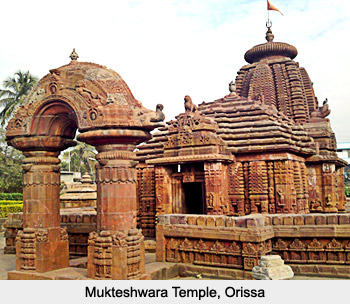

History of Deccan sculpture dates back to the Pallavas which presented a unification of both north and south Indian temple architectures. Precisely speaking this became the basic feature of Deccan sculpture with its inimitable provincial elements. The many temples built under the early Western Chalukyas between the end of 6th century and the end of the 8th offer significant landmarks in the maturation of the Hindu temple. The Nagara kind has a `tower` or shikhara of layer on layer of kapotas and gavasaka courses, crowned by a huge amalaka and with smaller ones inset at the nooks. The Dravida has increasingly smaller storeys encircled by small pavilions and coronated by a dome (shikhara) above a narrower throat.

History of Deccan sculpture dates back to the Pallavas which presented a unification of both north and south Indian temple architectures. Precisely speaking this became the basic feature of Deccan sculpture with its inimitable provincial elements. The many temples built under the early Western Chalukyas between the end of 6th century and the end of the 8th offer significant landmarks in the maturation of the Hindu temple. The Nagara kind has a `tower` or shikhara of layer on layer of kapotas and gavasaka courses, crowned by a huge amalaka and with smaller ones inset at the nooks. The Dravida has increasingly smaller storeys encircled by small pavilions and coronated by a dome (shikhara) above a narrower throat.

Chalukya Sculpture

The amalgamated trait of these temples is also apparent in particular facets of the early western Chalukya mandapa. These are connected to the front of the shrine proper, in alignment with one or two of the temples, alone allows one to glimpse a pretty long period of progress, a supposition to which the breakthrough of the remains of a brick pillared hall of probably Satavahana date, lends weight. Even so, the type has fractional parallels of early date elsewhere.

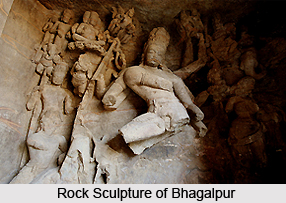

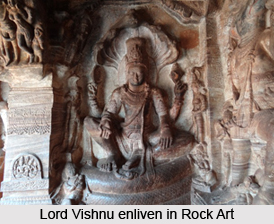

Buddhist doings have been discovered in Badami and Aihole, which possibly belong to the 6th century. These findings include the earliest excavated cave temples, structural temples, and sculpture for which there is more than excavated or secondary evidence, correspond with the accession to power of the early Western Chalukya Dynasty in the mid 6th century, and are principally Hindu with a splashing of Jain monuments. The early Western Chalukya temples can be separated into those of the late 6th, 7th and perhaps early 8th centuries in three diverse sites- Badami (ancient Vatapi), Aihole (ancient Ayyavolt) and Mahavira; and a `second generation` in the succeeding century, including some far bigger than any that had gone before, at Piratical. The classes are not absolute, and some temples in Aihole belong to the early 8th century. There are also the rock-cut Hindu and Jain temples at Badami, one of them (Cave III) an art-historical milestone because, alone among the caves, it is dated (578), and the lesser but equally exquisite cave-temples in Aihole, all with remarkable Deccan sculpture.

Buddhist doings have been discovered in Badami and Aihole, which possibly belong to the 6th century. These findings include the earliest excavated cave temples, structural temples, and sculpture for which there is more than excavated or secondary evidence, correspond with the accession to power of the early Western Chalukya Dynasty in the mid 6th century, and are principally Hindu with a splashing of Jain monuments. The early Western Chalukya temples can be separated into those of the late 6th, 7th and perhaps early 8th centuries in three diverse sites- Badami (ancient Vatapi), Aihole (ancient Ayyavolt) and Mahavira; and a `second generation` in the succeeding century, including some far bigger than any that had gone before, at Piratical. The classes are not absolute, and some temples in Aihole belong to the early 8th century. There are also the rock-cut Hindu and Jain temples at Badami, one of them (Cave III) an art-historical milestone because, alone among the caves, it is dated (578), and the lesser but equally exquisite cave-temples in Aihole, all with remarkable Deccan sculpture.

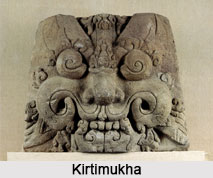

The quite fertile sculpture of the `first generation` early western Chalukya temples is in a combination of styles, whose origins or parallels are to be found outside the region, proved with strong indigenous element, twinning the architecture but with no big relationships with it. Mysteriously enough, the two fine murtis of the Maleg Shivalaya are very close to early post-Gupta sculpture in the north- principally naturalistic, yet over stylish and somewhat unashamedly assertive. Weapons and symbols are assertively individual, the attendees elegantly mannered in the best Gupta tradition. A gentler and quite appealing early post-Gupta fashion marks the mithunas in temples as varied as the Lad Khan and the Durga. There is an irregular folk element, for instance, in the admired Asvamukha pillar sculptures, where the formal horse-headed yaksa is rowdily approached by the male figurine or stands modestly beside him.

