Introduction

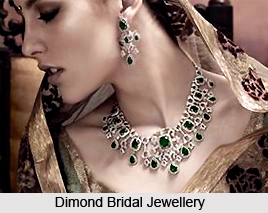

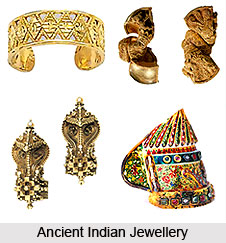

History of Indian jewellery has inspired modern and contemporary jewellery designers to introduce unique and intricate styles in the modern-day jewelleries. Ornaments in the country have undergone several transformations, under the cultural influence and reign of different dynasties and periods for a period of over 5000 to 8000 years. India is believed to possess one of the most ancient historical legacies of crafting jewelleries, which can be traced back to the era of Ramayana and Mahabharata. Jewelleries proved to usher in financial prosperity for India since the abundant quantity of jewel resources permitted India to utilize them as a significant form of exchange and export with foreign countries. The earliest form of jewellery discovered in the Indian continent, are described as ancient jewellery. The ancient jewellery of India includes a large variety of earrings, beads, amulets, seals, amulet cases, necklaces, and much more.

History of Indian jewellery has inspired modern and contemporary jewellery designers to introduce unique and intricate styles in the modern-day jewelleries. Ornaments in the country have undergone several transformations, under the cultural influence and reign of different dynasties and periods for a period of over 5000 to 8000 years. India is believed to possess one of the most ancient historical legacies of crafting jewelleries, which can be traced back to the era of Ramayana and Mahabharata. Jewelleries proved to usher in financial prosperity for India since the abundant quantity of jewel resources permitted India to utilize them as a significant form of exchange and export with foreign countries. The earliest form of jewellery discovered in the Indian continent, are described as ancient jewellery. The ancient jewellery of India includes a large variety of earrings, beads, amulets, seals, amulet cases, necklaces, and much more.

Ancient History of Indian Jewellery

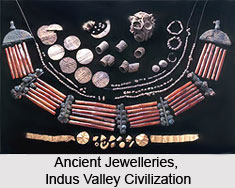

Numerable parts of Indus Valley Civilization, which represented regions of the current-day Pakistan and north-western portions of India were known for producing memorable masterpieces of jewelleries. People belonging to this ancient Indian civilization were quite fond of flaunting different types of jewelleries, which is evident from the statues of this era. Metallic bangles, bead neckpieces, gold necklaces and beautiful gold earrings were manufactured within 1500 BC. Bead ornaments were favoured prior to 2100 BC, since at this point of time the utility of metals was not fully realised. Simple procedures were incorporated to create astonishing pieces of bead jewellery in those times, which also involved introducing Persian motifs in ancient ornaments. Some of these ornaments exuded a charm typical to jewelleries utilized by the Hindus. However, during Indus Valley Civilization, jewelleries were more popular amongst the womenfolk who loved wearing shell or clay bracelets which were resembled doughnuts and were black.

Gold rings, brooches, gold chokers, earrings, necklaces and gold bands worn on the foreheads were in high demand, while some of the men wore beads. Tiny beaded jewels were employed to adorn the hair of men and women, which measured about one millimetre in length. A special bracelet known as `kada` is frequently used in the country, since times immemorial, and its patterns were inspired by elephants, peacocks and other beasts. Hindus have always believed that metals like silver and gold are holy since gold signifies the warmth of the Sun God or Lord Surya and silver represents the calmness of the moon. Since pure gold is never corroded with time, Hindu traditions prioritize the usage of gold and relate gold with the concept of immortality. Gold jewelleries are mentioned in ancient Indian literature.

Gold rings, brooches, gold chokers, earrings, necklaces and gold bands worn on the foreheads were in high demand, while some of the men wore beads. Tiny beaded jewels were employed to adorn the hair of men and women, which measured about one millimetre in length. A special bracelet known as `kada` is frequently used in the country, since times immemorial, and its patterns were inspired by elephants, peacocks and other beasts. Hindus have always believed that metals like silver and gold are holy since gold signifies the warmth of the Sun God or Lord Surya and silver represents the calmness of the moon. Since pure gold is never corroded with time, Hindu traditions prioritize the usage of gold and relate gold with the concept of immortality. Gold jewelleries are mentioned in ancient Indian literature.

