part of the Mughal Art. The ways were old-fashioned with enchanting pillared halls and with shady courtyards and fountains. It has been said that the Mughal Art was very elegant and the artists of this era were very skilful.

Mughal Art had first cast its spell in areas like Hyderabad, Deccan, in the centre of India. The monumental splendours of Delhi and Agra are worth noticing and they are a part of the Mughal Art. The ways were old-fashioned with enchanting pillared halls and with shady courtyards and fountains. It has been said that the Mughal Art was very elegant and the artists of this era were very skilful.

Bidri is an important form of Mughal Art which had a pure and unadorned form. During the Mughal period the tradition of the most robust sort continued even during the Mughal period. It can be said that during the Mughal period as the floral ornament of the Muslim courts took hold, the native Indian taste for sculptural form enriched it, giving Mughal poppies and irises the rhythm and weight of goddesses.

The word "Mughal" describe objects made in India during the rule of the Muslim Mughal emperors - mainly the sixteenth to the eighteenth centuries - not to imply that they were necessarily destined for use at court. Many were made for the Hindu Rajput princes of Rajasthan or the Shia Sultans of the Deccan - the former Mughal vassals.

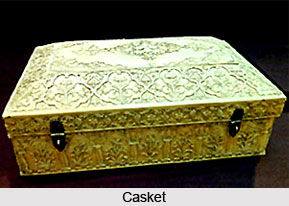

The basic characteristics of Mughal art and architecture are floral motifs rendered with a profoundly Indian sense of weight and volume. Bidri, the black alloy containing mainly zinc, from Bidar in the Deccan, inlaid with copper, brass and silver, has the sombre, fabulous air present also in early Deccani School of painting. It may have been developed to rival the opulent inlaid metal wares of the medieval Middle East. The gold enamels of the Mughal Period are finer. Their shapes are more elegant and graceful and their colours infinitely more delicate and varied.

The basic characteristics of Mughal art and architecture are floral motifs rendered with a profoundly Indian sense of weight and volume. Bidri, the black alloy containing mainly zinc, from Bidar in the Deccan, inlaid with copper, brass and silver, has the sombre, fabulous air present also in early Deccani School of painting. It may have been developed to rival the opulent inlaid metal wares of the medieval Middle East. The gold enamels of the Mughal Period are finer. Their shapes are more elegant and graceful and their colours infinitely more delicate and varied.

The two fold style that was prevalent in India before Mughal Art flourished were the local style connected with the production of Hindu and Buddhist sculpture; the other employed a deliberately Islamic idiom. This style was present in the country during the 16th and 17th centuries. Mughal Art in India to large extent has been influenced by the Persian style and the style of Sindh.

About Mughal Art it can be said that the Sultanate age produced architecture of the highest order. Some of the few characteristics of the Mughal Art were Sultanate metalwork never imitates Middle Eastern styles. These are also a strong emphasis on horizontal lines, in the tradition of medieval Hindu temples in India and the massive, ground-hugging architecture.

The casket of the Mughal period has the pronounced sloping walls and very low dome of Sultanate architecture; moreover, the outline of the two war elephants on its face conform to the traditional Indian configuration of this animal rather than to the Persian. The shape of the flask is of a type which so far remains unknown in the repertoire of Middle Eastern metalwork.

The Hindu sculptural tradition survived at the courts of Muslim Sultans chiefly in the form of splendid metal vessels, mainly incense burners and aquamarines, in the shapes of birds and lions.

Mughal Art and Architecture under the Mughal Emperors

Under the patronage of the first 6 great Mughal Emperors, the Mughal art and architecture flourished and to this day their influence can be witnessed. Discussed below are the artistic contributions of some of the Mughal rulers:

Under the patronage of the first 6 great Mughal Emperors, the Mughal art and architecture flourished and to this day their influence can be witnessed. Discussed below are the artistic contributions of some of the Mughal rulers:

Mughal Art and Architecture during Babur"s Era: The type of structures that evolved during Babur`s regime was not at all provincial or any kind of regional manifestation. Babur constructed several mosques around India, mostly taken from the desecrated Hindu temples. He constructed a series of buildings which mixed the pre existing Hindu particulars with the influence of traditional Muslim designs which was practiced in Turks and Persian culture. Mosques during Babur"s reign was only two, first was the Panipat Mosque, which is currently in the Karnal district of Haryana and the other one is the Babri Mosque in Faridabad district on the banks of the Ghaghara River.