The quite fertile sculpture of the `first generation` early western Chalukya temples is in a combination of styles, whose origins or parallels are to be found outside the region, proved with strong indigenous element, twinning the architecture but with no big relationships with it. Mysteriously enough, the two fine murtis of the Maleg Shivalaya are very close to early post-Gupta sculpture in the north- principally naturalistic, yet over stylish and somewhat unashamedly assertive. Weapons and symbols are assertively individual, the attendees elegantly mannered in the best Gupta tradition. A gentler and quite appealing early post-Gupta fashion marks the mithunas in temples as varied as the Lad Khan and the Durga. There is an irregular folk element, for instance, in the admired Asvamukha pillar sculptures, where the formal horse-headed yaksa is rowdily approached by the male figurine or stands modestly beside him.

Early Western Chalukya architecture reached the culmination of its second phase at Pattadakal. Queerly enough, of the four large temples constructed here in the first half of the 8th century, only one- the Papanatha, is Nagara, despite the prevalence of the type at Alampur, a 150 miles to the east. The three other temples are ingenuously Dravida. The earliest, called the Sangamesvara or Sri Vijayesvara after its constructor, Vijayaditya Satyasraya (696-733), does not even have a nasika, reverberating the non existence of an antechamber in the sanctum, whose walls are extraordinarily thick. The mandapa has moderately disappeared. From the outset, the luxuriously ornamented interiors of the temples of the Deccan drew upon their own cave convention and eventually on Gupta references, rather than upon Tamil Nadu, where, until a very late date, interiors are severely bare.

Rashtrakuta Sculpture

Rashtrakuta Sculpture

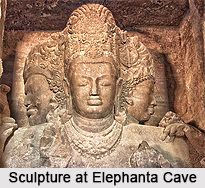

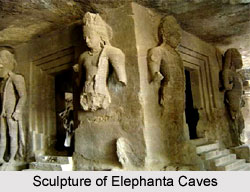

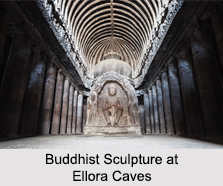

Rock cut caves at Ellora were also one of the common temple architecture in ancient Deccan. The sculpture of Kailasanatha temple is worth checking out. The unification of the north and south Indian temple features is evident in this temple architecture.

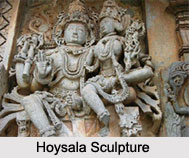

The early Rashtrakutas carried the technique into northernmost Deccan, but there is so far no verification of any structural temples there in the `southern` fashion of their grand rock-cut works in Ellora. Nor did this style continue as such even in central Karnataka, where so many excellent Dravidian temples had been erected under the early Western Chalukyas. By the end of 8th century, the origin could already be comprehended of Karnataka`s distinctive contribution to Indian temple architecture, which concluded in the later Hindu period, in the Hoysala fashion.

The outlasting shrines of the 9th and 10th centuries in southern Karnataka, generally linked with the Gangas, a local dynasty, are roughly provincial editions of late Pallava and early Chola types. These are well constructed, unblemished, but rather bleak, with a scarcity of external recess sculptures, despite some delicate images inside. In Kolar district to the east, the Ramesvara in Avani, incorporates four shrines, all but one with its own mandapa, and all but one side-by-side.

The outlasting shrines of the 9th and 10th centuries in southern Karnataka, generally linked with the Gangas, a local dynasty, are roughly provincial editions of late Pallava and early Chola types. These are well constructed, unblemished, but rather bleak, with a scarcity of external recess sculptures, despite some delicate images inside. In Kolar district to the east, the Ramesvara in Avani, incorporates four shrines, all but one with its own mandapa, and all but one side-by-side.

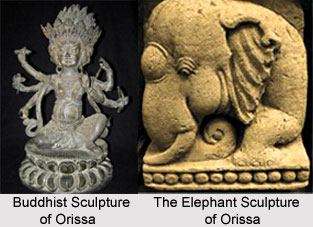

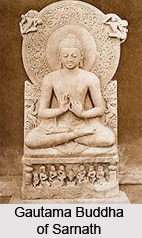

Pallava Sculpture

Pallava sculpture has been highly influenced by Buddhist tradition. On the whole it is more monumental and linear in form avoiding the typical ornamentation of the Deccan sculpture. The free standing temples at Aithole and Badami in the Deccan and the Kanchipuram and Mahabalipuram in the Tamil country provided a better background for sculpture than the rock-cut temples. The Pallava sculpture was monumental and linear in form resembling the Gupta sculpture. Although the basic form was derived from the older tradition, the end result clearly reflected its local genius.

Chola Sculpture

The Cholas had built a strong foundation of sculpted architecture in 850 -1250 CE. They refined the styles of Dravidian art and created intricate bronze and stone sculptures and temples. Several temples were built by Rajendra Chola and his son; Rajendra Chola I. These temples were of a very intricate and detailed design.