The ninth yogic sutra states in details about how nirodha parinamah can be attained. It is a state where one learns to self-discipline one`s consciousness and ruminates about the silent moments. The basic theory here is to understand the relationship between the self and nature in general. And a sadhaka tries all the way to be detached from the sensory perceptions of the outer world. The threefold power (dharana, dhyana and samadhi) leads one to an absolute elevated level of consciousness, where the consciousness is able to view the diffusing light of the souls; and he achieves transformation. This transformation is nirodha parinamah. This can strictly be achieved by methods of meditation.

The ninth yogic sutra states in details about how nirodha parinamah can be attained. It is a state where one learns to self-discipline one`s consciousness and ruminates about the silent moments. The basic theory here is to understand the relationship between the self and nature in general. And a sadhaka tries all the way to be detached from the sensory perceptions of the outer world. The threefold power (dharana, dhyana and samadhi) leads one to an absolute elevated level of consciousness, where the consciousness is able to view the diffusing light of the souls; and he achieves transformation. This transformation is nirodha parinamah. This can strictly be achieved by methods of meditation.

Vyutthana emergence of thoughts, rising thoughts

nirodha suppression, obstruction, restraint

samskarayoh of the subliminal impressions

abhibhava disappearing, subjugating

pradurbhavau reappearing

nirodha restraint, suppression

ksana moment

citta consciousness

anvayah association, permeation, pervasion

nirodha restraint, suppression

parinamah transformation, effect

Study of the silent moments between rising and restraining subliminal impressions is the transformation of consciousness towards restraint (nirodha parinamah).

Transformation by restraint of consciousness is achieved by study of the silent moments that occur between the rising of impressions and one`s impulse to hold them back, and between the restraining impulse and the resurgence of thought.

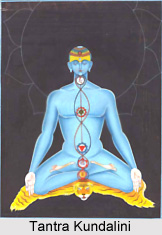

The fundamental thread of Patanjali`s philosophy is the relationship between the Self, purusa, and nature - prakrti. One is born into nature, and without it nothing would move, nothing would change, nothing could happen. One seeks to free oneself from nature in order to surpass it, to achieve lasting freedom.

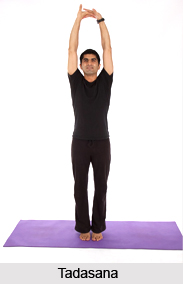

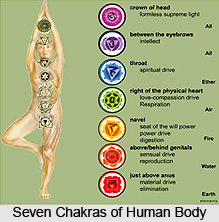

Sensory involvement leads to attachment, desire, frustration and anger. These usher in disorientation, and the eventual decay of one`s true intelligence. Through the combined techniques and resources of yama, niyama, asana, pranayama and pratyahara one learns control. These are all external means of restraining consciousness, whether one focuses on God, or the breath, or in an asana by learning to direct and disseminate consciousness. All this learning develops in the relationship between subject and object. It is relatively simple because it is a relative, dual process. A question can arise about how can subject work on subject, consciousness on consciousness. How, in other words, can one`s eyes see one`s own eyes? In III.9-15 Patanjali shows the way.

One may well ask why one ought to do this. Sutras 13 -14 answer this question and enables one to identify, within one`s consciousness, the subtle properties of nature, to discriminate between them, and to distinguish between that which undergoes the stresses and changes of time and that which is immutable and permanent. In so doing, one gains from the inner quest the same freedom from nature that one has struggled to achieve in the external. The freedom one gains from the tyranny of time, from the illusion that is absolute, is especially significant. Cutting one`s ties to sense objects within one`s own consciousness carries immensely more weight than any severance from outside objects; if this was not so, a prisoner in solitary confinement would be halfway to being a yogi. Through the inner quest, the inner aspects of desire, attraction and aversion are brought to an end.

In III.4, Patanjali shows dharana, dhyana and samadhi as three threads woven into a single, integrated, unfolding strand. Then he introduces three transformations of consciousness related directly to them, and successively ascending to the highest level, at which consciousness reflects the light of the soul. These transformations are nirodha parinama, samadhi parinama and ekagrata parinama. They are related to the three transformations in nature: dharma, laksana and avastha parinama (III. 13), resulting from one`s elevated perception, one`s penetration of nature`s reality on a higher level. The word transformation suggests to one`s imagination a series of steps in a static structure, but it is more helpful to conceive of a harmonious flux, like that offered by modern particle physics.