Mughal Art and Architecture during Humayun"s Era: Humayun"s troubled reign did not allow him enough opportunity to use his artistic temperament to the fullest. Humayun constructed some mosques at Agra and Hissar and the palace of "Din-i-Panah" in Delhi which was probably destroyed by Sher Shah. Humayun also had a keen interest in art and the Mughal School of painting began in 1549 when Humayun invited two Persian painters to his court, who directed the illustration of Amir Hamza, a fantastic narrative of which some 1,400 large paintings were executed on cloth.

Mughal Art and Architecture during Akbar"s Era: Out of all the other Mughal Emperors, Mughal art and architecture reached its pinnacle of glory under the reign of Akbar. Few of the greatest examples of Mughal architecture during Akbar"s rule are the Tomb of Humayun, the city of Fatehpur Sikri, the Agra Fort, etc. Under Akbar, Persian artists directed an academy of local painters. The drawings, costumes, and ornamentation of illuminated manuscripts by the end of the 16th century illustrate the influence of Indian tastes and manners in the bright colouring and detailed landscape backgrounds.

Mughal Art and Architecture during Jahangir"s Era: In comparison to the continual architectural activity maintained during the greater part of Akbar`s regime, his son Jahangir, had a fine artistic sense and was fonder of art than architecture. Jahangir was largely influenced by the European style of painting and implemented the technique of single point perspective in his own works of art. Jahangir is notable for his patronage of botanical paintings and drawings. He encouraged portraiture and scientific studies of birds, flowers, and animals, which were collected in albums.

Other than art, Jahangir raised two important buildings during his time, one was the completion of the Tomb of Akbar at Sikandra and the other was the Tomb of Itmad-ul-Daula built by Nur Jahan over the grave of her father.

Other than art, Jahangir raised two important buildings during his time, one was the completion of the Tomb of Akbar at Sikandra and the other was the Tomb of Itmad-ul-Daula built by Nur Jahan over the grave of her father.

Mughal Art and Architecture during Shah Jahan"s Era: During the reign of Shah Jahan, it was known to be the "Golden Age of Mughal Architecture". Like his father Jahangir, Shah Jahan also had a keen interest in the natural world and a taste for paintings, jewel-encrusted objects, textiles, and works of art in other forms. His most important and impressive buildings are the Taj Mahal, Red Fort and Jama Masjid.

Other than architecture, one of the most important work of art produced during Shah Jahan"s reign was the "Padshanama." This work was made to look lavish with generous volumes of gold plating. The "Padshanama," which narrated the achievements of the King, contained several paintings of the courtiers and servants as well.

Mughal Art and Architecture during Aurangzeb"s Era: With Aurangzeb"s accession to the throne, it marked the end of the glorious Mughal art and architecture. His puritanical beliefs provided little encouragement to the development of art. He is usually discredited with the destruction of two most important Hindu temples at Varanasi and Mathura and raising mosques upon them. During his reign the Mughal academy was dispersed and many artists joined the Rajput courts, where their influence on Hindu painting is clearly evident.

Features of Mughal Art and Architecture

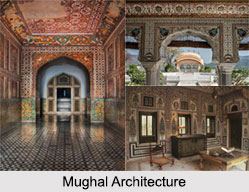

The Mughal rulers built magnificent gates, forts, mausoleums, mosques, palaces, public buildings and tombs etc. One of the similar features of the Mughal architecture was the pronounce domes, the slender turrets at the corners, palace halls supported on pillars and the broad gateways. During the Mughal period, use of red sandstone and white marble was quite common in the construction of the buildings. In the later Indian architectural styles, Mughal architecture has been a great influence, including on the Indo- Saracenic style, Rajput and Sikh styles.