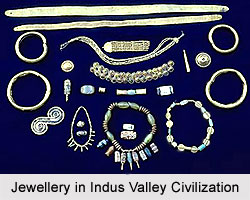

Jewellery in Indus Valley Civilization

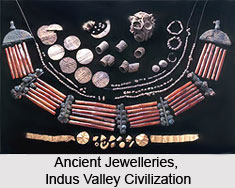

Jewellery in Indus Valley Civilization is amongst the most commonly found relics and artefacts of the Harappan society. The traditional art of India recommends a richness and profusion in the jewellery adorned by both men and women during that period. Earlier, it had a massive quantity to it but the workmanship was coarse. Ornaments made of gold, silver, copper, ivory, pottery and beads have been discovered in civilisations as ancient as the Harappa and Mohenjodaro. The people of the Indus Valley Civilization were the first to explore the jewellery making craft. One of the most remarkable excavations of Indus Valley Civilisation was the discovery of the art and crafts and the social, religious and economic condition of that era.

Jewellery in Indus Valley Civilization is amongst the most commonly found relics and artefacts of the Harappan society. The traditional art of India recommends a richness and profusion in the jewellery adorned by both men and women during that period. Earlier, it had a massive quantity to it but the workmanship was coarse. Ornaments made of gold, silver, copper, ivory, pottery and beads have been discovered in civilisations as ancient as the Harappa and Mohenjodaro. The people of the Indus Valley Civilization were the first to explore the jewellery making craft. One of the most remarkable excavations of Indus Valley Civilisation was the discovery of the art and crafts and the social, religious and economic condition of that era.

The excavations yielded a rich collection of objects in stone, bronze and terracotta. One of the most known figurines is perhaps the Dancing girl of Mohenjodaro (in bronze) wearing a necklace and a series of bangles almost covering one arm, her hair dressed in a complicated coiffure, standing in a provocative posture, with one arm on her hip and one lanky leg half bent.

Types of Jewellery Designs : By 1,500 BC the population of the Indus Valley was creating moulds for metal and terracotta ornaments. Gold jewellery from these civilizations also consisted of bracelets, necklaces, bangles, ear ornaments, rings, head ornaments, brooches, girdles etc. Here, the bead trade was in a full swing and they were made using simple techniques. Although women wore jewellery the most, some men in the Indus Valley wore beads. Small beads were often crafted to be placed in men and women`s hair. The beads were so small they usually measured in at only 1 mm long.

Both men and women adorned themselves with ornaments. While necklaces, fillets, armlets and finger-rings were common to both genders; females wore jewellery in the Indus Valley predominantly, since they wore numerous clay or shell bracelets on their wrists. They were often shaped like doughnuts and painted black. Over the time, clay bangles were discarded for more durable ones. Women wore girdles, earrings and anklets.

Ornaments were made of gold, silver, copper, ivory, precious and semi-precious stones, bones and shells etc. Other pieces that women frequently wore were thin bands of gold that would be worn on the forehead, earrings, primitive brooches, chokers and gold rings. Even the necklaces were soon adorned with gems and green stone.

Medieval History of Indian Jewellery

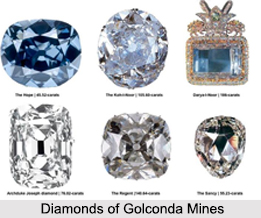

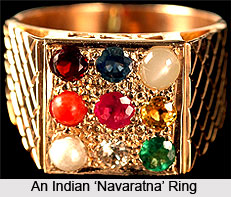

Medieval India witnessed the utility of a large variation of jewelleries, particularly the period between the 16th to 19th centuries. Indian jewelleries played a crucial role especially in the Indian royalty and it enabled the establishment of many administrative laws. Women were entitled to wear gold jewels on their feet only if they received an official permission and also womenfolk belonging to the royalty. Rulers or `Maharajas` were more deeply associated to various kinds of magnificent jewelleries, though jewels were also very common amongst the general masses of the country. The `Navaratna` or nine-gem studded ornament was amongst a significant jewellery which was highly popular amongst Maharajas. The Navaratna gem comprised an amulet composed of red zircon or `hyacinth`, diamond, coral, cat`s eye, sapphire, ruby and pearl. It is said that each of these precious stones symbolised a celestial deity, and diamond is considered the strongest Indian gemstone. The gemstones of this jewel used to be available in various cuts and sizes, and were revered by the family members of royal dynasties as Hindu Gods.

