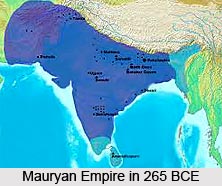

Ashoka ascended the throne of Magadha as a successor of Bindusara in 273 B.C. Since his ascension to the throne, Ashoka was popular among his subjects as a benevolent king. However the greatness of Ashoka as a king lies in his huge conquests. Ashoka had his own policy of conquest for which the Mauryan Empire extended to a large extent during his reign. During the first thirteen years of his reign, Ashoka followed the traditional Mauryan policy of aggressive imperialism and the annexation and extension of empire within India. The second strategy he followed was the strong appeasing relation with the non-Indian powers by exchanging envoys and appointing the Yavana officials as his governor. With this shrewd diplomacy he wanted to strengthen his own empire against foreign invasion. This strategic step by Ashoka was considered by the historians in the later ages as one of his astute policy of conquests. Though it has been opined by the historians that Ashoka followed in the footsteps of his predecessors, there is no surviving historical documents about the conquests of Ashoka. In his rock edicts he had only depicted his conquests in Kalinga. Therefore the historians have unanimously opined that throughout his life Ashoka had made only one conquest.

Ashoka ascended the throne of Magadha as a successor of Bindusara in 273 B.C. Since his ascension to the throne, Ashoka was popular among his subjects as a benevolent king. However the greatness of Ashoka as a king lies in his huge conquests. Ashoka had his own policy of conquest for which the Mauryan Empire extended to a large extent during his reign. During the first thirteen years of his reign, Ashoka followed the traditional Mauryan policy of aggressive imperialism and the annexation and extension of empire within India. The second strategy he followed was the strong appeasing relation with the non-Indian powers by exchanging envoys and appointing the Yavana officials as his governor. With this shrewd diplomacy he wanted to strengthen his own empire against foreign invasion. This strategic step by Ashoka was considered by the historians in the later ages as one of his astute policy of conquests. Though it has been opined by the historians that Ashoka followed in the footsteps of his predecessors, there is no surviving historical documents about the conquests of Ashoka. In his rock edicts he had only depicted his conquests in Kalinga. Therefore the historians have unanimously opined that throughout his life Ashoka had made only one conquest.

Ashoka invaded Kalinga in the 8th year of his reign calculated from the period of his coronation and continued this aggressive imperialism in Kalinga till his tenth year. The Kalinga country corresponds to modern Orissa and Ganjam district. Though the causes which prompted Ashoka to campaign against Kalinga is not mentioned in clear terms in any of the contemporary historical documents, yet it was supported by the rock edicts and inscriptions that Kalinga was a part of the Magadhan Empire during the reign of the Nandas. This poses a controversial question among the historians that what made Ashoka to reconquer the territory of Kalinga. According to H.C. Roychowdhury, Kalinga asserted its independence and revolted against Bindusara but Pliny refuted the view of Roychowdhury completely and asserted that Kalinga was an independent province during the reign of Chandragupta Maurya. Hence there is no question of its revolt against Bindusara. Dr. R.S Tripathy has aptly pointed out that Kalinga was free during the reign of Chandragupta Maurya. Since Chandragupta was busy with his preoccupations in North India, he did not have time to reconquer the province of Kalinga. Hence the province was independent. However the statement of Dr. Tripathy happens to be the satisfactory explanation in this respect. Dr Tripathy furthermore adds that after Kalinga started unfurling its flag of independence, it followed a policy of hostility towards the Mauryan dynasty in Magadha. Dr. Bhandarkar supports Tripathy in this point and asserts that Kalinga had allied with the Chola and the Pandya power of the South to build a formidable opposition against the Mauryas. As a result when Bindusara attacked the Chola Empire down South, the joint opposition of the Cholas, Pandyas and Kalinga prompted him to retreat. In such circumstances, Kalinga became a threat to the Mauryan Empire. In due course the Kalinga Empire had strengthened their military power. So it became indispensable for Ashoka to conquer the Kalinga power in order to save his kingdom from the immediate threat. Moreover the material prosperity of Kalinga accentuated their trade relation with Malay, Java and Ceylon. Hence it was rather necessary for Ashoka to subjugate a rising power like Kalinga in order to retain his own supremacy. According to Romila Thapar, interpreter of modern history, the conquest of Kalinga was both strategically and economically important to Magadha.