A fundamental feature of the Mughal art was manuscript illumination. A noteworthy example is Persian miniature painting. One of such painting shows a miniature figure of Emperor Akbar, holding a flower and carrying a sword by his side. The flower is symbolic of the calm and peace loving attributes of the Emperor, while the sword is suggestive of Akbar"s royalty and inherent bravery. These Mughal paintings were usually invested with rich imagery and profound meanings. During Humayun`s rule, the intricate illustration of Amir Hamza, a fabulous narrative produced 1400 paintings on cloth that were conducted by expert Persian painters.

Animal Motifs in Mughal Art

Animal Motifs in Mughal Art in India can best be considered in the context of comparable objects made centuries earlier in the Middle East, many of which had similar functions and were made in similar styles. The precise geographical origins and dates of manufacture of the former are still largely conjectural, whereas their Islamic cousins often bear informative inscriptions. Both Indian and Islamic pieces were generally made to be used as ewers (often termed aquamaniles), incense burners or, less frequently, decorative finials for oil lamps (this last function is particularly characteristic of India). Vessels in the shape of animals are significant in the arts of both regions. In the case of India, they represent a rare tradition of non-religious figurative sculpture from a period when realistically rendered figures of any kind were generally avoided in deference to Muslim religious scruples; few of these pieces have survived. In the case of the Middle East, they form virtually the only sculptural tradition that was tolerated during the Islamic period.

Animal Motifs in Mughal Art in India can best be considered in the context of comparable objects made centuries earlier in the Middle East, many of which had similar functions and were made in similar styles. The precise geographical origins and dates of manufacture of the former are still largely conjectural, whereas their Islamic cousins often bear informative inscriptions. Both Indian and Islamic pieces were generally made to be used as ewers (often termed aquamaniles), incense burners or, less frequently, decorative finials for oil lamps (this last function is particularly characteristic of India). Vessels in the shape of animals are significant in the arts of both regions. In the case of India, they represent a rare tradition of non-religious figurative sculpture from a period when realistically rendered figures of any kind were generally avoided in deference to Muslim religious scruples; few of these pieces have survived. In the case of the Middle East, they form virtually the only sculptural tradition that was tolerated during the Islamic period.

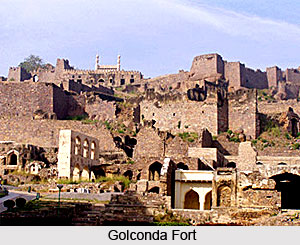

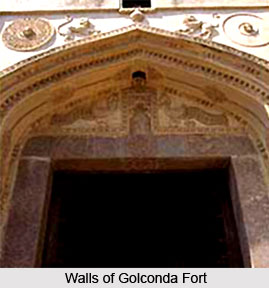

The peacock was a popular motif in all periods of Indian art. A large incense burner in the shape of this proud bird strikes a remarkable balance between the abstraction of Islam and the sculptural qualities of the Indian tradition. Made of thickly cast brass, now covered in a rich black patina, the body and neck are pierced with large holes for the escape of the sweet-smelling smoke. The comma-shaped curls on the back, tail and crest indicate a southern origin. The ancient Deccani motif, of a bird holding tiny elephants in its claws, is carved on the sixteenth-century bastions of Golconda Fort, a theme used in a second peacock incense burner.

The massively cast bronze peacock finial has none of the playfully curled plumes of the Deccan, but rather that sturdy sobriety of line associated with northern India. Indian connections can be better understood when one examines the rather small metal birds, usually parrots that surmounted the classic hanging oil lamps of Sultanate and Mughal India. The birds formed containers for the oil, and numerous examples are preserved in Indian public and private collections.

The massively cast bronze peacock finial has none of the playfully curled plumes of the Deccan, but rather that sturdy sobriety of line associated with northern India. Indian connections can be better understood when one examines the rather small metal birds, usually parrots that surmounted the classic hanging oil lamps of Sultanate and Mughal India. The birds formed containers for the oil, and numerous examples are preserved in Indian public and private collections.