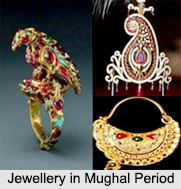

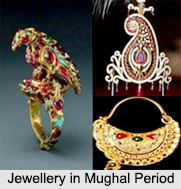

Jewellery in Mughal Period

Jewellery in Mughal Period included a variety of ornaments of adornment which were greatly influenced over time. These include necklaces, rings, earrings and a whole lot of other items made of precious stones and gems. During the Mughal rule in India, which began in the 16th century, the art of jewellery making flourished. The Mughal treasury was one of the fullest and best endowed in all of Indian history, and therefore jewellery too must have occupied a place of prominence. Wearing expensive jewellery marked one"s position. The talent and tradition for fine and artistic craftsmanship, coupled with a wealthy and active class of patrons, has also been responsible in shaping Mughal jewellery.

Jewellery in Mughal Period included a variety of ornaments of adornment which were greatly influenced over time. These include necklaces, rings, earrings and a whole lot of other items made of precious stones and gems. During the Mughal rule in India, which began in the 16th century, the art of jewellery making flourished. The Mughal treasury was one of the fullest and best endowed in all of Indian history, and therefore jewellery too must have occupied a place of prominence. Wearing expensive jewellery marked one"s position. The talent and tradition for fine and artistic craftsmanship, coupled with a wealthy and active class of patrons, has also been responsible in shaping Mughal jewellery.

Several Influences on Mughal Jewellery : Various artefacts have been excavated that show the adaptability of both conventional Islamic and traditional Indian styles along with the originality and creativity of artists in various regions. Other than the Mughals, other Islamic powers have also dominated India, which include the Ghaznavids, the Ghurids, the Turkish and Afghan dynasties. Thus the culmination of centuries of Islamic rule was seen in the Mughal dynasty and all these collective influences were witnessed in their life, art, architecture and crafts, including jewellery.

Influence of Rajputs on Mughal Jewellery :  Some of the finest goldsmiths worked under the Mughal patronage. Rajasthan undoubtedly contributed a great deal to the formation of the hybrid Mughal style, as Rajput princesses married Mughal royalty and its rulers had taken high positions at court, both bringing their jewellery and, probably, their craftsmen with them. As a result, Mughal jewellery was influenced by the Rajputs, and thus began the combination of Rajput quaint craftsmanship and Mughal delicate artistry.

Some of the finest goldsmiths worked under the Mughal patronage. Rajasthan undoubtedly contributed a great deal to the formation of the hybrid Mughal style, as Rajput princesses married Mughal royalty and its rulers had taken high positions at court, both bringing their jewellery and, probably, their craftsmen with them. As a result, Mughal jewellery was influenced by the Rajputs, and thus began the combination of Rajput quaint craftsmanship and Mughal delicate artistry.

European Influence on Mughal Jewellery

Some of the earliest Mughal jewellery shows the gradual influence of the 17th Century European style. Jewellery in the Renaissance era also hugely influenced the Mughal pattern, such as the scrolling leaf designs on the inner surface of a thumb ring. A more prominent imposition is evident in turban jewellery where a completely new form seems to have its source in European hat aigrettes. Courtly jewellery carried on the traditions established in the 17th century.

Styles of Mughal Jewellery : The styles in jewellery under the Mughals were an amalgamation of Islamic and Hindu artistic styles. The style of jewellery in Akbar"s era was a hybrid of Iranian and Hindu influences, as would be expected of the emperor of a dynasty whose cultural roots were in Iran. The turban plume known as "Kalgi" or "Figha" and golden bands called "Sarpich" are exactly those seen in contemporary Safavid painting. His necklaces on the other hand are of the kinds listed in Kautilya"s Arthashastra , consisting of pearls, pearls and gems, gold on its own, or gold with pearls and gems. A contemporary work, the Ain-i-Akbari, gives a list of ornaments worn by the women of Hindustan. Some of these may be seen virtually unchanged and worn equally by Muslim ladies. The ornaments include the "Karanphul" which is shaped like the blossom of love-in-the-mist and "Nath", a nose ring in the form of a circular gold wire threaded with a ruby between two pearls or other gemstones.

Evolution of Mughal Jewellery :  Under the rule of Jahangir, fashions at court had undergone a dramatic transformation as can be seen in the paintings of Jahangir. Akbar followed the Iranian fashion by having his upright feather plume at the front of the turban. Jahangir introduced his own, softer, style with the plume weighted down with a large pearl.

Under the rule of Jahangir, fashions at court had undergone a dramatic transformation as can be seen in the paintings of Jahangir. Akbar followed the Iranian fashion by having his upright feather plume at the front of the turban. Jahangir introduced his own, softer, style with the plume weighted down with a large pearl.