Nirodha parinama is associated with the method used in meditation, when dharana loses its sharpness of attention on the object, and intelligence itself is brought into focus. In dharana and nirodha parinama, observation is a dynamic initiative.

Through nirodha parinama, transformation by restraint or suppression, the consciousness learns to calm its own fluctuations and distractions, deliberate and non-deliberate. The method consists of noticing, then conquering and finally enlarging those subliminal pauses of silence that occur between rising and restraining thoughts and vice versa.

As long as one impression is replaced by a counter-impression, consciousness rises up against it. This state is called vyutthana citta, or vyutthana samskara (rising impressions). Restraining the rising waves of consciousness and overcoming these impressions is nirodha citta or nirodha samskara. The precious psychological moments of intermission (nirodhaksana) where there is stillness and silence needs to be prolonged into extra-chronological moments of consciousness, without beginning or end.

The key to understanding this wheel of mutations in consciousness is to be found in the breath. Between each inbreath and outbreath, one experiences the cessation of breath for a split second. Without this gap, one cannot inhale or exhale. This interval between each breath has another advantage - it allows the heart and lungs to rest. This rest period is called `savasana` of the heart and lungs.

The yogis who had discovered pranayama called this natural space kumbhaka, and advised humans to prolong its duration. So, there are four movements in each breath - inhalation, pause, exhalation and pause. Consciousness, too, has four movements - rising consciousness, a quiet state of consciousness, restraining consciousness and a quiet state of consciousness.

Inhalation actually generates thought-waves, while exhalation helps to restrain them (1.34). The pauses between breaths, which take place after inhalation and exhalation are akin to the intervals between each rising and restraining thought. The mutation of breath and mutation of consciousness are thus identical, because both are silent periods for the physiological and intellectual body. They are moments of void in which a sense of emptiness is felt. Sadhakas are advised by Patanjali to transform this sense of emptiness into a dynamic whole, as single-pointed attention to no-pointed attentiveness This will become the second mode - samadhi pannama.

In this process one often loses awareness on account of suppression and distraction. Having understood these silent intervals, one has to prolong them, as one prolongs breath retention, so that there is no room for generation or restraint of thoughts (Lord Krishna says in the Gita that `What is night for other beings, is day for an awakened yogi and what is night for a yogi is day for others` (11.69) This sutra conveys the same idea. When generating thoughts and their restraint keep the seeker awake, it is day for him, but night for the seer. When the seer is awake in the prolonged spaces between rising and restraining thought, it is day for him, but night for the seeker. To understand this more clearly, one can imagine the body as a lake. The mind floats on its surface, but the seer is hidden at the bottom. This is darkness for the seer. Yoga practice causes the mind to sink and the seer to float. This is day for the seer).

Just as one feels refreshed after a sound sleep, the seer`s consciousness is refreshed as he utilises this prolonged pause for rejuvenation and recuperation. But at first, it is difficult to educate the consciousness to restrain each rising thought. It is against the thought current (pratipaksa) and hence induces restlessness, while the movement from restraint towards rising thought is with the current (paksa), and brings restfulness. The first method requires force of will and so is tinged with rajas. The second is slightly sattvic, but tinged with tamas. To transform the consciousness into a pure sattvic state of dynamic silence, one must learn by repeated effort to prolong the intermissions (1.14). If no impressions are allowed to intrude, the consciousness will remain fresh, and rest in its own abode. This is ekagrata pannama.

Consciousness has three dharmic characteristics - to wander, to be restrained and to remain silent. The silent state must be transformed into a dynamic but single state of awareness. Patanjali warns that in restraint old impressions may re-emerge - the sadhaka must train to react instantly to such appearances and cut them off in their source. Each act of restraint re-establishes a state of restfulness. This is dharma pannama. When a serene flow of tranquillity is maintained without interruption, then samadhi pari-qatna and laksana pannama begin. During this phase the sadhaka may become trammeled in a spiritual desert (1.18). At this point he must persevere to reach oneness with the soul and abide in that state (avastha pannama) eternally. This final goal is reached through ekagrata pannama. (1.20.)