The most finely proportioned bird to have survived, happily combining the abstraction of the Middle East with the plasticity of India, is the incense burner. A second peacock incense burner is conceived in a vigorous style. Its back extends into a long handle composed of an open-mouthed south Indian yali monster - the mythological leonine beast with wings, common in the south Indian repertoire and a bell-shaped support. It holds tiny elephants in its claws, an ancient Deccani motif seen on the walls of Golconda fort. Incense can be burned either inside the bird`s body or, in stick form, in the cavities at the end of its tail and in the lotus flower held aloft in the trunk of one of the small elephants. The double string of pearls around the peacock`s neck is just one of many features shared by both the burners, suggesting a common date and provenance. A third avian burner is also related in style and arrangement of parts. The handle is again a crouching, open-mouthed yali monster, but the bird perches on a round platform instead of gripping miniature elephants, and its tail does not have hollows to accommodate incense sticks.

Only a few other such objects can be assigned to this early period. A solid but roughly cast iron yali grasps tiny elephants in its claws and lassolike tail and even swallows one whole. This was doubtless fashioned in sixteenth or seventeenth-century Golconda, on the basis of its similarity to carvings on the walls of Golconda fort. It is also closely related to the incense burners: it has the same bulging eyes and ridged collar, although it lacks the necessary hollowness and opening in its back to hold the incense. Resting on a thick slab platform, it may have served as a weight in commerce: zoomorphic metal weights are known from West Africa, lion weights were used in southern Arabia, and twelfth-century Deccani lion statuettes on similar rectangular platforms, which might be weights, have recently been discovered.

Huqqas - Mughal Art

Huqqa is a triumph of design in the arena of Mughal Art. Huqqa was found in a variety of colours. The nuances of colour were surprisingly subtle: several shades of blue, from pale lilac to deep royal blue; several shades of green, yellow and white; and a unique sherry-like tan on the wings of the birds and angels. Huqqa is found in silver as well as gold. Even bidri huqqas are very common. The silver gilt huqqa dates back to the seventeenth century. Huqqas are ovoid shaped, spherical shaped and are found in a lot other shapes. It is said that the chillam of the huqqas during the Mughal period are complex in nature. Various motifs of different animals and birds are used in the chillam as well as in the huqqa.

Huqqa is a triumph of design in the arena of Mughal Art. Huqqa was found in a variety of colours. The nuances of colour were surprisingly subtle: several shades of blue, from pale lilac to deep royal blue; several shades of green, yellow and white; and a unique sherry-like tan on the wings of the birds and angels. Huqqa is found in silver as well as gold. Even bidri huqqas are very common. The silver gilt huqqa dates back to the seventeenth century. Huqqas are ovoid shaped, spherical shaped and are found in a lot other shapes. It is said that the chillam of the huqqas during the Mughal period are complex in nature. Various motifs of different animals and birds are used in the chillam as well as in the huqqa.

It has been said that huqqas were a taste of the noble men. Moreover the designs of the huqqas were to a large extent influenced by the west. The huqqas which were found in the Mughal period consisted of a round base, a chillam and cover (sarpush), an intermediate ring and a mouthpiece. The entire outer surface was covered with translucent green and blue enamel set with diamonds and rubies, and the interior is of silver but heavily gilt; the flashy effect of diamonds on dark blue differed profoundly.

Meenakari in huqqa is also well known. The meenakari work in huqqa comes in various hues and different animal motifs are used in them. The various types of Meenakari huqqa that are found are silver-gilt enamelled wash basin type huqqa, robustly proportioned silver huqqa with melon like segments. The pointed petals of the blossoms indicate a late seventeenth-century Deccani origin. A second round silver gilt huqqa has the delicate curves and exquisite decor of the early eighteenth century. Its blossom-strewn surface brings to mind painted cottons, while the unusually warm tones of white, yellow and green are the colours of imperial Mughal tile work. The round huqqas of the Mughal period resembled the silver pandans to a large extent.

Chiraghdan - Mughal Art

Chiraghdan was brought to India by way of marriage of the Mughal culture with the Indian way of life. Three distinct kinds of chiraghdan that evolved in the Sultanate and Mughal India were the tall oil lamp on a stand, the short drum- or bell-shaped candle stand, and the pillar candle stand of intermediate stature.

Chiraghdan was brought to India by way of marriage of the Mughal culture with the Indian way of life. Three distinct kinds of chiraghdan that evolved in the Sultanate and Mughal India were the tall oil lamp on a stand, the short drum- or bell-shaped candle stand, and the pillar candle stand of intermediate stature.

