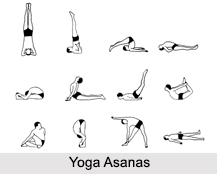

The vitarkabadhane pratipaksabhavanam sutra states about the detailed conception of yama and niyama. They are considered an integral part of yogic practice and self-realisation. However, there are also several aspects that hinder the source to reach a state of elevation. The mind here is the key, which brings forth every kind of counter thoughts and negetive aspects. Every feeling of doubt, waverings and malevolence needs to be eliminated to find a proper path to success. Some are of the view to think about an opposite situation, instead of concentrating on that negative itself. Certain asanas can be practiced with proper postures to obtain a free flow of positive thoughts.

The vitarkabadhane pratipaksabhavanam sutra states about the detailed conception of yama and niyama. They are considered an integral part of yogic practice and self-realisation. However, there are also several aspects that hinder the source to reach a state of elevation. The mind here is the key, which brings forth every kind of counter thoughts and negetive aspects. Every feeling of doubt, waverings and malevolence needs to be eliminated to find a proper path to success. Some are of the view to think about an opposite situation, instead of concentrating on that negative itself. Certain asanas can be practiced with proper postures to obtain a free flow of positive thoughts.

vitarka questionable or dubious matter, doubt, uncertainty, supposition

badhane pain, suffering, grief, obstruction, obstacles

Pranpaksa the opposite side, to the contrary

bhavanam affecting, creating, promoting, manifesting, feeling

Principles which run contrary to yama and niyama needs to be contradicted with the knowledge of discrimination.

This sutra emphasises that yama and niyama are an integral part of yoga. Sutras II.30 and 32, explains what one should stay away from doing and what one has to do.

Now the sadhaka is advised to cultivate an outlook which can oppose the current of ferocity, falsehood, stealing, non-chastity and venality, which is pratipaksa bhavana; and to go with the current of cleanliness, contentment, fervour, self-study and surrender to the Universal Spirit, which is paksa bhavana.

The principles that prevent yama and niyama needs to be counteracted with right knowledge and awareness.

When the mind is caught up in undecided ideas and actions, right perception is hindered. The sadhaka has to analyse and investigate these ideas and actions and their opposites; then only he learns to balance his thoughts by reiterated experimentation.

Some people give an objective interpretation to this sutra and maintain that if one is violent, one should think of the opposite, or, if one is attached, then non-attachment should be developed. This is the contradictory thought or pratipaksabhavana. If a person is violent, he is violent. If he is angry, he is angry. The state is not different from the fact; but instead of trying to cultivate the opposite condition, he should go deep into the cause of his anger or violence. This is paksabhava. One should also study the opposite forces with calmness and patience. Then only one develops equipoise.

Paksa means to choose a side (in an argument), to espouse one view; whereas pratipaksa communicates the idea of choosing the opposite position. A look into the physical plane will help the reader understand and experience the essence of these two words.

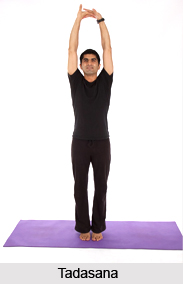

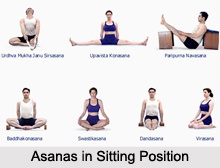

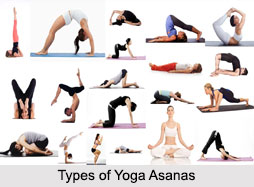

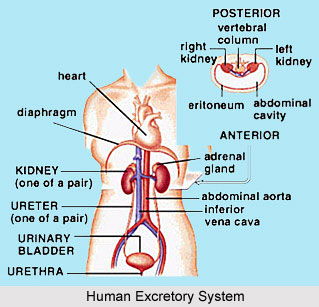

Every asana acts and reacts in its own way, cultivating health on a physical level, helping the organic systems (like the lungs, liver, spleen, pancreas, intestines and cells) to function rhythmically at a physiological level, which effects changes in the senses, mind and intellect at a mental level. While practising the asana, the sadhaka must carefully and minutely observe and adjust the position of the muscles, muscle fibres and cells, measuring lightness or heaviness, paksa or pratipaksa, as required for the performance of a healthy and well-balanced asana. He thus adjusts tunefully the right and left sides of the body, the front and the back. Learning to interchange or counterpoise the weaker with the intelligent side gives rise to changes in the sadhaka - he grows, able to observe equipoise in the body cells and the lobes of the brain; and calmness and sombreness in the mind. Therefore the qualities of both paksa and pratipaksa are attended to. By elevating the weak or dull to the level of the intelligent or strong, the sadhaka learns compassion in action.

In pranayama, too, one focuses on the consciousness on the various vibrations of the nerves with the moderated flow of in breath and out breath, between the right and left sides of the lungs and also between the right and left nostrils. This adjustment and observation in the practice of yoga merges paksa and pratipaksa, freeing one from the turbulences of wrath and hopelessness, which are substituted by hope and emotional stability.

The internal measuring and balancing process, which is called paksa prati-pahsa, is in some respects the answer to why yoga practice actually works, why it has mechanical power to revolutionise the whole being. This is precisely why asana is not gymnastics, why pranayama is not deep breathing, why dhyana is not self-induced trance, why yama is not just morality. In asana for instance, the pose first brings inner balance and harmony, but in the end it is simply just the outer expression of inner harmony.

One is always taught these days that the miracle of the world`s eco-system is its balance, a balance which modern man is fast ruining by deforestation, pollution, over-consumption. This is because when man becomes unbalanced, he attempts to change not himself but his environment, with the purpose to create the illusion that he is enjoying health and harmony. In winter he overheats his house, in summer he freezes it with air-conditioning. This is not stability, but haughtiness. Some people consume tablets to go to sleep and tablets to wake up. It is a life like a ping-pong ball. The learner of yoga who learns to balance himself internally at every level, physical, emotional, mental, by observation of paksa and pratipaksa, liberates himself from this diabolical `to-ing` and `fro-ing` and lives in synchronisation with the natural world. As he is stable, he can accustom himself to outside changes. The flexibility one obtains in asana is the living symbol of the litheness one gains in relation to life`s struggles and challenges.

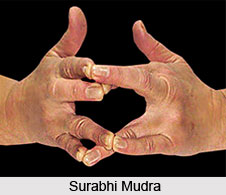

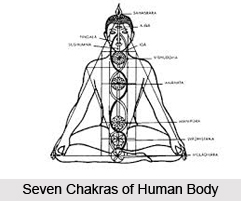

Through paksa and pratipaksa one can balance the three energetic currents - ida, pihgala and susumna, the three principal nadis, or channels of energy. One can imagine the calf muscle as it is extended in Trikonasana, the Triangle Posture. Initially the outer calf surface may be active or awake on one side, dull on the other, and its absolute centre completely unaware. Then one learns to stretch in such a way as to bring the surplus energy of ida equally to pihgala and susumna or vice versa. So there is an equal and agreeable flow of energy in the three channels.

Likewise, learning to maintain precision and composure of intelligence in body, mind, intellect and consciousness through meditation is the remedy for uncertain knowledge. To obtain this state in meditation, yama and niyama needs to be cultivated. Success or failure at higher levels of consciousness depends upon yama and niyama. This fusing of paksa and pratipaksa in all aspects of yoga is true yoga.

Here, it needs to be emphasised that yama and niyama are not only the foundation of yoga, but also the reflection of one`s success or failure at its higher levels. For example, a successful `godman` who is adept in meditation - if he sloppily lets himself down in yama and niyama, he nullifies his claim to spirituality.