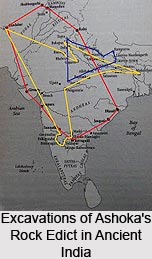

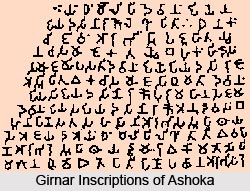

Apart from the accounts of the historical interpreters, the Rock Edict XIII of Ashoka served as the surviving authentic record of the Kalinga war. It is known from the inscriptions in the Rock Edict that Ashoka after a hard battle against the Kalinga power conquered the state. However the battle against Kalinga incurred a huge loss to the Kalinga Empire. Ashoka in his Rock edict inscribed the appalling story of carnage, death and deportation of the people in Kalinga. Numerous people had to suffer the reverses of war. However the historians in the later ages have pointed out that the story of losses as described in the rock edicts was simply an exaggerated detail. Bhandarkar had later suggested that perhaps the Cholas and the Pandyas joined the Kalinga War, which accounts for a huge loss of manpower. The conquest of the Kalinga Power rounded off the Mauryan Empire, which prepared the ground for the Maurya supremacy in South India. Ashoka appointed a prince of royal blood as the viceroy of the newly conquered territory of Kalinga.

The policy of conquest of Ashoka did not end satisfactorily. This is because the huge loss of lives during the Kalinga war satiated the lust of Ashoka for conquest or Digvijay. The consolidation of the Mauryan Empire was complete and there was no power in India, which could challenge the authority of the Mauryas. This is a point of controversy for the scholars that why Ashoka left his urge of conquest after the battle of Kalinga. However the explanation provided by the Buddhist text is quite satisfactory. The huge loss of lives during the Kalinga War filled his heart with deep remorse and in the repentant mood Ashoka embraced Buddhism. After becoming a Buddhist he inculcated Dhamma among all subjects. As a Buddhist he sent missionaries to the neighbouring lands in order to preach Buddhism. The policy of aggressive imperialism as initiated by the Mauryas was given a decent burial by Ashoka. The Kalinga conquest marked a new epoch, which turned the "Verighosa" (war drum) into "Dhammaghosa". The new era was the era of religious propaganda, toleration among various creeds and a benevolent concept of kingly duties.

The statement of the Buddhist text was refuted by the modern interpreters like Romila Thapar. According to her it was not the remorse of Ashoka, which prompted him to renounce the policy of conquest. The consolidation of the Kalinga Empire under the Mauryan authority resulted the Mauryas as the supreme power of entire India. The kingdoms of South India however proved friendly and loyal to him and accepted his missionaries. Hence Ashoka had to do nothing to win their allegiance. Rather Romila Thapar holds that Ashoka`s adoption of Dhamma and sending missionaries to the neighbouring areas was his own policy of conquest and annexation.

Bongard Levin, supports the theories established by Romila Thapar and pointed out that Ashoka was a shrewd diplomat. His adoption of Buddhism was just a change of his methods of foreign policy. According to Levin, in order to adapt himself to the new political situation Ashoka changed his foreign policy from one of force and aggression to non-violence. In doing this he at one end saved his kingdom from anymore alien aggressions and at the other hand owed the allegiance of the foreign rulers. According to Levin, Ashoka also changed his policy even in the native state. He prescribed uniform moral code to the subjects in order to retain his popularity among them. After the Kalinga war, Ashoka turned out to be a Buddhist just to change his tactics in his foreign policy. There was nothing of remorse of the reversals of the Kalinga War.

Bongard Levin, supports the theories established by Romila Thapar and pointed out that Ashoka was a shrewd diplomat. His adoption of Buddhism was just a change of his methods of foreign policy. According to Levin, in order to adapt himself to the new political situation Ashoka changed his foreign policy from one of force and aggression to non-violence. In doing this he at one end saved his kingdom from anymore alien aggressions and at the other hand owed the allegiance of the foreign rulers. According to Levin, Ashoka also changed his policy even in the native state. He prescribed uniform moral code to the subjects in order to retain his popularity among them. After the Kalinga war, Ashoka turned out to be a Buddhist just to change his tactics in his foreign policy. There was nothing of remorse of the reversals of the Kalinga War.

Koshambhi, another interpreter of the ancient history had pointed out that Ashoka`s conversion into Buddhism and adopting a non-violent foreign policy had nothing to do with the remorse of the Kalinga warfare. Rather Koshambhi provided an economic interpretation to the theory of Ashoka`s adoption of Buddhism that turned out to be non-violent. He interpreted that during that time there was an economic revival in India. The pastoral food gathering economy of the Vedic age was transformed into food producing economy. Overland trade had also become a source of economy in those days. Hence agriculture and trade had become two supplementary source of the Mauryan economy. Therefore Ashoka wanted to establish trade relations with the neighbouring countries. Therefore he turned out to be a resolute non-violent in his foreign policy so that he could establish a successful commercial relation with them.

Whatever the contradiction is, historians in the later periods have unanimously opined that the Kalinga war had turned Ashoka into Dharmasoka.