Later, Shah Jahan, his son, turned to Europe for an innovative Jigha, which related to the designs of the Dutch jeweller Arnold Lulls. Shah Jahan was greatly impressed by the also jewels wore by James I, as depicted in the portraits brought to the court by Sir Thomas Roe. In the 1618 painting, Shah Jahan, still a prince holds an Indian version of Lulls` designs.

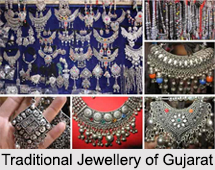

The Mughal emperors conquered most of India, and as a result, their influence extended well beyond North India. The typical Mughal style is visible in the jewellery of Madhya Pradesh, Gujarat, Andhra Pradesh and Odisha. Mughal enamelling and stonework were adopted by other Indian regions for their regional jewellery. Following the Mughals, their style of jewellery-making was carried forward and indulged in by the successive Indian rulers as well.

Jewellery in Gandhara Period

Of the relatively rare finds of ancient gold jewellery, most are from the north west of the subcontinent, the region known as Gandhara in ancient times, and particularly from Taxila, a flourishing city since the fourth century BC and which has been extensively excavated. Most of this jewellery shows a strong Greek or Hellenistic influence. Earrings often consist of discs from which hang down tiny chains terminating in beads or sometimes-small gold-erotes, or cupids, in repousse. Such pendants also hang down over almost their whole length from necklaces when they are of the `strap` variety. Ribbing is practised, sometimes for the terminal elements of necklaces, but spherical ribbed beads, found in considerable numbers, appear to be an Indian type. Pairs of heavy round tubular bracelets of a purely Indian type were also found at Taxila, of the type worn by the yakshi from Tamluk. Of the early sculpture figures, which have survived, none wears as much or as sumptuous jewellery as this yakshi on a moulded terracotta plaque found at Tamluk near Calcutta, of 200 century BC.

Of the relatively rare finds of ancient gold jewellery, most are from the north west of the subcontinent, the region known as Gandhara in ancient times, and particularly from Taxila, a flourishing city since the fourth century BC and which has been extensively excavated. Most of this jewellery shows a strong Greek or Hellenistic influence. Earrings often consist of discs from which hang down tiny chains terminating in beads or sometimes-small gold-erotes, or cupids, in repousse. Such pendants also hang down over almost their whole length from necklaces when they are of the `strap` variety. Ribbing is practised, sometimes for the terminal elements of necklaces, but spherical ribbed beads, found in considerable numbers, appear to be an Indian type. Pairs of heavy round tubular bracelets of a purely Indian type were also found at Taxila, of the type worn by the yakshi from Tamluk. Of the early sculpture figures, which have survived, none wears as much or as sumptuous jewellery as this yakshi on a moulded terracotta plaque found at Tamluk near Calcutta, of 200 century BC.

Different types of jewellery are so far found in these excavations. These include the strings of beads dangling from her girdle and below; the former even have pendants in the form of small squatting figures. From the discs at the ends of the massive earrings hang, fringe-like, small strings of beads, and part of her girdle is composed of round ribbed beads. The long pins stuck into her headdress are headed, not by figures but by auspicious symbols, such as the trident and the elephant god. The most intricate piece of jewellery depicted, however, hardly visible to the naked eye, is the clasp to the bandolier across the goddess`s chest composed of a deer and a makara (a semi-aquatic mythical beast which plays an important part in Indianiconography). It is quite likely that in the real thing they would have been covered with granulation).

The characteristic sculpture of Gandhara during the first three or four centuries AD was produced, in vast quantities, for the Buddhists and their monasteries. Consequently, with the notable exception of Hariti, the figures with adornments are all masculine Bodhisattvas, decked in the finery of a local magnate (the Buddha, of course, wears no jewellery of any kind until much later). These favoured massive earrings, armlets and torques, often incorporating bird or animal forms. On their diadems and armlets can sometimes be seen the high-hunched animals of the Animal Style. Similarly one or two examples, possibly imports, of the Sarmatian and Scythian jewellery from Southern Russia have been found in India. On the other hand, there are examples of the tubular reliquaries almost invariably strung along the yajnopavitas (sacred thread) of the Bodhisattvas. First after the Gupta period (550 AD), the jewellery portrayed on statues becomes increasingly conventionalized and removed from the actual practice.