Sometimes during the Mughal Era chiragdaan was confused with the candle stand. But in reality they were different from each other. It has been said that oil stands were generally the gifts donated by pious sultans to the shrine tombs of important Sufi shaykhs. Such pieces usually consist of an oil reservoir at the top, which could accommodate a number of wicks; this was supported by a long narrow shaft, sometimes as much as a metre or more in length; the shaft in turn rested on a drum-like base. The whole was usually made of sheet brass and capable of being easily taken apart.

The second kind, the shamdan which was also present in Turkey and Iran besides India was the much shorter drum-shaped candle stand, designed to hold a very thick candle. In shape it was very similar to the base of the chiraghdan, and it is depicted in Mughal paintings relatively often. The third type was the tall, cylindrical pillar candle stand.

The earliest and most remarkable Indian chiraghdan is the huge lamp kept under a specially constructed domed pavilion at the shrine tomb in Ajmer of Shaykh Muin ud din Chishti, the most famous and venerated saint of the subcontinent. A 150 cm tall possibly the tallest extant chiraghdan from anywhere in the Islamic world is a proof that the Middle Eastern custom of Muslim rulers donating oil lamps to Sufi shrines extended as far as India. This grand tradition includes a Timurid or Turkman piece; such important objects as the six massive lamps commissioned by Timur in 1397 for the shrine of Shaykh Ahmad Yasavi in Turkestan, surviving fragments of which are now divided between the Louvre and the Hermitage and numerous Ottoman examples including a lamp made for the mosque in Istanbul in about 1564.

Besides these four other Indian chiraghdans are known. One has strong Indian traits: these include the succession of ridged disks on the central shaft, miniature versions of an Indian architectural element known as a kumbha, which are found frequently on Sultanate and Mughal ewers; and the rows of engraved lotus petals on the mouldings and the drip pan. The distinctive bulge above the drum-shaped base is reminiscent of early oil lamps such as the one made for Timur in 1397, and suggests a fifteenth- or early sixteenth-century date.

The Ajmer lamp is distinguished by two oil containers instead of the more customary one, each with elegant projections for wicks in the Indian manner - two features not seen in the Middle East. According to firm oral tradition going back several centuries, it was donated to the shrine as a trophy of victory in 1576 by the Mughal emperor Akbar on his triumphant return from the conquest of Bengal. The engraved cartouches and trefoils on the drum derive from the Sultanate world and suggest a date of the late fifteenth or early sixteenth century. At that time, Bihar and Bengal were in the hands of Afghan Sultans, and it may have been commissioned by one of those kings for a Muslim shrine in eastern India. It is significant that its drum-shaped base is similar to the typical Iranian shamdan known from innumerable Timurid and earlier medieval pieces, but of which only one Indian-style item has so far come to light.

Surprisingly, even though the pi-suz or mashal which is thought to be the most typical kind of Iranian lighting fixture is actually from India. Three other candle stands can be ascribed to India but not in terms of inscriptions but in terms of style.

Smaller candle stands, more suitable for lighting a house than a shrine and lacking the attachment for use as an oil lamp, are even rarer. The only one that can be assigned to pre-eighteenth-century north India is a small bronze example .Mysteriously, it fails to correspond to any of the candle stands depicted in Mughal paintings - which are usually of the pillar or drum type - but candle stand it must be, for it has the appropriate socket at the top. And Mughal it must also be, for its alternation of roses and irises beneath ogival arches is typical of ornament during the reigns of the seventeenth- century emperors. Its curious form, which incorporates the bulging shape characteristic of many Indian metal objects, may derive from a lost Hindu prototype.

A very small bidri candlestand is typical of pleasantly modest, although still very elegant, late pieces. A baluster column sits on a wide pan supported by curved legs of pronounced Deccani design, the whole soberly enlivened by a continuous pattern of serrated chevrons. Of the same general type, material and date, is covered with iris designs and has a scalloped drip pan which makes for a pretty, though minor, object.

Today majority of these oil lamps-cum-candle stands have lost their bowls, they have been erroneously considered to be simple candle stands, or torches carrying thick candles.