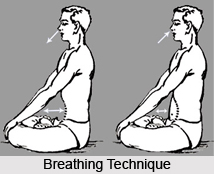

The respiratory system in human beings works involuntarily through various reflex mechanisms. The depth and the rate are maintained automatically according to the oxygen requirements of the body from moment to moment. While one brings changes in the breathing during Pranayama, the whole mechanism of breathing gets altered. With this alteration physiological changes occur during the different phases of Pranayama.

The respiratory system in human beings works involuntarily through various reflex mechanisms. The depth and the rate are maintained automatically according to the oxygen requirements of the body from moment to moment. While one brings changes in the breathing during Pranayama, the whole mechanism of breathing gets altered. With this alteration physiological changes occur during the different phases of Pranayama.

Puraka Phase

One of the phases of Pranayama is the Puraka phase. Shvas is considered to be the natural involuntary process of inspiration, regulated by the respiratory centre in the medulla oblongata. Puraka is the voluntary prolongation of the inspiratory phase. It is well controlled in terms of time, force, ventilation and depth as per the proportion. Inhalation in puraka is done in a very smooth way by keeping the force uniform. The speed at which the lungs are filled is, thus, regulated. When one increases the duration and prolongs the phase of inhalation, the force is automatically decreased. During the phase of puraka, the lungs are expanded considerably and the walls of the alveoli are stretched maximum. After a particular degree of stretching, the stretch receptors situated in the alveolar walls are stimulated. The chest continues to get expanded under cortical control. The stretch receptors are, thus, trained to withstand more and more stretching.

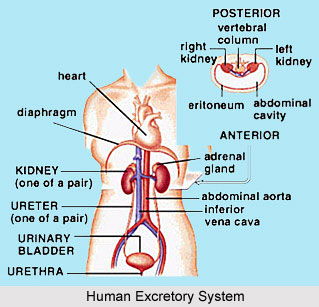

As one continues to inhale, the intra-pulmonary pressure is also raised. The diaphragm does not move freely as the abdomen is kept slightly inward and controlled. Therefore, the alveoli in the upper pulmonary part are filled with air. One uses his inspiratory capacity for prolonged phase of puraka. This has a beneficial effect on the gaseous exchange, which then works efficiently throughout the day.

During the puraka phase, which is a conscious act, the filling of the lungs is done as per one`s limit and is well attended. In order to bring necessary proportion in puraka, kumbhaka and rechaka the duration of puraka has to be well-adjusted. Thus, puraka is not merely a mechanical prolongation of inspiration but it requires full concentration of the mind as well.

Kumbhaka Phase

The second phase is the Kumbhaka phase. Kumbhaka is a voluntarily controlled suspension of breath. After a particular stage in puraka, one stops inhaling and retains the inhaled air in the lungs for a certain period of time. The intra-pulmonic pressure (in alveoli), which is raised to one`s optimum capacity, is maintained during kumbhaka stage. The alveoli and the bronchioles are stretched to their optimum level. The stretch receptors, however, cannot bring about the reflex contraction of the lungs, and the respiratory muscles cannot relax as they do normally, due to strong motor control.

The ideal duration of kumbhaka is that which would enable one to give double time for rechaka than that of puraka. The duration of kumbhaka is gradually increased over a long practice of Pranayama so that the respiratory centre is gradually acclimatized and trained to withstand higher carbon dioxide concentrations in the alveoli and in the blood.

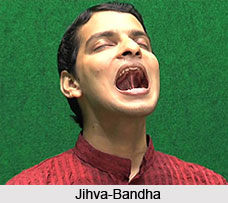

Two important principles of Pranayama are concentration and awareness. Pranayama is never done mechanically. One is expected to remain aware of `fullness` of the lungs or the pressure of the inspired air in the lungs. One may even experience the stillness in the mind or the thoughtless condition of the mind during kumbhaka. In order to avoid any functional damage to the delicate respiratory mechanism and the nerve centres, Jalandhara bandha during kumbhaka phase is usually recommended.

Two important principles of Pranayama are concentration and awareness. Pranayama is never done mechanically. One is expected to remain aware of `fullness` of the lungs or the pressure of the inspired air in the lungs. One may even experience the stillness in the mind or the thoughtless condition of the mind during kumbhaka. In order to avoid any functional damage to the delicate respiratory mechanism and the nerve centres, Jalandhara bandha during kumbhaka phase is usually recommended.

Rechaka Phase

The last phase of Pranayama is the Rechaka phase. After retaining the breath for sufficient length of time, in a comfortable manner, the Jalandhara bandha is released by moving the head up and rechaka is begun. Rechaka is a voluntarily controlled exhalation as compared to the normal exhalation (prashuas). The time (duration), force, ventilation and the flow of air are controlled in order to increase the duration of rechaka. The exhalatory force is reduced and the air is allowed to escape slowly. For this purpose, exhalation is carried out through one nostril only (as in Ujjayi, Swyabhedan or Anulom-viloma) or through both the nostrils by contracting the glottis partially at the same time (another variety of Ujjayi). Thus by creating a slight airway resistance, one can regulate the volume of air to be expelled out per unit of time. This helps in prolonging the exhalation and to reduce the force of the outgoing air. In rechaka, one uses his expiratory reserve volume for exhaling completely before starting the next puraka.

The duration of rechaka is however so adjusted that there is no feeling of `air hunger` at any stage. If it is not well adjusted in proportion, the following puraka is hurried and the whole proportion of the Pranayama is disturbed.

In short, during the practice of Pranayama one tackles all the respiratory reflexes on account of his volitional control on the respiration. The impulses from both the CNS and ANS are better integrated due to rhythmic and proportionate stimulation of the proprioceptors and visceroreceptors as well as the vagus nerve. The emotions are positively influenced due to this rhythmic and smooth breathing pattern adopted everyday. Like emotions, the mental activities are also related to breathing. As the mind is engaged fully in the breathing, unnecessary thought processes are checked. As the cognitive, intellectual and the ego-based analytical processes of the mind are minimal or even absent, the mind becomes more balanced which enables us to experience higher levels of consciousness or to get into the state of meditation as the power of concentration also increases. However, it must be remembered that Pranayama has not been developed to supply oxygen. It is meant for controlling and balancing CNS and influencing the autonomic functions as well.