About the middle of the fifth century, Gandhara was conquered by groups of Chinese tribe often identified as the Huns or Hephthalites, thus bringing this major period of Buddhist patronage to a close. Still, a handful of ornaments attest to an ongoing Buddhist presence in Gandhara during the following centuries. A late sixth-century Buddha structure is a good example of the perpetuation of Gandharan-style images. However, important adjacent Buddhist communities continued to thrive in the Swat valley, Kashmir, and Afghanistan. Not surprisingly, sculptural production seen in the Kabul valley of Afghanistan follows the artistic tradition originally established in Gandhara Art. Like the monumental Gandharan torso, the sculpture found at Afghan sites such as Hadda, including a head of a Bodhisattva is quite naturalistic. Still, the inset garnet eyes and elaborate hairstyle are elements not seen in Gandhara, but rather are an expression of Afghan taste.

Ultimately, however, the stylistic roots of Buddhism in north India are reflected in another head from the site of "Hadda" that takes on the formal stylized features of Gupta-period images found in the Ganges River basin. The taste for classical forms eventually fades and by the eighth century, with the coming of Islam, the Buddhist tradition comes to an end in Afghanistan.

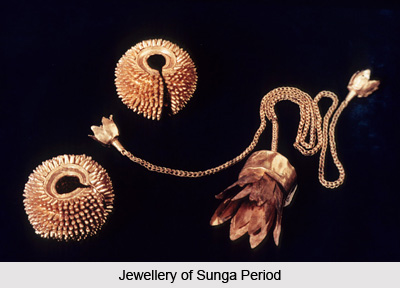

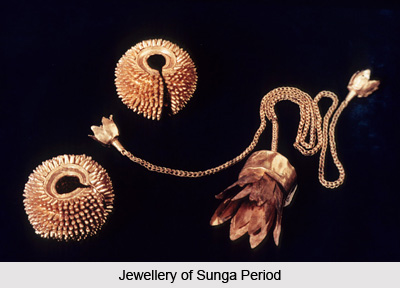

Jewellery of Sunga Period

Later, due to the advent of the Sunga dynasty, the jewellery became a little refined. In the sculptures of the period references show us that the material used most frequently were gold and precious stones like corals, rubies, sapphires, agates, and crystals. Pearls and beads of all kinds were used plentifully including those made of glass. Certain ornaments were common to both sexes, like earrings, necklaces, armlets, bracelets and embroidered belts. Apart from these forms of jewellery, the only material evidence of a piece of Mauryan jewellery is a single earring found at Taxila dated second century BC, which is similar to Graeco-Roman and Etruscan Jewellery. They are as follows:

Later, due to the advent of the Sunga dynasty, the jewellery became a little refined. In the sculptures of the period references show us that the material used most frequently were gold and precious stones like corals, rubies, sapphires, agates, and crystals. Pearls and beads of all kinds were used plentifully including those made of glass. Certain ornaments were common to both sexes, like earrings, necklaces, armlets, bracelets and embroidered belts. Apart from these forms of jewellery, the only material evidence of a piece of Mauryan jewellery is a single earring found at Taxila dated second century BC, which is similar to Graeco-Roman and Etruscan Jewellery. They are as follows:

Earring (Karnika): These were of three types viz, a simple ring or circle called Kundala, a circular disc earring known as dehri and earrings with a flower-like shape known as Karnaphul.

Necklaces: These were also of two kinds; a short one called Kantha, which was broad and flat, usually gold, inlaid with precious stones, and a long one, the lambanam. These chain or bead necklaces were sometimes three-to-seven stringed and were named after the number of strings of which they were composed. At the centre of each string of beads was an amulet for warding off evil forces.

Armlets (Bajuband): These were of gold and even the armlets made of silver beads were worn on the upper arm, and were occasionally studded with precious stones.

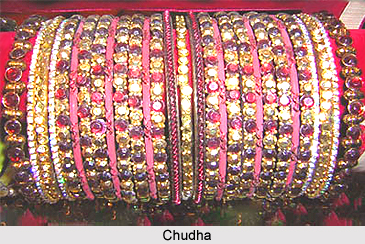

Bracelets (Kangan): These were very often made of square or round beads of gold, and richly embroidered cloth belts completed the male ensemble.

Girdle (Mekhala): Women, in addition, wear girdles called mekhala, a hip belt of multi-stringed beads, originally made from the red seed kaksha.

Anklets & Rings: All women also wore anklets and thumb and finger rings. The rings were plain and crowded together on the middle joints of the fingers. Anklets were often of gold in this period, though silver was more common. They could be in the form of a simple ring, Kara, a thick chain, sankla, oran ornamental circle with small bells called ghungru.

Forehead Ornaments: Forehead ornaments for women were quite common and worn below the parting of the hair and at the center of the forehead. These consisted of thin plate of gold or silver stamped in various patterns, as well as a star-shaped sitara and bina. And a tiny ornament called bindi.